Brecht in Practice

Methuen Drama Engage offers original reflections about key practitioners, movements and genres in the fields of modern theatre and performance. Each volume in the series seeks to challenge mainstream critical thought through original and interdisciplinary perspectives on the body of work under examination. By questioning existing critical paradigms, it is hoped that each volume will open up fresh approaches and suggest avenues for further exploration.

Series Editors

Mark Taylor-Batty

Senior Lecturer in Theatre Studies, Workshop Theatre, University of Leeds, UK

Enoch Brater

Kenneth T. Rowe Collegiate Professor of Dramatic Literature &

Professor of English and Theater University of Michigan, USA

In the same series

Postdramatic Theatre and the Political: International Perspectives

on Contemporary Performance

edited by Jerome Carroll, Karen Juers-Munby and Steve Giles

ISBN 978 1 408 18486 8

Theatre in the Expanded Field: Seven Approaches to Performance

Alan Read

ISBN 978 1 408 18495 0

Howard Barkers Theatre: Wrestling with Catastrophe

edited by James Reynolds and Andrew Smith

ISBN 978 1 408 18439 4

Ibsen in Practice: Relational Readings of Performance, Cultural Encounters and Power

Frode Helland

ISBN 978 1 472 51369 4

Rethinking the Theatre of the Absurd: Ecology, the Environment

and the Greening of the Modern Stage

edited by Carl Lavery and Clare Finburgh

ISBN 978 1 472 59571 3

Related titles

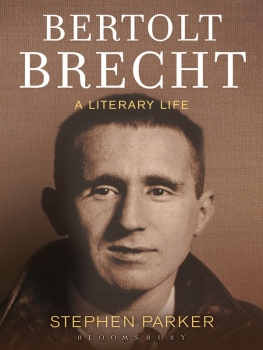

Bertolt Brecht: A Literary Life

Stephen Parker

ISBN 978 1 408 15562 2

Brecht on Art and Politics

edited by Tom Kuhn and Steve Giles

ISBN 978 0 413 77353 1

Brecht on Film and Radio

edited by Marc Silberman

ISBN 978 0 413 72760 2

Brecht on Performance: Messingkauf and Modelbooks

edited by Tom Kuhn, Steve Giles and Marc Silberman

ISBN 978 1 408 1545 5

Brecht on Theatre

edited by Marc Silberman, Steve Giles and Tom Kuhn

ISBN 978 1 408 14545 6

Brecht in Practice:

Theatre, Theory and

Performance

David Barnett

Series Editors

Enoch Brater and Mark Taylor-Batty

Contents

The majority of the research carried out for this book was undertaken while I was in Berlin, supported by a British Academy Research Development Award, and I am most grateful to the British Academy for its generous funding. I also thank Dr Geoff Westgate for his immeasurable time and patience in reading all the chapters, often several times. His observations and suggestions have made a real difference. Thanks also to Tom Kuhn and Steve Giles for providing me with pre-publication manuscripts of the new edition of Brecht on Theatre and of Brecht on Performance: the new translations now feature in this study. Mark Taylor-Batty has proved a trusty editor, and I have enjoyed working with Mark Dudgeon and Emily Hockley at Bloomsbury.

Bertolt Brecht (18981956) is something of a rarity in the field of theatre studies: not only did he gain an international reputation as a playwright, he also developed new ways of understanding theatre and new ways of making theatre as a director. This book focuses on his work as a theorist and practitioner of theatre and aims to introduce students, practitioners and those interested in theatre in general to the principles and nuances of Brechts thought and its implications for the practice of making theatre.

For all Brechts familiarity, he still remains remarkably misunderstood. The adjective taken from his name, Brechtian, often appears in books and newspaper reviews, but tends to be used to pick out features of a play or production that are more generic than specific. In the following quotations, Brechtian merely means revealing that spectators are made conscious of the fact that they are in a theatre:

Ramin Grays Brechtian flourishes getting members of the choir to read lines from a script down a microphone might be an alienation too far.

In a Brechtian coup de thtre, the director Richard Jones and designer Miriam Buether turn the lights on the audience, casting us as the towns burghers at a rancorous public meeting.

While such features are certainly found in Brechts theoretical and practical work, theatre history itself is littered with direct address to the audience and acknowledgement of the reality of the theatre, from the Greeks, via the medieval, renaissance and restoration stages, to the anti-illusionist experiments of the last century. Instead of pioneering such effects, it is perhaps more sensible to locate Brecht in this tradition. However, what is worth noting is that his purposes for exposing the reality of the theatre go unspoken in such references.

Michael Patterson observes a more commercial use of Brechtian and asks, can one claim that Brechts legacy is anything more than a matter of employing a more or less fashionable label to enhance theatre work ranging from performance art to agitprop?

Yet while Brecht may be misunderstood on paper, it is in the theatre itself where the most significant problems lie. In her study of Brecht in Britain, Margaret Eddershaw observes that by the 1970s Brecht has been appropriated. But the problem with appropriation [... ] is that its very purpose is to pull sharp teeth and nullify political bite. That is, theatres can use techniques they understand to be Brechtian without necessarily understanding where they come from or why they are being used.

This brief survey reveals that the term Brechtian, more often than not, can provide a misleading shorthand for ideas that are both specific and, as will be shown, complex. More importantly, in the examples given above, there is no mention of politics, despite the fact that will make clear, Brecht was not trying to teach lessons as such, but rather a new way of viewing the world and its workings. By pointing to instability and impermanence, Brecht wanted to show that the world could be changed. As such, Brechts is a fundamentally political theatre because it asks audiences not to accept the status quo, but to appreciate that oppressive structures can be changed if the will for that exists.

It is worth examining the possible reasons why politics is so frequently lacking from references to the Brechtian:

- Brecht was a Marxist, and Marxism, in the wake of the collapse of communism in Eastern Europe in the early 1990s, has in turn been disparaged and dismissed as an unworkable and unrealizably utopian set of ideas. If Brechtian has become a synonym for Marxist, then such an association may anchor Brecht in a discredited politics that many believe to have become superfluous or redundant. (Conversely, a successful Brechtian production may well help to redeem Marxisms tenets, for some in the auditorium at least.) In addition, theatre promoters and producers may feel or fear that a connection with Marxism will actually put audiences off a production.

- The political is often understood as concerning political parties, views and policies. It can harangue an audience and be presented in a ham-fisted way, that is, it can be partisan or propagandist. Brechts understanding of politics in the theatre is, as will be shown in , quite different from and far more subtle than this.

- It is possible to argue that there has not been a proper reception of Brechts ideas and practices in the UK (and, by extension, the USA), one that connects his method of dramatic analysis with the stagecraft he developed. While his plays have certainly been performed extensively, directors have rarely engaged with his approach to theatre-making. Brecht liked to work with an ensemble to develop the actors sensitivities to his method over time. It is more difficult to work through Brechts processes in theatre systems in which there are few ensembles and short rehearsal periods. Thus, the political aspects of Brechts theories and stagecraft have rarely been palpable in the English-speaking theatre.

Next page