WILD SOCIALISM

Workers Councils in

Revolutionary Berlin,

191821

MARTIN COMACK

University Press of America, Inc.

Lanham Boulder New York Toronto Plymouth, UK

Copyright 2012 by

University Press of America, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard

Suite 200

Lanham, Maryland 20706

UPA Acquisitions Department (301) 459-3366

10 Thornbury Road

Plymouth PL6 7PP

United Kingdom

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

British Library Cataloging in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2012936684

ISBN: 978-0-7618-5903-1 (paperback : alk. paper)

eISBN: 978-0-7618-5904-8

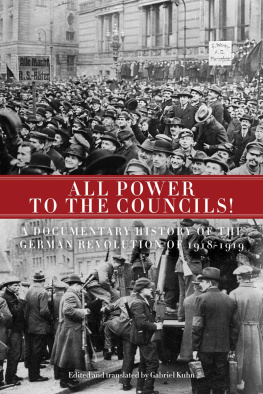

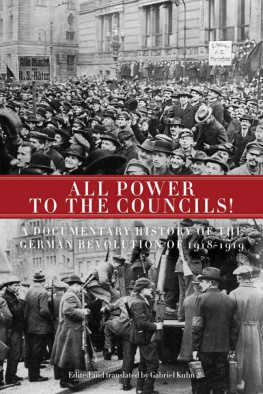

Cover: Berliners rally in support of the Congress of

Workers Councils convened there on December 16th, 1918

from Socialist Reproduction of London).

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992

Dedicated to the memory of

Augustin Souchy and his comrades

Preface

T his study examines the rise, development and decline of revolutionary councils of industrial workers in Berlin following the collapse of the German empire at the end of the first World War. Apparently spontaneous in origin, these organizations of rank and file workers spread throughout Germany and included mutinous soldiers and sailors. This popular movement was without precedent in either the theory or practice of the Social Democratic party and the trade unions allied to itthe traditional organs of working class political expression in Imperial Germany.

The workers councils were most highly developed and organized in the capital city of Berlin, within its particular industrial, political and cultural milieu. The Berlin Shop Stewards group provided a hard core of militant revolutionaries within the movement, many of whose adherents were more moderate or ambiguous in their views. Externally, the councilists faced a hostile Social Democratictrade union bureaucracy who characterized council rule as wilde Sozialismus, a reconstituted and repressive state power, and a revolutionary rival in the rise of German Bolshevism. In the following pages the experience of the Berlin councils will be considered as alternative institutions outside of traditional union, party and governmental structures.

Chapter 1

Introduction

B ack in the mid-1970s I had the pleasure and privilege of hosting Augustin Souchy as a house guest for several days. At that time Souchy was touring North America as the emissary of the revived Spanish National Confederation of Labor (Confederacion Nacional de TrabajoCNT). This revolutionary syndicalist union was engaged in reconstituting itself following the death of General Franco, and was anxious to establish contact with foreign supporters. Souchy himself had been a life-long anarcho-syndicalist, a participant in the German Revolution and the Spanish Civil War, he once had argued with Lenin over revolutionary principles. Now in his eighties, Souchy had spent much of his later life traveling the world as an educator, journalist and researcher on the issues and problems of workers control and self-management (Souchy 1992).

Despite his age and the stress of traveling, neither of which seemed to affect his vitality, Souchy was quite forthcoming in taking the time to describe his various experiences and to present his thoughts on political and social topics. I became particularly interested in his discussion of the workers councils in Germany and their role as an alternative movement to both Social Democracy and Bolshevism.

Around this same period, I also had the opportunity of attending talks by Paul Mattick, another German who, like Souchy, had been active in revolutionary days in Berlin. Mattick had been a member of the anti-Bolshevik Communist Workers Party (Kommunistische Arbeiter-Partei DeutschlandsKAPD). In exile in America, he had made his living as a machinist, and had become a theoretician of council communisma liberarian branch of Marxist thought.

The similarity in experiences and the conclusions drawn from them by these two veteran revolutionaries seemed to be of greater significance than any theoretical differences that might have separated them. In any case, since then I have maintained an abiding interest in the phenomenon of independent workers councils, particularly in the German contextone of the earliest attempts at achieving workers autonomy and control of production in the twentieth century. I hope that this paper will serve as a contribution to the study and understanding of this subject.

Chapter 2

Berlin

R egarded as one of the newer capitals of Europe, Berlin owes its modern facade largely to its rapid rate of growth in the late nineteenth century. Berlins expansion in that period has been compared to that of North American cities like Chicago (Masur 1970: 132). But by the turn of the twentieth century, Berlin was at least the equal of her European counterparts not only in size, but in quality of urban life and cultural amenities. The metropolis had by then made the transition from what the German language defines as a great cityGrosstadt, to that of a world-class cityWeltstadt. With some two million inhabitants in 1900, Berlin would double in population within twenty years with the incorporation of its industrial suburbs into the municipality and expand in area to 90 square kilometers, the largest city in Europe after London (Watt 1968: 259; Gill 1993: 34). Given a national population of sixty million, approximately one of every fifteen Germans resided in Berlin or its immediate environs by the early years of the twentieth century (Peukert 1992: 7).

The center of the city was the site of spacious squares and parks, with affluent residential areas set off by massive government buildings and military headquarters (Diesel 1931: 101-102; Berlin 1985). Besides a large municipal bureaucracy, in its capacity as capital of the state of Prussia, Berlin also housed provincial administrative offices. But most notably, Berlin was the seat of government of the German Empire. This Greater Germany of Kaiser Wilhelm II stretched from the French border eastward to the frontiers of Russian Poland, from the Baltic south to the Alps, with colonies, spheres of influence, and commercial and strategic interests throughout Asia, Africa and the Western Hemisphere. The complex, sometimes overlapping jurisdictions of imperial, provincial and local administrations required a host of civil servants and public officials to staff the agencies and ministries of the various governmental units. Not least, imperial Berlin was the command center for the most powerful and efficient military establishment in Europe and the world. In one sense, as a contemporary commentator noted, the citys natural expression was in large measure the office and the barrack (Diesel 1931: 100).

For Berlin, as for the German nation, the basis of imperial grandeur and military power lay in Germanys recent development from a mostly agrarian to an industrial, urbanized society. Like Chicago, Berlin was the center of a national transport systemby the twentieth century an extensive network of railways and canals (Diesel 1931: 52-54). The nationalized railroad system proved to be a motor of Berlins accelerated industrial growth. Locomotive and freightcar repair shops and machine building enterprises became the basis for a giant metallurgical industryfrom small workshops to large factory complexes. At the Berlin Industrial Exposition of 1879, engineers of the Siemens company demonstrated the first electric tramway and launched a new branch of industry. Siemens, along with the Allgemeine Elektrizitat Gesellschaft (AEG) made Berlin the center for the manufacture of electrical machines and components, resulting in the electrification of the entire German economy (Landes 1969: 287).

Next page

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992