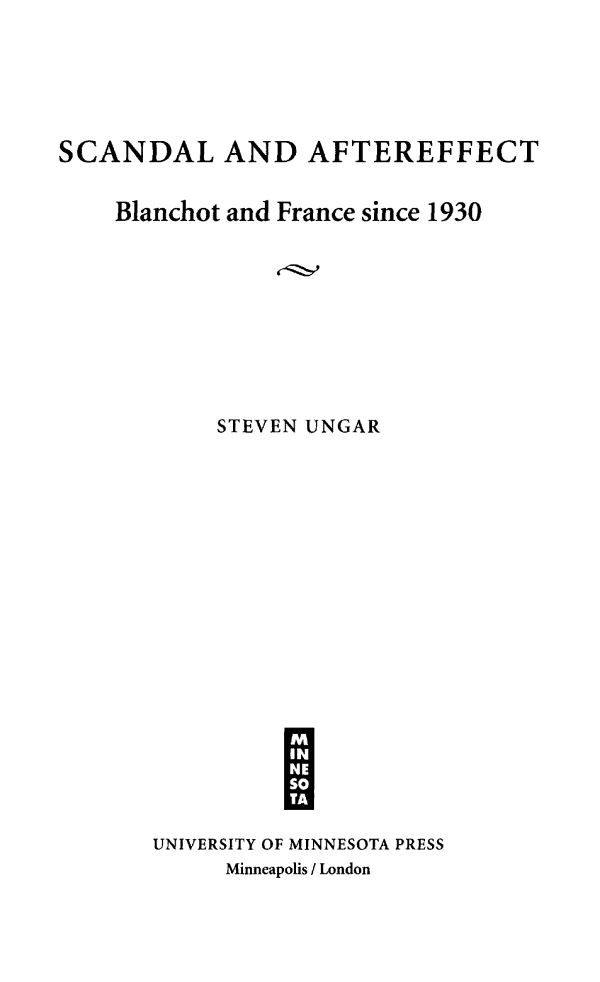

Steven Ungar - Scandal and Aftereffect: Blanchot and France Since 1930

Here you can read online Steven Ungar - Scandal and Aftereffect: Blanchot and France Since 1930 full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. publisher: University of Minnesota Press, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Scandal and Aftereffect: Blanchot and France Since 1930

- Author:

- Publisher:University of Minnesota Press

- Genre:

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Scandal and Aftereffect: Blanchot and France Since 1930: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Scandal and Aftereffect: Blanchot and France Since 1930" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Scandal and Aftereffect: Blanchot and France Since 1930 — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Scandal and Aftereffect: Blanchot and France Since 1930" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

I dedicate this book to the past and for the future: to the memory of my father's mother, Anna Lowy Ungar (1893-1944), who died at Auschwitz, and to my daughters, Anna and Shira.

There is an unavoidable necessity for the reader, who naturally comes to the essay from without, to refrain at first and for a long time from perceiving and interpreting the facts of the case in terms of the reticent domain that is the source of what has to be thought. For the author himself, however, there remains the pressing need of speaking each time in the language most opportune for each of the various stations on his way.

Martin Heidegger,

"The Origin of the Work of Art"

One must in the end speak dangerously and dangerously remain silent in the very act of breaking this silence.

Maurice Blanchot

(from a letter to Emmanuel Levinas, February 11,1980)

Acknowledgments

One never ends with the book one starts to write because one never writes alone. Friends and colleagues have challenged me through their efforts and words to see things I never foresaw when this project first took shape. At the University of Iowa, I thank my colleagues (past and present) Dudley Andrew, Paul Greenough, Allan Megill, Kathleen Newman, Herman Rapaport, Rosemarie Scullion, Alan Spitzer, and Abby Zanger for dialogue and critique. Since 1985, Jay Semel and Lorna Olson have provided me with space at the University of Iowa Center for Advanced Studies in an environment uniquely conducive to long-term research. Out on the road from Los Angeles to New Haven and from Urbino to Warwick, I had the good fortune to be invited by Dana Polan, Gayatri Spivak, Lynn Higgins, Hugh Silverman, Francesco Casetti, Shuhsi Kao, Geoffrey Waite, Philip Lewis, Ora Avni, Sydney Levy, Carolyn Gill, Mary Lydon, and Christopher Thompson to present sections of this work in progress. The readings of my manuscript that Denis Hollier, Ann Smock, and Reda Bensma'ia provided to the University of Minnesota Press were incisive and illuminating. In Paris, conversations with Margaret and Daniel Wronecki kept things in a French perspective. Closer to home, I recall with gratitude the participation of Ben Attias, Joanna Klink, Laura Rozen, and Elliott Van Skike in my 1990 seminar on Bataille and Blanchot. Thanks also to David Eick for help under pressure with the index. Finally, I am grateful for the support that Walter Strauss, Michael Holland, and Tom Conley provided at critical stages along the way. As with so much else that I value in my life, Robin Ungar has accompanied this project from start to finish.

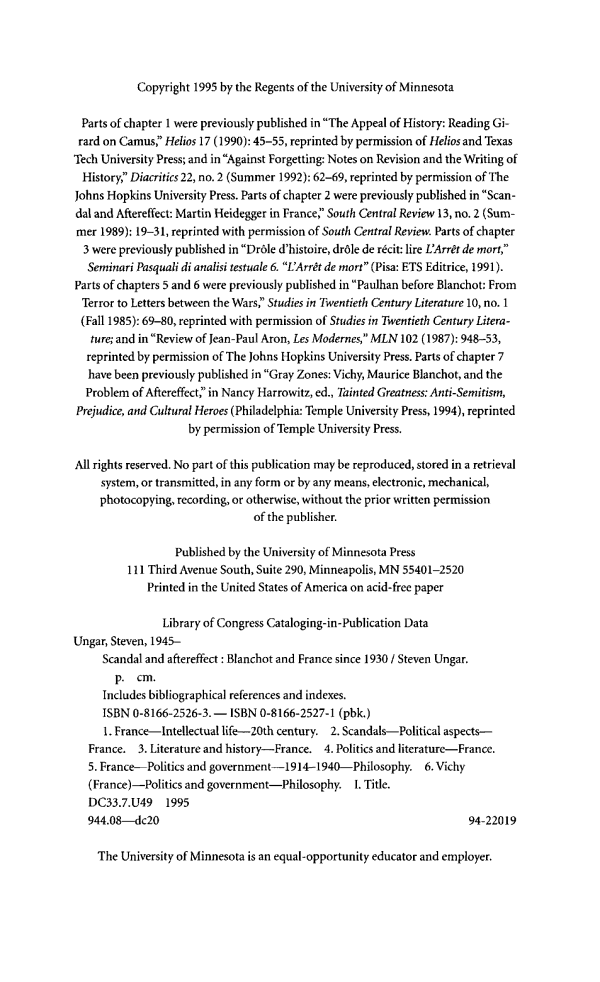

This book contains revisions of previously published materials. Sections of chapter 1 appeared in Helios 17 (1990) and Diacritics 22, no. 2 (Summer 1992). A shorter version of chapter 2 appeared in South Central Review 13, no. 2 (1989) and in Richard J. Golsan, ed., Fascism, Aesthetics, and Culture: Commitments and Controversies (Hanover: University of New England Press, 1992). A section of chapter 3 appeared under the title "Drole d'histoire, drole de recit: lire V Arret de mort" in Seminari Pasquali di analisi tes tuale, no. "HArrtt de mort" (Pisa: ETS Editrice, 1991). Chapters 5 and 6 contain passages from articles published in Studies in Twentieth-Century Lit erature 10, no. 1 (Fall 1985) and MLN 102 (1987). A section of chapter 7 is taken from "Gray Zones: Vichy, Maurice Blanchot, and the Problem of Aftereffect," in Nancy Harrowitz, ed., Tainted Greatness: Anti-Semitism, Preju dice, and Cultural Heroes (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1994). I thank the editors of these journals and presses for permission to reprint. The introduction, most of chapters 1,3,5, and 7 and all of chapter 4 appear here in print for the first time.

Introduction

Out of the Past

Every presentation of history must begin with awakening; in fact, it should deal with nothing else.

Walter Benjamin, Konvolut N

This book explores a convergence over the past twenty years of shared concerns among literary scholars and historians studying France since 1930. It is organized around a series of questions about the recent past and the assumptions on which inquiry into it is grounded. In what wayshow, when, and wheredoes historical understanding evolve when the memory of a specific period is contested among those who lived it and those whose access to it depends on the accounts of others? How, in particular, has it come to pass that received accounts of interwar and wartime France have been increasingly open to question? Does this belated questioning always pertain? Or is it peculiar to the period under study and, by extension, to a genealogy of contemporary historical experience? These questions do not amount to an argument, nor do they set forth on their own anything like a working hypothesis. In listing them, I mean to identify a range of issues and problems related to the study of France since 1930 as debated by a growing minority of critics, theorists, and interdisciplinary types from the declasse historian to the historically minded litterateur.1

This convergence is discernible first in a change of object that has cast the 1930s as a Janus-like decade, both conclusion of the Third Republic and prologue to the 1940-4 Etat Francais at Vichy. This model of concurrent decline and renewal remains contested. Some have trivialized it as contingent and relative, a result of passing time rather than anything more marked and meaningful. Others have seen instead the consequence of a turn (return?) to history associated with "new historicisms" and poststructuralist theorizings of culture. Yet others have linked it to counterhistories that revise received accounts with a polemical intent.2 My sense when I began this project about ten years ago was that the convergence of literary and historical concerns I had identified was more than a surface effect, that it was directed less toward the data on which historical understanding was produced than toward assumptions of method, object, and ambition on which this production was grounded. To state this somewhat differently, the change in question was less a matter of adjusting or correcting details than something more emphatic on the order of what historians of science have referred to as epistemological breaks (Gaston Bachelard) and paradigm shifts (Thomas S. Kuhn).

Scandal and Aftereffect grew from my overlapping interests in literary theory, France between 1930 and 1945, and the writing of history. The project took a decidedly critical turn once I realized the extent to which issues of writing historyinvariably also issues of writing in historyentered fully into the encounter between post-Enlightenment reason and the emergent technologies of communication analyzed by Jean-Francois Lyotard in conjunction with a postmodern condition of knowledge.3 Yet postmodernity should not be equated with a specific moment, doctrine, or set of practices. Following Lyotard, I take it less as a finite duration than as a conditiona precondition, reallyimposed by a shift from understanding measured as a concern for achieving adequate representation toward a looser appreciation of how signs circulate as images and simulacra. What, then, are the implications of this shift for inquiry into the recent past that it supplements? If modernity is inevitably no longer what it was twenty, thirty, or fifty years ago, what might it mean to think (rethink?) a determinate duration within it at a moment when the concerns of literary critics and theorists of culture converge increasingly with those of historians? What, finally, might this rethinking mean if and when it undermined received understanding by disclosing modernity as something other than what it had been taken to be?

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Scandal and Aftereffect: Blanchot and France Since 1930»

Look at similar books to Scandal and Aftereffect: Blanchot and France Since 1930. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Scandal and Aftereffect: Blanchot and France Since 1930 and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.