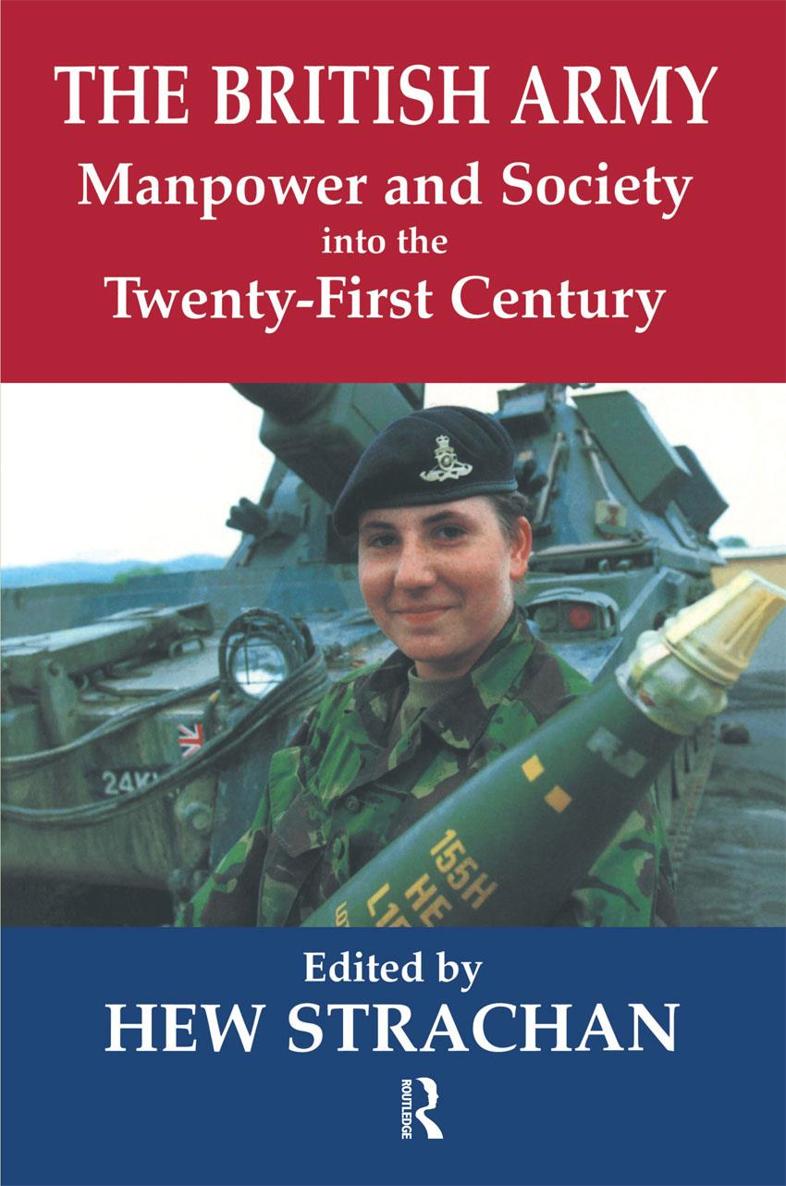

THE BRITISH ARMY, MANPOWER AND SOCIETY INTO THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY

THE BRITISH ARMY, MANPOWER AND SOCIETY

INTO THE

TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY

Edited by

HEW STRACHAN

University of Glasgow

First published 2000 by Frank Cass Publishers

Published 2021 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

605 Third Avenue, New York, NY 1001 7

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa busliness

Copyright of collection 2000 Taylor & Francis.

Copyright of chapters 2000 contributors

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

The British Army, manpower and society into the twenty-first century

1. Great Britain. Army 2. Women and the military Great Britain 3. Sociology, Military Great Britain

I. Strachan, Hew

355 .00941

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

The British Army, manpower and society into the twenty-first century / edited by Hew Strachan

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-7146-5005-6 (cloth) ISBN 0-7146-8069-9 (paper)

1. Great Britain. Army Recruiting, enlistment, etc. 2. Sociology, Military Great Britain. I. Strachan, Hew.

UB335. G7 .B75 1999 306.270941 dc21 | 99-045938 |

Typeset by Regent Typesetting, London

ISBN 13: 978-0-7146-8069-9 (pbk)

ISBN 13: 978-0-7146-5005-0 (hbk)

ISBN 13: 978-1-315-03965-7 (ebk)

DOI: 10.4324/9781315039657

Contents

Hew Strachan

Hew Strachan

Jeremy A. Crang

S.J. Ball

John Baynes

Antony Beevor

Reggie von Zugbach de Sugg and Mohammed Ishaq

Christopher Jessup

Peter Bracken

Stephen Deakin

Stuart Crawford

Benjamin Foss

Christopher Dandeker

Sebastian Roberts

Iain Torrance

Alan Hawley

Charles Kirke

Patrick Mileham

The debate about how far an army should reflect the values and standards of society remains wide open. On one side, there are those who believe that the physical and psychological demands on a soldier in battle are enduring and unchanging and that these dictate how a soldier should be trained and behave in peacetime. On the other side, there are those who believe that an army should closely reflect the culture of the society from which it draws its membership and that to remain an isolated, backward-looking organisation will ultimately render an army irrelevant to the needs of the nation.

As Sebastian Roberts points out in his thoughtful article, fighting power comes from three components: conceptual, physical and moral. During the past 50 years of Cold War soldiering, the British Army, along with other NATO armies, has almost exclusively pursued the physical and conceptual components of fighting power. The physical component clearly needed to be emphasised during the period of East/West confrontation, as this was the best means of demonstrating the technical superiority of NATO over the Warsaw Pact. The second component, namely the conceptual, allowed the physical means at the disposal of NATO to be put to its best deterrent effect. All this successfully resulted in a NATO victory against the Warsaw Pact. However, it was a victory accomplished during a war of deterrence in which no shots were fired, and no one was actually exposed to the extreme violence and chaos of war. But in war it is often the moral component that predominates, and history is littered with examples of armies which were both physically and conceptually superior to their opponents, but who were nevertheless decisively defeated by armies which attached a greater importance to the moral component of fighting power than they did.

NATOs failure to pay sufficient attention to the moral component of fighting power during the Cold War has had a disastrous effect on its employability in time of war. The reluctance of NATO to deploy combat troops in Kosovo in March 1999 stemmed not just from a political reluctance to accept casualties but, more importantly, came also from a recognition that the alliance lacked sufficient troops capable of fighting in a way that would ensure victory against the Serbs. For a ground war in Kosovo would have involved the same sort of close combat that was fought by the men of the British 14th Army in Burma during the Second World War, where every bunker had to be destroyed, every hilltop taken, and every village cleared of the enemy. The Japanese could never have been defeated by bombing or from a remote distance by precision-guided munitions. Over half a century later, the Nato bombing campaign in Kosovo demonstrated the same clear lesson for the Serb army emerged largely unscathed after one of the most intensive bombing campaigns in history. Such battles can only be won by hard, aggressive soldiers capable of prolonged fighting with the rifle, bayonet and machine gun.

Fighting is an attitude of mind, and the willingness to kill and be killed comes from a blend of faith, trust in the leadership, harsh discipline and compulsion. It is this, combined with pride in the unit and comradeship, that creates the military ethos that sustains soldiers in time of war. In the British Army, the moral component of fighting power is founded on a distinct military ethos, deriving from the fundamental belief that soldiers are not merely civilians in uniform but form a distinctive group within society: no other group is required to kill other human beings or deliberately sacrifice their lives for the nation.

Troops who have become accustomed to a peacetime regime based on civilian practices involving restricted working hours, health and safety regulations, or the right of appeal to industrial tribunals outside the chain of command, cannot be expected to make the necessary physical or mental transition in time of war. Nor do modern forms of conflict based on technology render the fighting qualities of the individual soldier or small unit on the battlefield irrelevant. Indeed, conflict in the twenty-first century is more likely to involve peacekeeping and peace-enforcement operations than general war, and to perform successfully in the brutal and chaotic circumstances that prevail in these forms of modern conflict, a soldier will require all the disciplines and psychological preparedness of general war. Soldiers will also need to accept a greater moral responsibility and understanding of human rights than in general war, and the traditional discipline and standards of the British Army prepare them particularly well for these new forms of humanitarian war.

Today, the military ethos of the British Army, on which the moral component of fighting power depends, is not merely suffering from past neglect, it is being threatened by a mixture of cultural change within society, and by new national and international legislation. The importance attached in modern society to the pursuit of individual and minority-group interests even when the consequences of this logic are damaging to the interests of the whole has resulted in radical changes to the military ethos and disciplinary relationships within the armed forces. If an army is to perform successfully in war, its underlying ethos must, I firmly believe, be different from that of civilian society, whose beliefs tend to be faddish and certainly are not derived from the necessities of war. This does not mean that it needs to isolate itself from society or adopt a holier-than-thou attitude. Nor will an army with an ethos that is different from that of society necessarily find it difficult to recruit soldiers many people in civilian life welcome and admire military standards, as surveys continually demonstrate. Undoubtedly, as memory of military service fades, the British Army does need to explain its purpose more clearly to the civilian community, and it has to spend more time in preparing people physically and mentally for military life. Thus the difficulty that the British Army has today in manning to its full established strength is not caused by low recruitment, but by poor retention. Political correctness and overstretch make poor retention officers.