Table of Contents

Praise for The First World War

The Great War of 1914 1918 is increasingly and accurately regarded as the defining event of the twentieth century. This is quite simply the best short history of the war in print. Strachan provides a history of the war as a global conflict, waged for fundamental issues that continue to shape our values, and the way we see the world. The governments, the societies, and the people who sacrificed on scales barely imaginable today were not deluded players on a stage of shadows. Strachan has emerged as the master of us all who write of war in English.

Dennis Showalter

This is a powerful and highly readable account of the determining event of the twentieth century. The many photographs are outstanding.

Paul Johnson

What Strachan offers is history as only the professional can do it, and rarely enough even then. Every intricacy, political, military, and diplomatic, of the conflict is open for inspection.

Adam Gopnik, The New Yorker

A marvel of synthesis... This serious, compact survey of the wars history stands out as the most well-informed, accessible work available.

Los Angeles Times

Splendid... the prose is so clear that the authors fellow academics may revoke his numerous honors. The Washington Post

This is likely to be the most indispensable one-volume work on the subject since John Keegans First World War .

Publishers Weekly

A well-conceived and lucidly written survey of the twentieth centurys first great bloodletting, with close attention to little-known episodes in and preceding the conflict... The best single-volume treatment of the conflict in recent years. Kirkus Reviews

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Hew Strachan is the Chichele Professor of the History of War and a fellow of All Souls College, Oxford University. The editor of The Oxford History of the First World War , he is writing a three-volume history of the First World War, the first volume of which was published in 2001 to wide acclaim. He lives in Scotland.

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A.

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario,

Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephens Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell,

Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park,

New Delhi - 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0745,

Auckland, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank,

Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices:

80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

First published in the United States of America by Viking Penguin,

a member of Penguin Group (USA), Inc. 2004

Published in Penguin Books 2005

10 9

Copyright Hew Strachan, 2003

All rights reserved

eISBN : 978-1-101-15341-3

1. World War, 1914 1918. I. Title.

D521.S86 2004

640.3 dc22 2003062191

The scanning, uploading and distribution of this book via the Internet or via any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal and punishable by law. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the authors rights is appreciated.

http://us.penguingroup.com

For Pamela and Mungo

Who may not have lived through the First World War but have had to live with it

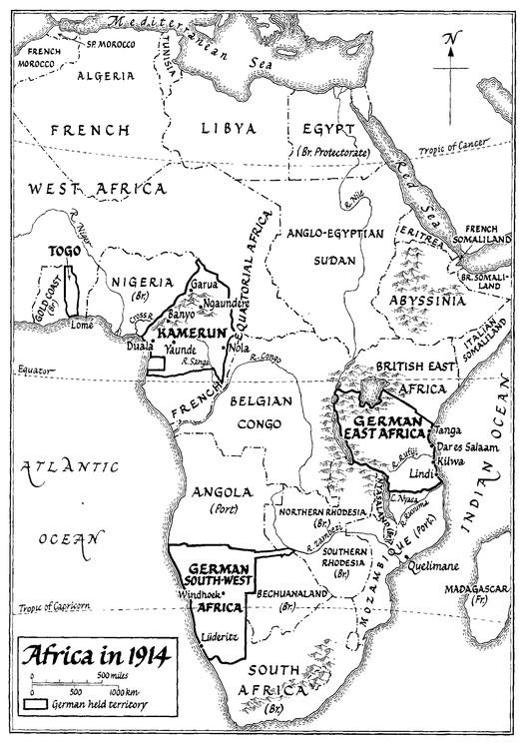

INTRODUCTION

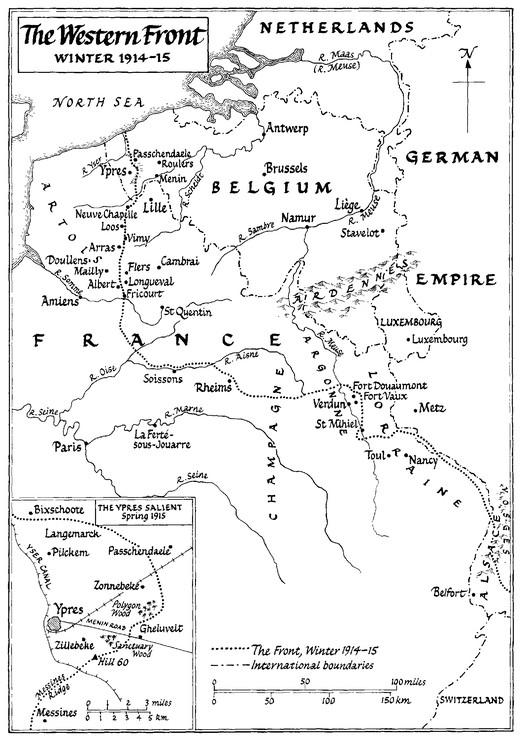

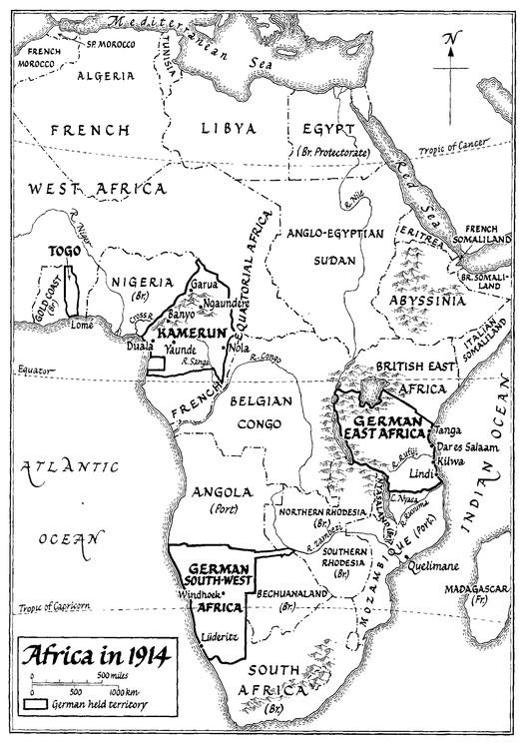

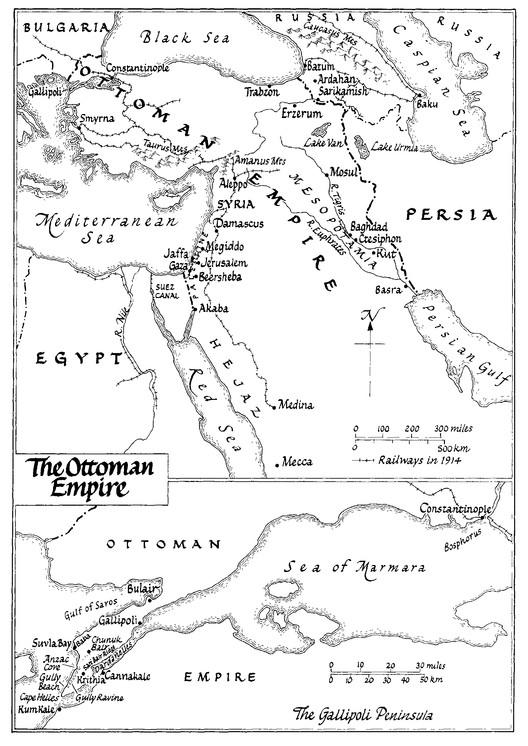

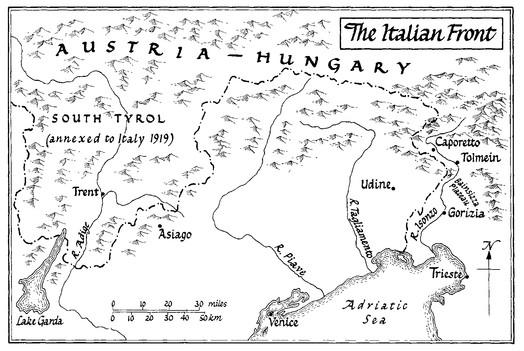

I n Britain popular interest in the First World War runs at levels that surprise almost all other nations, with the possible exception of France. The conclud ing series of Blackadder , the enormously successful BBC satirization of the history of England, saw its heroes in the trenches. Its humour assumed an audience familiar with chteau-bound generals, goofy staff officers and cynical but long-suffering infantrymen. The notion that British soldiers were lions led by donkeys continues to provoke a debate that has not lost its passion, even if it is now devoid of originality. For a war that was global, it is a massively restricted vision: a conflict measured in yards of mud along a narrow corridor of Flanders and northern France. It knows nothing of the Italian Alps or of the Masurian lakes; it bypasses the continents of Africa and Asia; and it forgets the wars other participants diplomats and sailors, politicians and labourers, women and children.

Casualty levels do not provide a satisfactory explanation for such insularity. British deaths in the First World War may have exceeded those of the Second, and Britain is unusual, if not unique, in this respect. The reverse is true for Germany and Russia, as it is for the United States. However, even losses of three-quarters of a million proved to be little more than a blip in demographic terms. The influenza epidemic that swept from Asia through Europe and America in 1918 19 killed more people than the First World War. By the mid- 1920s the population of Britain, like those of other belligerents, was recovering to its pre-war levels. In the crude statistics of rates of marriage and reproduction there was no lost generation.

But the British, and particularly the better educated classes, believed there was. The legacy of literature, and its effects on the shaping of memory, have proved far more influential than economic or political realities. In 1961, Benjamin Britten incorporated nine poems by Wilfred Owen in his War Requiem, which he dedicated to the memory of four friends who had been killed in 1939 45. The work was first performed at the consecration of the Coventry Cathedral in 1962. The old cathedral was a casualty of the Second World War, not the First, but Britten was following an established pattern in conflating the commemoration of the two wars. Armistice Day for the First World War, 11 November 1918, and the act of remembrance on the nearest Sunday to it, was appropriated to honour the dead of 1939-45. Today Remembrance Sunday embraces not only every subsequent war in which Britain has been engaged but also more general reflections on war itself, and on its cost in blood and suffering. The annual service at the Cenotaph in Whitehall is therefore deeply paradoxical. A ceremony weighted with nationalism, attended by the Queen and orchestrated as a military parade, bemoans wars fought in the nations name. It cuts away wars triumphalism, and in the process seems to question the necessity of the very conflicts in which those it commemorates met their deaths.

Next page