This edition published by Verso 2015

First published by the Institute of Phenomenological Studies 1968

The contributions Contributors 1968, 1969, 2015

The collection Verso 2015

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

www.versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78168-891-5 (PB)

eISBN-13: 978-1-78168-893-9 (US)

eISBN-13: 978-1-78168-892-2 (UK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

v3.1

Contents

Introduction

The Congress on the Dialectics of Liberation was held in London at the Roundhouse in Chalk Farm from 15 July to 30 July 1967. The present volume is a compilation of some of the principal addresses delivered on this occasion. I would like to outline in this brief introduction how the Congress came about and in particular why we, the organizers, arranged this meeting between these particular people, why we generated this curious pastiche of eminent scholars and political activists.

The organizing group consisted of four psychiatrists who were very much concerned with radical innovation in their own field to the extent of their counter-labelling their discipline as anti-psychiatry. The four were Dr R. D. Laing and myself, also Dr Joseph Berke and Dr Leon Redler. Our experience originated in studies into that predominant form of socially stigmatized madness that is called schizophrenia. Most people who are called mad and who are socially victimized by virtue of that attribution (by being put away, being subjected to electric shocks, tranquillizing drugs, and brain-slicing operations, and so on) come from family situations in which there is a desperate need to find some scapegoat, someone who will consent at a certain point of intensity in the whole transaction of the family group to take on the disturbance of each of the others and, in some sense, suffer for them. In this way the scapegoated person would become a diseased object in the family system and the family system would involve medical accomplices in its machinations. The doctors would be used to attach the label schizophrenia to the diseased object and then systematically set about the destruction of that object by the physical and social processes that are termed psychiatric treatment.

All this seemed to us to relate to certain political facts in the world around us. One of the principal facts of this sort was the war of the United States against the Vietnamese people. In this latter situation there seemed to us to be a violent transformation of the idea of the enemy. Firstly, the enemy became transformed into the inhuman: that is to say, men who embodied all the most detested and therefore externalized attributes of the men qualities such as underhandedness, cunning, meanness (the conservation of their supplies and supply-lines), violence (the wish to shit on us), and rape (the tearing apart of the Western-imposed family pattern with its neat analogue, the oriental brothel).

I recently met in Cuba a Vietnamese guerilla commandant who talked about how, while he was conducting an operation against the invading U.S. and mercenary forces, he knew that his wife and three children were being slaughtered in the next village. He knew that and yet he dispassionately and successfully carried out his military or counter-military work. This man acted by choice in a way that conscripted U.S. soldiers never can do they simply lose and are lost to their families and can never give anything up. One human fact that generates most terror in the first world, the Imperialist World, is the fact of choice, the beginning of freedom, of spontaneous self-assertion of persons or a whole people. For this reason, among others, the free opponent must be categorized as inhuman.

After the conversion, on these lines, of man into the inhuman, there is a further subtle metamorphosis. The inhuman become non-human. At this point they become the ultimate projected versions of ourselves, those bits of ourselves that we wish most finally to destroy in order to become Pure Being. If we cannot destroy these bits in ourselves, we have to destroy them in this outside version. The sub-human or non-human are totally destructible (witness a similar process with Abo-hunting, continued well into this century in Australia), and there can be no possibility of guilt. They have to be wiped out almost before they exist as the non-human in our metaphysical imaginations. They are of course wiped out by their being what they are which, of course, is what they are not. They just need some sort of coup de grce wrapped up in napalm. Then, we believe, we shall know where we are. Or we shall know where they are in our graves!

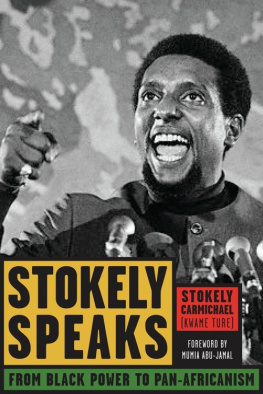

At the Congress, to bridge the gap between theory and practice, we invited people such as Gregory Bateson, Herbert Marcuse and Lucien Goldmann to represent the theoretical pole (in the best Greek sense of this term where theory is theoria or contemplation), and Stokely Carmichael, who is an activist in the most real sense of that term.

This book is centrally concerned with the analysis destruction destruction in two senses: firstly, the self-destruction of the human species by racism (Carmichael), by greed (Gerassi on Imperialism), by the erosion of our ecological context (Bateson, Goodman), by blind, frightened repression of natural instinctuality (Marcuse), by illusion and mystification (Laing and myself); secondly, closely interwoven with the first sense, these essays study the human conditions under which men destroy each other (Jules Henrys essay on Psychological Preparation for War in particular explored this subject). So it is a book about mass suicide and mass murder and we have to achieve at least a minimal clarity about the mechanisms by which these processes operate before we begin to talk about liberation. However, in each of the essays I have included there are at least strong hints as to how this liberation might be achieved.

It seems to me that a cardinal failure of all past revolutions has been the dissociation of liberation on the mass social level, i.e. liberation of whole classes in economic and political terms, and liberation on the level of the individual and the concrete groups in which he is directly engaged. If we are to talk of revolution today our talk will be meaningless unless we effect some union between the macro-social and micro-social, and between inner reality and outer reality. We have only to think back about the personal factor in Lenin that made it possible for him to ignore so much of the manoeuvrings of the super-bureaucrat Stalin until it was too late. We have only to consider the limited personal liberation achieved in the Second World (The Soviet Union and Eastern Europe). Then we get the point that a radical debourgeoisification of society has to be achieved in the very style of revolutionary work and is not automatically entailed by the seizure of power by an exploited class. We must never forget that conditions of scarcity inhibit though not necessarily prohibit personal liberation in this sense. But in the First World we have conditions of potential affluence which must be grasped and realized.