Also by Stephan Thernstrom

Poverty and Progress: Social Mobility in a Nineteenth Century City

The Other Bostonians:

Poverty and Progress in the American Metropolis 18801970

Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups (ed.)

A History of the American People, Vols. 1&2

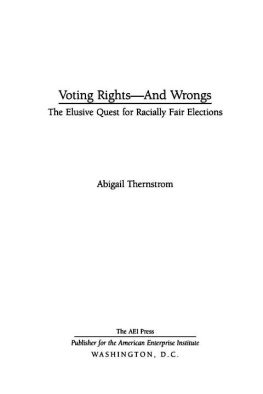

Also by Abigail Thernstrom

Whose Votes Count?: Affirmative Action and Minority Voting Rights

A Democracy Reader: Classic and Modern Speeches, Essays, Poems, Declarations and Documents on Freedom and Human Rights Worldwide (with Diane Ravitch)

T O M ELANIE AND S AM

Rockefeller Center

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

Copyright 1997 by Stephan Thernstrom and Abigail Thernstrom

All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form.

T OUCHSTONE and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster Inc.

Maps by Jeffrey L. Ward

The Library of Congress has cataloged the Simon & Schuster edition as follows:

Thernstrom, Stephan.

America in black and white: one nation, indivisible /

Stephan Thernstrom and Abigail Thernstrom.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

1. Afro-AmericansCivil rightsHistory20th century. 2. Afro

AmericansSocial conditions. 3. United StatesRace relations.

4. RacismUnited StatesHistory20th century.

I. Thernstrom, Abigail M., date. II. Title.

E185.61.T45 1997 9714078 CIP

305.896073dc21

ISBN-13: 978-1-4391-2909-8

ISBN-10: 1-4391-2909-6

Visit us on the Web:

http://www.SimonandSchuster.com

Acknowledgments

A BIGAIL T HERNSTROM is a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute, and for the extraordinary freedom to write full-time, she could not be more grateful. For their unwavering commitment to this seemingly endless project, particular thanks is owed to two remarkable men: Lawrence Mone, the Institutes president, and Roger Hertog, chairman of the board of trustees. They have provided a warm and nurturing home for an academic who chose to leave the academy.

The John M. Olin Foundation, the Lynde and Harry Bradley Foundation, the Smith Richardson Foundation, the Earhart Foundation, and the Carthage Foundation have also generously funded our research. Harvard University gave Stephan Thernstrom sabbatical leave in the academic year 19921993, and in the spring of 1993 Abigail Thernstrom was a visiting scholar at the Woodrow Wilson Center in Washington, D.C., a wonderful academic retreat that owes much to its director, Charles Blitzer.

Many friends and colleagues read the manuscript in whole or part. Douglas Besharov, Martha Derthick, Howard Husock, Morton Keller, Randall Kennedy, Andrew Kull, Stephen J. Markman, Walter Olson, Diane Ravitch, Charles Shanor, Ricky Silberman, Alex Von Hoffman, and James Q. Wilson all offered critical advice about specific chapters. Mary Ash, Henry Fetter, William Guenther, Edward Lev, and Stephen Teles stared at every page and provided highly detailed, invaluable feedback. We learned much from their painstaking reviews. Thanks to Roger Clegg of the Center for Equal Opportunity for catching numerous small errors in the hardcover edition. Finally, perhaps our greatest debt is to our son, Samuel Thernstrom, whose editorial skills are daunting and whose wise counsel on many matters of substance made us think and think again.

We were blessed with wonderful research assistants: Michael Burgmaier, Andrew Hazlett, Kevin Marshall, Todd Molz, Joel Pulliam, and Romney Resney. As a Harvard undergraduate, Joel worked for us part-time throughout his college career; for more than a year Andrew devoted his life to our project. Gina Hewes tabulated unpublished survey data that were important to our analysis. We owe a special thanks to them. Our warmest thanks as well to our literary agents, Glen Hartley and Lynn Chu, who have guided the book in countless small ways, and to our superb editor at Simon & Schuster, Robert Bender, who handled both book and authors with a firm and deft touch.

Inevitably, readers will wonder who wrote which chapters. This was truly a collaborative project; every chapter was a joint effort. The order of our names on the jacket has no significance; it resulted from the toss of a coin.

A.T.

S.T.

Lexington, Massachusetts

Contents

PART ONE

History

PART TWO

Out of the Sixties: Recent Social, Economic, and Political Trends

PART THREE

Equality and Preferences: The Changing Racial Climate

Preface to the Paperback Edition

M UCH HAS HAPPENED since this book went to press in early 1997. Perhaps most important, President Clinton launched an initiative designed to promote a national dialogue on controversial issues surrounding race, appointing the distinguished historian John Hope Franklin as head of an advisory board.

The appointment of Dr. Franklin put the issue of racial changethe central question in our booksquarely on the table. Every time people take a breath, Franklin has said, its in terms of color. As he described it, the brutal murder of a black man in Jasper, Texas, in June 1998 was not all that much of an aberration. We have at least several incidents like that every year.

This is a view very different from our own. From the response of citizens in Jasper and across the country, it was clear that this sort of incident now evokes horror among blacks and whites alike.

Implicitly or explicitly the question of change runs through every debate on race. John Hope Franklin is not alone, of course, in his pessimism. In July 1998, Bill Cosby s wife, Camille, writing on the murder of their son, described racism as omnipresent and eternalized in Americas institutions, media and myriad entities. Its certainly easy to get discouraged, and Camille Cosby had special reason for bitterness. But such misguided despair, we believe, threatens further progress. If racism is truly ubiquitous and permanent, then racial equality is a hopeless projectan unattainable ideal. Gloom becomes a dangerous, self-fulfilling prophecy.

In fact, both deep pessimism and complacent optimism seem to us unwarranted. America in Black and White has generated considerable controversy. Unfortunately much of that controversy results from a misrepresentation of

That is not what we believe, nor is it what we said. America remains a very color-conscious society, and true racial equality is a dream. There has been much progress, and there is still much to do. For instance, in 1964 only one in five white Americans had any black neighbors; today the figure is three out of five, a national average that includes whites living in states like Utah and Vermont where black residents are rare. And yet of course one needs only to walk the streets of, say, southeast Washington, D.C., to know that racial isolation is not a thing of the past.

In part, despair is the product of misguided expectations. We are passionate advocates of integration, and yet its unrealistic to expect that African Americans will one day be uniformly distributed across the residential landscape, such that they are 12 percent of every census tract. No other strongly defined group is so scattered. In the Boston area, Jews are concentrated in Brookline, Armenians in Watertown, Portuguese in Fall River, Cambodians in Lowell, Hispanics in Lawrence, and so forth. Again, this is not to say racial hostility plays an insignificant part in where blacks live; but one needs always to ask where weve been, how far weve come, and where were likely headed.

James Q. Wilson has described America in Black and White as a work that supports, with facts, what most people really believenamely, there is both good news and bad.