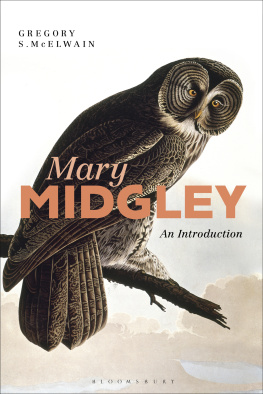

Frog Pond Philosophy

FROG POND PHILOSOPHY

Essays on the Relationship between Humans and Nature

STRACHAN DONNELLEY

Edited by

Ceara Donnelley and Bruce Jennings

Foreword by

Frederick L. Kirschenmann

Due to variations in the technical specifications of different electronic reading devices, some elements of this ebook may not appear as they do in the print edition. Readers are encouraged to experiment with user settings for optimum results.

Copyright 2018 by The University Press of Kentucky

Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth,

serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University.

All rights reserved.

Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky

663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008

www.kentuckypress.com

Cataloging-in-Publication data is available from the Library of Congress

ISBN 978-0-8131-6727-5 (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-8131-6728-2 (pdf)

ISBN 978-0-8131-6729-9 (epub)

This book is printed on acid-free paper meeting

the requirements of the American National Standard

for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America.

| Member of the Association of

American University Presses |

To Vivian

Contents

by Frederick L. Kirschenmann

Foreword

Strachan Donnelleys Frog Pond Philosophy is an extremely important and timely book. We, especially in the industrial world, still seem to be locked into a culture that is focused on instant gratification and the notion that the most efficient way to achieve that objective is through the mechanistic, nature-dominating philosophy proposed by Ren Descartes, Isaac Newton, and others, and it is a culture that threatens the very health of the planet and the human species that is an integral part of it. As Donnelley points out so eloquently, there have been other thinkers in our history who have advanced an alternative view, including Alfred North Whitehead, Charles Darwin, and Aldo Leopold, but many of our academics have featured their perspectives only as rational academic exercises, which have failed to energize us to embrace the existential reality that we humans are part of nature and all of its emergent properties. We are still focused on how to use nature more efficiently to achieve our distorted objectives, and so we are still a long way from recognizing Leopolds vision that we need to move beyond the notion that the land is a commodity belonging to us rather than a community to which we belong.

Donnelley also used creative analogies to help us make the transition to an engagement philosophy that can move us toward a more alive embrace of nature as an engaged experience in which we are an active part. Among many other analogies, he used music to show that life is a complex interaction, constantly evolving, of the composer; the musical score; the conductor; the orchestra and the chorus; the soloists; the members of the audience (each with different musical ears and personal concerns); the orchestral hall with its acoustics; the wider world in its present historical and cultural moment; and no doubt more (see ). Given this complex and dynamic context, we have no choice but to become personally engaged. Objective, disengaged academic exploration will not do.

This evolving experience of life in nature gives us a radical and extremely important perspective that must become a part of our new culture if we are to evolve with a life experience that has the potential to engage us in a fruitful and sustainable life and world. I hope that this book will be read by academic professionals and business leaders, as well as by ordinary citizens, to start us on a journey toward a new culture that will be essential to our existence within nature and to a quality of life that currently escapes us.

Frederick L. Kirschenmann

Introduction

Editors note: At the time of his death in 2008, Strachan Donnelley had organized a number of his published and unpublished papers for publication as a book and had written this introduction. He did not finalize the sequence of chapters as presented here himself, so this introduction does not present an overview. It does, however, offer an important statement of the intent and the spirit in which Strachan hoped his work would be read. For more information, see the Editors Afterword.

I have always believed in truth in advertising. I see no reason to stop now. It will serve me to introduce this collection of essays and articles.

Early last fall, I was diagnosed with gastric cancer, which is inexorably working its dark magic. It is time for me to get my many-roomed house in order, including bringing together these several pieces written over several years of professional philosophic and civic life.

This inconvenient truth and what I like to call yapping puppies (the cancer), now having bolted from the kennel, push me in a direction that I want to go in any case. I have long had a core personal and professional passion for exploring nature: its innumerable landscapes, values, and goodness; the nature of earthly ecosystemic life and our own dynamic and historical implications in this incredible realm of natural existence; finally, what we can do, culturally and practically (civically), to help secure and enhance the future of both humans and nature. Humans dwell within an ultimately valuable and good nature. And nature, both abroad and internally within our living, mindful bodies, which include our individual selves, is in us personally, culturally, civically, spiritually, and more. As Alfred North Whitehead would say, humans and nature are mutually and internally in each other (mutually immanent). We together constitute nature alive. On some level, we all know this to be true, despite countervailing cultural and religious habits to the contrary.

The rub is not only the ingrained cultural habits that bedevil an adequate understanding of ourselves and our world. Despite our core, experientially well-founded conviction, not easily assailable, that we dwell within nature, we do not fully understand or know how we dwell within nature alive. Most likely, we never will. Ignoramus: we are ignorant.

What has this stubborn fact meant for me? At my best, I have lived the life of an explorer, most pointedly as a thinker: before college; as an undergraduate and graduate student; as a professional thinker (Hannah Arendts mocking term for employed philosophers) in teaching institutions; at the Hastings Center (an independent bioethics organization); and presently at the Center for Humans and Nature, which I helped to found in 2003 and still direct. Unsurprisingly, the mission of the center is to explore, articulate, and promote ethical and civic responsibilities for human communities and nature. We are still on the road.

Next page