Published by

SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION SCHOLARLY PRESS

P.O. Box 37012, MRC 957

Washington, D.C. 20013-7012

www.scholarlypress.si.edu

Compilation copyright 2015 by Smithsonian Institution

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

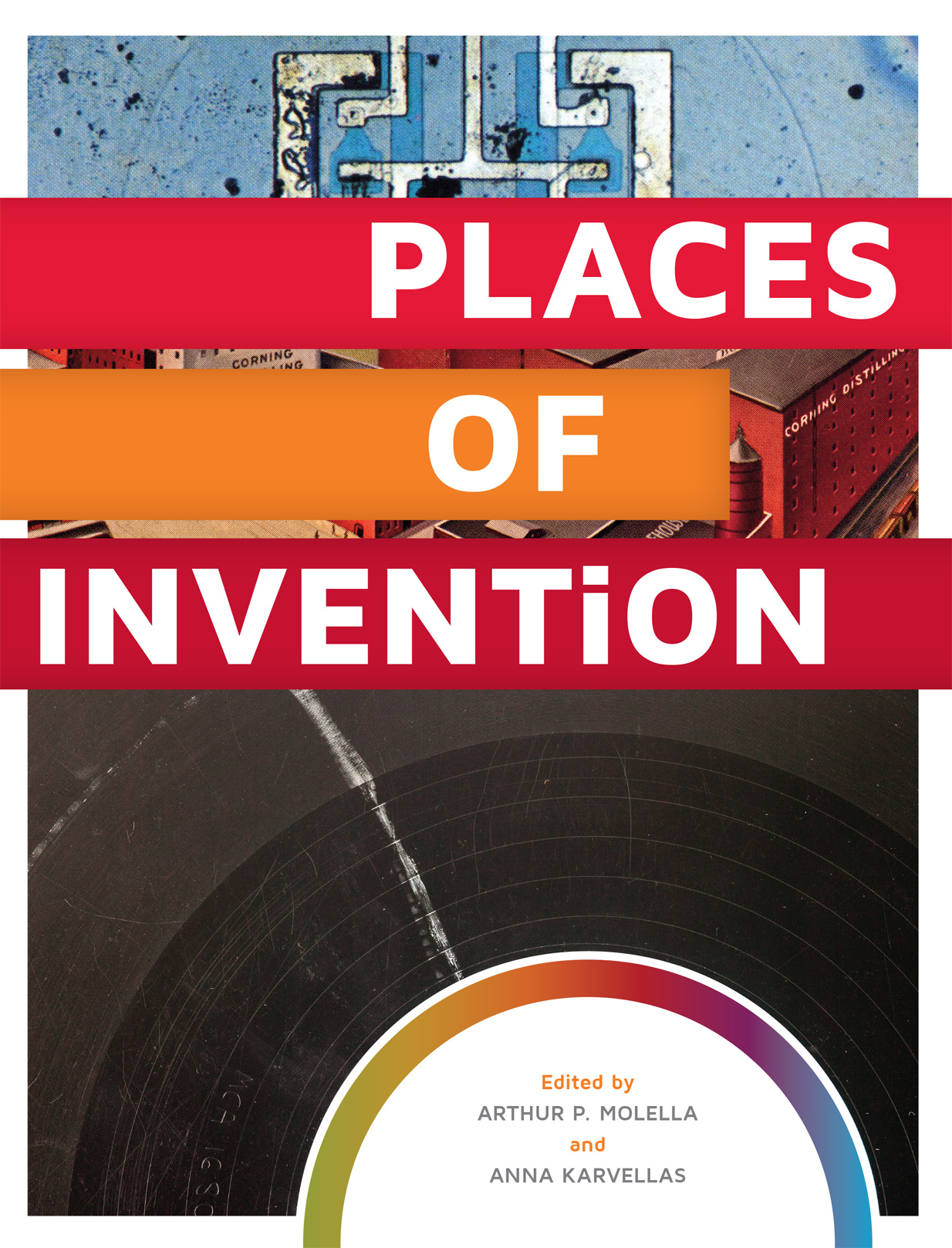

Front cover images: (top) detail of first production planar IC, 1960, Fairchild Semiconductor. Courtesy of the Computer History Museum, Mountain View, California, Image #500004791; (middle) distillery of Corning and Company, Peoria, Illinois, about 18801919, Peoria Historical Society Collection, Bradley University Library; (bottom) detail of Bustin Loose record by Chuck Brown and the Soul Searchers, 1978, with grease marks made by Grandmaster Flash, 2014 Smithsonian Institution; photo by Richard Strauss. Courtesy of National Museum of American History.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data:

Places of Invention (2015 : Washington, D.C.)

Places of invention / edited by Arthur P. Molella and Anna Karvellas.

pages cm

Accompanies the Places of Invention Exhibition at Smithsonians National Museum of American History, 2015.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-935623-68-7 (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-935623-69-4 (ebook) 1. InventionsUnited StatesHistoryExhibitions. 2. Industrial productivity centersUnited StatesExhibitions. 3. Technology and stateUnited StatesExhibitions. 4. Industrial locationUnited StatesExhibitions. 5. Diffusion of innovationsExhibitions. I. Molella, Arthur P., 1944 editor. II. Karvellas, Anna, editor. III. Title.

T21.P57 2015

609.73dc23

2014042368

v3.1

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

Robert E. Simon Jr.

MUSEUM DIRECTORS NOTE

John L. Gray

INTRODUCTION

Arthur P. Molella and Anna Karvellas

SILICON VALLEY (1970s80s)

Eric S. Hintz | Suburban Garage Hackers + Lab Researchers = Personal Computing

BRONX (1970s)

Laurel Fritzsch | Neighborhood Streets Create New Beats

Anna Karvellas | Dispatch from Greater Seattle | The Rise of Seattles Gaming Industry (1980sToday)

MEDICAL ALLEY (1950s)

Monica M. Smith | Tight-Knit Community of Tinkerers Keeps Hearts Ticking

HARTFORD (Late 1800s)

Eric S. Hintz | Factory Town Puts the Pieces Together in Explosive New Ways

Anna Karvellas | Dispatch from Peoria | Mass Production of Penicillin (1940s)

HOLLYWOOD (1930s)

Joyce Bedi | Follow the Rainbow to the Movies Golden Age

FORT COLLINS (2010s)

Joyce Bedi | Campus and City Combine Their Energies for a Greener Planet

Anna Karvellas | Dispatch from Pittsburgh | Jazz Innovation (1920s70s)

WHATS NEXT? MUSEUMS AND INNOVATION

Lorraine McConaghy

FOREWORD

This book and its companion exhibition explore the idea that most invention does not spring spontaneously from a single brain, but is fostered by the fertile soil of a particular place. Such places of invention can be identified by their geography, society, and creative culture. They make the most of natural and manmade resources and provide shared spaces for the exchange of ideas. The invention itself can be an object, such as a machine or device, or even a formula or a melody. It also can be a new or improved way of doing things, for instance, planning a new community.

My connection with the new town of Reston started in 1961 with the acquisition of 6,750 acres of land in Virginia located between Washington, D.C., and what is now Washington Dulles International Airport. I was involved in preparing its original plan and social programs and assembled a wonderful team of planners, architects, engineers, builders, realtors, educators, and sociologists to implement the program and bring it to market. At the time, we could not predict the rise of the Dulles Technology Corridor, but studies did forecast the substantial growth that would come to the Washington metropolitan region. We knew that Restons proximity to Dulles Airport and the planned Dulles Access Road would provide key links between Reston, Washington, and the world that would heighten its appeal to prospective residents.

We wanted to do more for these residents than create another bedroom community. We wanted to create a place where people could live, work, and playto create a walkable community with shared open spaces where people of all ages and backgrounds would gather. In 1965, the laudatory reception following the opening ceremonies, astonishingly international as well as national, indicated that the Reston team had, indeed, produced a new and improved way of building a community in the United States. In our plans were many of the concepts examined in this book; concepts which are still part of the ongoing discussion about the creation of innovation districts.

It has been said that Restons influence on urban planning extends to many countries. As an indication of this, visitations from abroad started up almost immediately. In 1966, a Japanese crew arrived with a reporter, a translator, and a sound truck. Since then, a steady flow of visitors has continued. In the last five years signatures from fifteen different countries coming from five continents have appeared in the Reston Museums guest book.

Of course, I am always happy to express the debt that Restons original plan owes to my early influences:

Separation of pedestrians from vehicles (Reston has nineteen underpasses and one overpass). The use of underpasses and overpasses can be traced to Leonardo da Vinci, who incorporated these elements into his designs for the suburbs of Milan, at the request of the Duke of Milan. I also was inspired by their use in Radburn, New Jersey, a planned community in which my father was involved.

Lake Anne Plaza, the focal point for Restons first arrivals, can be traced to plazas in most continents. I was particularly inspired by the plazas in Italian hill towns.

The fifteen-story Heron House was inspired by the high-rise in Tapiola, Finland, outside of Helsinki. Heron House was built to create a here here in the Virginia boonies for Lake Anne Village Center. Without Heron House, Restons debut might have suffered the same criticism that Gertrude Stein tagged to Oakland, California, complaining that there was no there there.

Sculpture for the delight of grown people and their offspring was a part of Restons very beginnings. It was inspired by mature urban settings around the world.

The idea for amenities such as walking-bike trails, a community center, ball fields, a swimming pool, and tennis courts came from Radburn. This concept was much ahead of its time.

Lake Annes fountain is a miniature of Lake Genevas fountain.

Atop Lake Anne Plazas stores, townhouses had front yards with trees, shrubs, flowers, and grass. These townhouses were inspired by those in San Franciscos Embarcadero.

I have been prone to say that there is nothing new in Reston except, possibly, the collection of features that I had admired in my travels and personal experiences. Perhaps this collection, motivated by a desire to build COMMUNITY and to create another way of living, is itself an invention designed to foster the invention of others. Now more than 50 years old, Restons story shares many characteristics with the places of invention explored in this book. One hopes that these stories inspire readers to make their own collections and think about ways to create places of invention where they live.