Ryan Swansons carefully researched and wonderfully nuanced study of baseballs declining race relations during Reconstruction sheds considerable light on this oft-neglected topic. A must-read.

Peter Morris, author of A Game of Inches and Level Playing Fields

Deeply researched and well written, Ryan A. Swansons When Baseball Went White carefully examines the mechanics of segregation that racially cleansed organized baseball during Reconstruction and in the process helped the game become our national pastime, at the expense of civil rights and racial justice. Swanson reveals, in fine detail, how a sport that would become a truly meaningful cultural practice and institution nevertheless became something less than it might have been.

Daniel A. Nathan, president of the North American Society for Sport History and author of Saying Its So: A Cultural History of the Black Sox Scandal

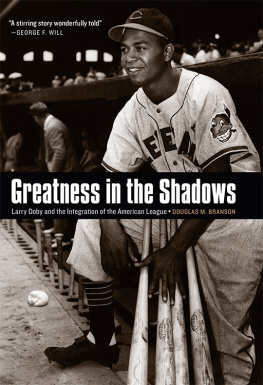

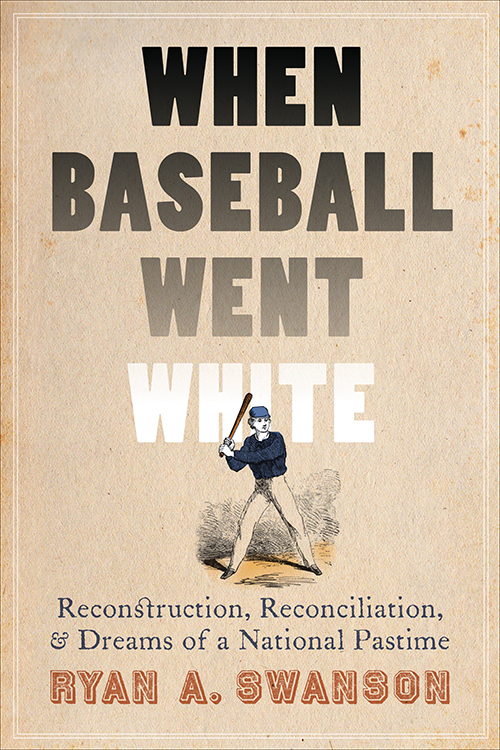

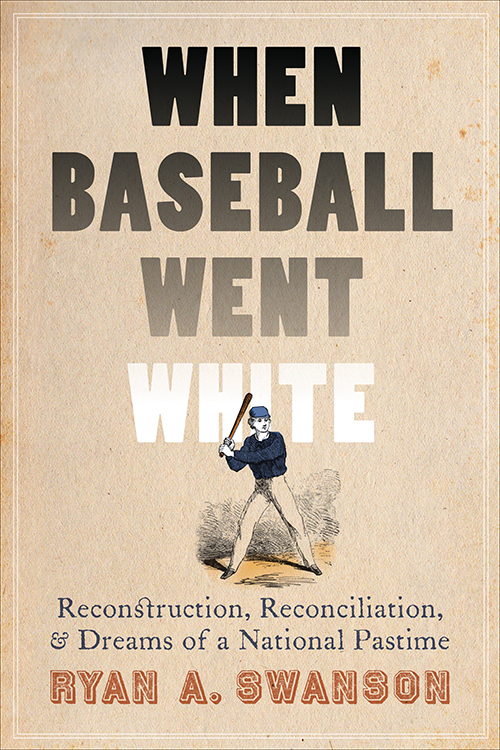

When Baseball Went White

When Baseball Went White

Reconstruction, Reconciliation, and Dreams of a National Pastime

Ryan A. Swanson

University of Nebraska Press | Lincoln and London

2014 by the Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska.

Cover image iStockphoto.com/nicoolay

All rights reserved.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Swanson, Ryan A.

When baseball went white: reconstruction, reconciliation, and dreams of a national pastime / Ryan A. Swanson.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8032-3521-2 (hardback: alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-8032-5518-0 (epub)

ISBN 978-0-8032-5519-7 (mobi)

ISBN 978-0-8032-5517-3 (pdf)

1. BaseballUnited StatesHistory19th century. 2. Racism in sportsUnited States. 3. Discrimination in sportsUnited States. 4. African American baseball playersUnited StatesSocial conditions. 5. United StatesRace relations. I. Title.

G 863. A 1 S 955 2014

796.35709034dc23

2013046027

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Contents

Illustrations

Introduction

To say, as many historians have, that baseballs racial segregation resulted from a gentlemens agreement is roughly the equivalent of asserting that the Civil War stemmed from a difference of opinion. Black and white men flocked to urban ball fields. But even as Reconstruction legislators debated how to guide four million former slaves along the path to citizenship, segregation emerged quickly in baseball. White baseball leaders barred black baseball players from joining white leagues and clubs and from owning baseball property. Due to this discrimination, black men created separate baseball communities of their own. By the time the National League ( NL ) organized in 1876 (as Reconstruction ended), baseball had become an overwhelmingly segregated sport.

How did this happen? Neither historians nor the legion of journalists and baseball writers who have penned, quite literally, hundreds of thousands of pages about the game have fully addressed this question. Instead, the issue of baseballs segregation has been mostly passed over. Nothing is ever said or written about drawing the color line in the [National] League, Sporting Life unapologetically observed in 1895. It appears to be generally understood that none but whites shall make up the League teams, and so it goes. This study focuses on the mechanics of baseballs segregation. The cities of Philadelphia, Richmond, and Washington DC anchor the analysis, allowing for the investigation of the North and South, both state and federal concerns, and black and white constituencies.

The fanatical desire by white baseball leaders to foster a national game was the preeminent force behind baseballs segregation. Northern baseball leaders worked tirelessly to spread baseballs popularity south of the Mason-Dixon line. White newspapermen and baseball writers spoke passionately about how baseball could heal and empower all Americans. White baseball players pursued civil rightsdamning reconciliation almost immediately after the Civil War.

Henry Chadwick, the self-proclaimed father of baseball, spoke repeatedly in reconciliationist terms, such as when he stated in 1866, Our national game is intended to be national in every sense of the word. Thus, ironically, in the name of creating a national pastime, baseball excluded black ballplayers.

In addition to sectional reconciliation, the removal of political radicals from positions of leadership within the white baseball community, violence against black players, and the unequal partitioning of baseball land made baseball an increasingly white game. So too did the trend of linking baseball with Confederate-memorializing causes. Similarly, the emergence of the open professionalization in the 1870s solidified many segregationist trends. Equally as important, the success of black ball clubs, even amid hostile circumstances (MemphisPublic Ledger: The colored base ball brigade is one of the greatest nuisances about the suburbs of the city. Enough lazy, thieving niggers swing a base-ball bat to raise a thousand bales of cotton, if they would), also influenced emerging baseball norms.

Baseball historians have mostly passed over Reconstruction-era baseballists. And those studies that have looked at Reconstruction baseball have focused primarily on the action on the field, rather than the broader context of baseball.

Baseball clubs carved out space to play the game in the midst of office buildings and factories. Some teams played in beautiful public parks; others made do with rough, trash-hewn vacant lots. The field standards were not high. Still, the bestthat is, flattest, driest, and most centrally locatedparcels of space often teemed with baseball activity. Baseballs most supportive newspaper, the New York Clipper, rejoiced in the chaotic activity at baseball hot spots: The way the balls fly in every direction is enough to remind a veteran of the army of the time when he found himself like the six hundred in the Crimea, who had balls to the right of them, balls to the left of them.

Competition for baseball grounds intensified when it became clear that there was money to be made charging admission to games. A baseball enclosure movement resulted. The battle for baseball space in Washington DC took place literally on the presidents doorstep. The White Lot, located between the Washington Canal (which today is Constitution Avenue) and the White House, played host to the Districts biggest games of the 1860s and 70s. Presidents occasionally The description of the fence, and then everything else, accurately depicted the focus on controlling baseball space.

Both black and white ballplayers played roles in shaping how baseballs segregated environment emerged and functioned. Many white clubs did what they could to keep black clubs from using the best fields and joining leagues. Black players, however, were hardly waiting idly for invitations to join white teams. In fact, very little evidence exists to suggest that black ballplayers during the Reconstruction period yearned for positions on white clubs, and certainly not at the expense of their black-led and black-populated clubs. Equality rather than social proximity was the goal. Charles Douglass, the son of Frederick Douglass, for one, knew what it was to work with white men (in the Freedmens Bureau and the Treasury Department), but he invested in playing baseball among black menfirst with the Washington Mutual Base Ball Club ( BBC ) and then the Alert.

White baseball players had professional opportunities that their black counterparts did not. It is estimated that professional ball tossers get paid larger salaries than three-fourths of the ministers of the Gospel of the United States, the

Next page