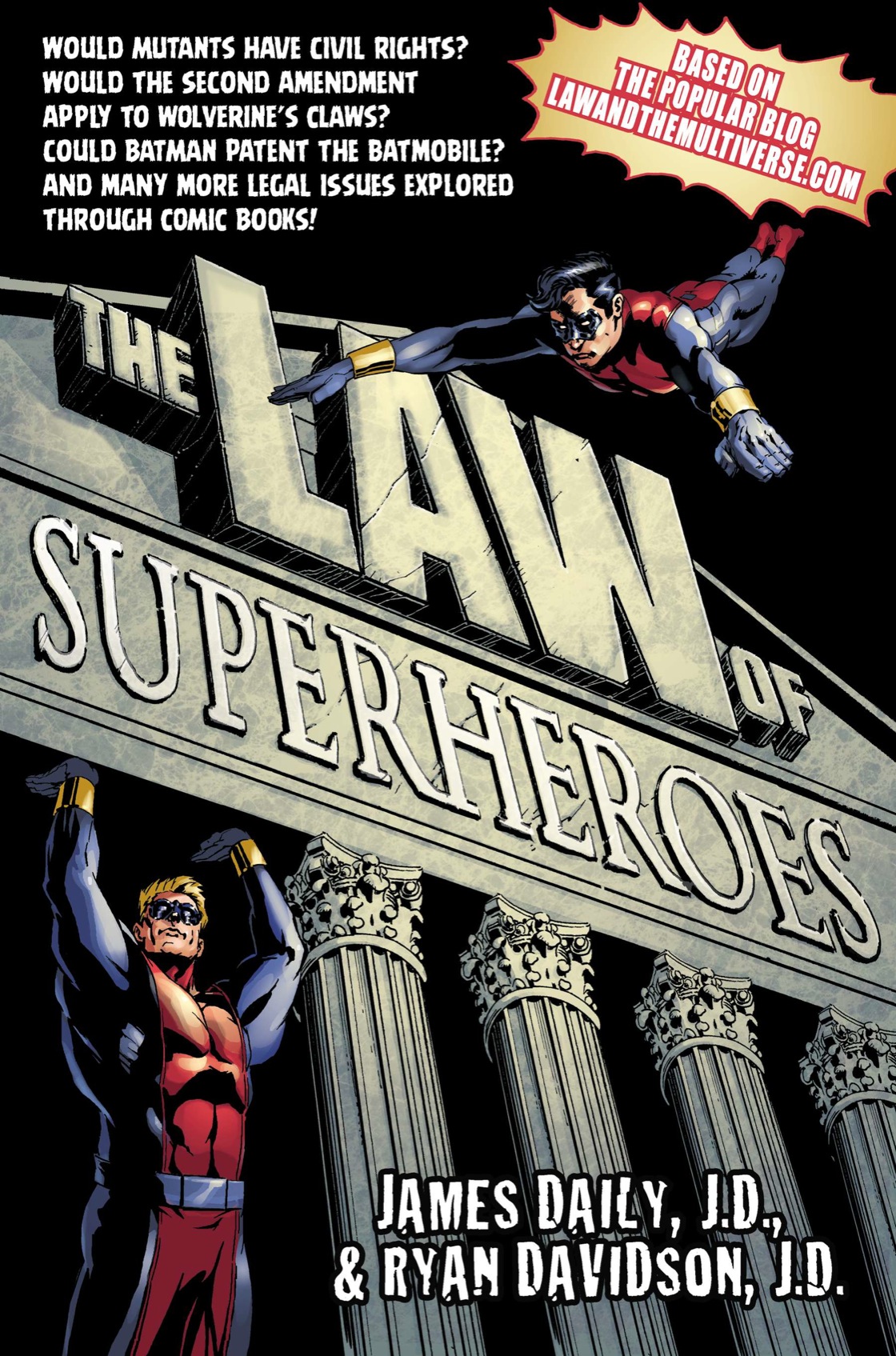

THE

LAW OF

SUPERHEROES

To Jennifer and Liesel

INTRODUCTION

Does Superman violate privacy laws when he uses his Xray vision? Does the Second Amendment protect Iron Mans suit? Is the Joker really legally insane? If youve ever wondered about any of these questionsor if they just sound awesomethen this is the book for you.

The Law of Superheroes grew out of the blog Law and the Multiverse, which applies real-world law and legal principles to comic book stories and characters. We, your coauthors, are both lawyers and comic book nerds, and this book blends those interests.

So why comic books? Well, for one thing, theyre both interesting and popular. The main problem with a lot of legal educational materials is that they are boring. Examples include such thrilling stories as A sells Blackacre to B, who then gives a life estate to C, and right there, before we even get to the law, the audience is asleep. But who doesnt like Batman? More to the point, who doesnt know who Batman is? Even someone who hasnt read any comic booksand you neednt have to in order to enjoy this bookwill probably know that Batmans alter ego is Bruce Wayne, billionaire industrialist. So rather than making up people who may not even have names, or using cases involving people youve never heard of, The Law of Superheroes uses characters you already know and love.

Second, comic book authors have been creating new stories for decades, which gives us an enormous supply of material. Action Comics, home of Superman, hit issue #904 in October 2011, part of an almost uninterrupted run since 1938. While this is the longest-running comic in history, there are plenty of others with hundreds and hundreds of issues. Comic book authors have created incredibly detailed worlds with their own histories, so detailed that the authors have felt the need to simplify things on a number of occasions. But continuity snarls aside, this means that comic book stories are ideal for this kind of analysis, because their longevity has given them the opportunity to cover a variety of legal situations that most other works simply dont reach. As a matter of fact, these situations often hold up remarkably well under legal scrutiny, which is a testament to the ingenuity of their authors, who have created such enormous yet cohesive and consistent worlds.

But most important, comic books are fun and invite good-natured overthinking. Like all comic book fans, we love wondering about how these richly detailed worlds would work in all sorts of ways, whether it be the physics of Supermans flight or his immigration status. Weve certainly had fun doing the research for this booktax-deductible comic books!and we hope to share that with you.

James E. Daily, J.D., and Ryan M. Davidson, J.D.

DISCLAIMER

This book discusses the hypothetical legal implications of fictional characters and situations and should not be relied upon in real-world legal situations. Nothing in this book constitutes legal advice or implies the existence of an attorney-client relationship with the authors. If you need legal advice or representation, consult a competent attorney in your jurisdiction.

The copyrighted DC Comics, Marvel, and Dark Horse illustrations in this book are reproduced for commentary, critical, and scholarly purposes. The copyright dates adjacent to the illustrations are the dates printed in the comics in which the illustrations were first published.

The terms superhero and supervillain are trademarks co-owned by Marvel Characters, Inc. and DC Comics, Inc. These terms are used throughout this book solely to refer descriptively to Marvel and DC characters. The copyright and trademark rights for the comic book characters and related logos and indicia mentioned throughout this book are the property of their respective owners.

LEGAL SOURCES AND CITATIONS

Throughout this book you will see references and citations to legal sources such as statutes and cases. Many of these primary sources are available for free online, and we encourage interested readers to seek them out. In order to assist the reader, we present an overview of the citation format used in this book and in most legal writing, the Bluebook.

Cases are generally cited in this form: [Case Name], [Volume Number] [Reporter] [Page Number] ([Court] [Year]). For example, United States v. Carroll Towing Co., 159 F.2d 169 (2d Cir. 1947) shows that the name of the case was United States v. Carroll Towing Co. and it was published in the 159th volume of the 2nd edition of the Federal Reporter beginning on page 169. We can also see that it was a decision of the Second Circuit Court of Appeals made in 1947.

When a particular portion of the opinion is cited, the specific page numbers will follow the first page number. For example, United States v. Carroll Towing Co., 159 F.2d 169, 17071 (2d Cir. 1947). Sometimes the court may be inferred from the reporter, as in United States Supreme Court cases, which are published in the United States Reports, abbreviated U.S. For example, Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1966). Many state supreme courts (e.g., California and New York) have similar official reports.

Unfortunately, citations to statutes (particularly state statutes) are less regular, but most of the statutory citations in this book are to the United States Code. The general form is [Title] [Statutory Code] [Section]. For example, 18 U.S.C. 1111 is Title 18 of the United States Code, Section 1111.

Most of the cases cited in this book may be found online via Google Scholar. State statutes are typically available on the website of the state legislature in question. For other kinds of citations and sources, see Professor Peter Martins guide, discussed in footnote 3 or the Bluebook itself. Readers with a further interest should contact their local law library or an attorney.

The Bluebook does not provide a citation format for comic books, so we have followed the citation format created by Britton Payne for the Fordham Intellectual Property, Media, and Entertainment Law Journal. and we think it captures all of the important information about a particular comic book. The general form of the citation is: Creative Contributors, Story Title, C OMIC B OOK T ITLE (V OLUME N UMBER ) [Issue Number] (Publisher Cover Date Month and Year). For brevity we typically only list the writer rather than the full panoply of creative contributors.

Consecutive citations to the same source are typically abbreviated as Id. This is Latin for idem, which means the same. To find the source referred to, just go back a few footnotes until you find a regular citation.

. T HE B LUEBOOK : A U NIFORM S YSTEM OF C ITATION (Columbia Law Review Assn et al. eds., 19th ed. 2010).

The current edition of the Bluebook, the nineteenth, is 511 pages long. As well-known federal circuit judge Richard Posner has said, the Bluebook is a monstrous growth, remote from the functional need for legal citation forms, that serves obscure needs of the legal culture and its student subculture.I am put in mind of Mr. Kurtzs dying words in Heart of Darkness