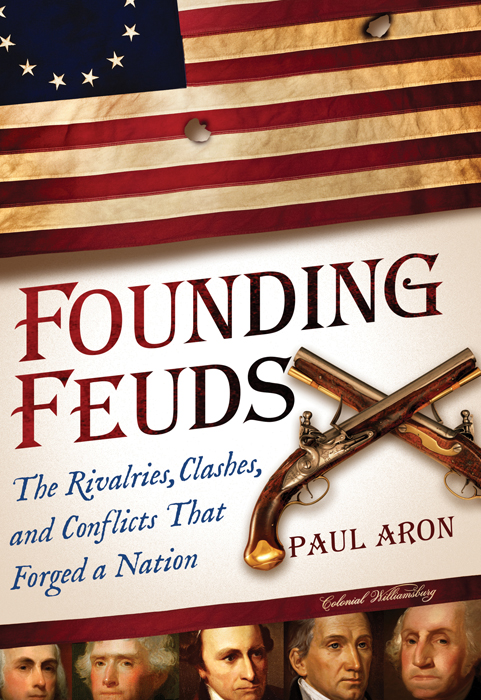

Copyright 2016 by the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

Cover and internal design 2016 by Sourcebooks, Inc.

Cover design by the Book Designers

Cover images used courtesy of the Colonial Williams Foundation. Full citations listed on .

Sourcebooks and the colophon are registered trademarks of Sourcebooks, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systemsexcept in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviewswithout permission in writing from its publisher, Sourcebooks, Inc.

This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold with the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering legal, accounting, or other professional service. If legal advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional person should be sought. From a Declaration of Principles Jointly Adopted by a Committee of the American Bar Association and a Committee of Publishers and Associations

Published by Sourcebooks, Inc.

P.O. Box 4410, Naperville, Illinois 60567-4410

(630) 961-3900

Fax: (630) 961-2168

www.sourcebooks.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Aron, Paul, author.

Title: Founding feuds : the rivalries, clashes, and conflicts that forged a nation / Paul Aron.

Description: Naperville, Illinois : Sourcebooks, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015050177 (pbk. : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: United States--Politics and government--1783-1809. | United States--Politics and government--1775-1783. | National characteristics, American--History. | Founding Fathers of the United States.

Classification: LCC E310 .A76 2016 | DDC 973.3092/2--dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015050177

CONTENTS

Desperate for French arms, Congress sent Deane and Lee to Paris. The two seemed as eager to undercut each other as to cut a deal with the French.

Enslaved Harry Washington took care of George Washingtons horses until Harry escaped from Mount Vernon. Harrys quest for freedom both paralleled and challenged Georges.

Just three years after the Revolutionary War ended, two patriot veterans again led forces into battle, this time against each other.

The Revolutions greatest orator took on the father of the Constitution, with the fate of that document hanging in the balance.

So far apart were their views of what America ought to be that they were, as Jefferson put it, daily pitted in the cabinet like two cocks.

The great allies of 1776 were bitter enemies when they faced each other in the election of 1800.

The two Federalist leaders so detested each other that in 1800, Hamilton preferred Jefferson over Adams, his own partys candidate.

Washington generally stood above the fray of feuding founders. So it was surely startling when Painewhose pen many equated to Washingtons swordexplained that the president stood alone because he so easily betrayed his friends, including Paine.

After Lyon, a Republican from Vermont, spit at Griswold, a Federalist from Connecticut, their fellow Congressmen witnessed a full-fledged brawl.

Some of the nastiest feuds played out in newspapers and pamphlets. Cobbett often wrote under the byline of Porcupine; Paine referred to him as Skunk.

The founders insulted each other so much that its surprising there werent more duels. But when the vice president faced off against the former treasury secretary, the result was deadly.

The president insisted that his former vice president be tried for treason.

Jefferson and Marshall were cousins, and their feud was deeply personal. It was also a test of the balance of power between the branches of government the two represented.

Once a key ally of Jefferson in Congress, Randolph broke with Jefferson to lead a group of Republicans appalled by Jeffersons embrace of federal power.

Wheatleys poems impressed, among others, Washington and John Hancock. Not Jefferson, who could not conceive of an African American, let alone a former slave, writing poetry.

Adams did not like the way he was portrayed in Warrens history of the Revolution. His enraged letters to Warren and her indignant replies, while not as lengthy as her history, fill hundreds of pages.

PREFACE

Thirteen clocks were made to strike together, John Adams wrote in 1818, recalling how the thirteen colonies united to seize their independence.

Adams knew this had been a tentative and tenuous unity. On July 1, the day before the colonists would vote for independence, John Dickinson of Pennsylvania had argued for delay, mustering the same arguments moderates had been making in the Continental Congress for months: that it might still be possible to reconcile with England, that Americans were not yet united behind independence, that America needed allies and troops before it could take on the worlds most powerful empire. To take on England prematurely, Dickinson said, would be to brave the storm in a skiff made of paper.

The day of the vote, Delaware supported independence only because of the last-minute arrival of Caesar Rodney, who had ridden through the night to break a tie among that colonys delegates. Pennsylvania supported independence only because Dickinson and fellow moderate James Wilson chose not to participate. And New York abstained, meaning one of Adamss thirteen clocks struck not at all.

Still, Adams was right to recall that, in July 1776, a great many Americans rallied round the cause. Dickinson, despite refusing to sign the Declaration of Independence, served as commander of a Philadelphia battalion and chaired the citys committee responsible for raising troops and building fortifications. That even twelve clocks struck together was, as Adams wrote, a perfection of mechanism, which no artist had ever before effected.

Or, perhaps, ever again effectedfor the unity did not last and has only rarely returned. The progress of evolution from President Washington to President Grant, wrote Henry Adams, famed historian and Johns great-grandson, was alone evidence enough to upset Darwin.

Most Americans would agree that the history of the nations leadership has hardly been an example of evolutionary progress. Mired in gridlock and repulsed by partisan bickering, we long for an era when our politicians were statesmen and philosophers.

These longings can blind us to the reality that our founders were as apt to disagree with each other as any twenty-first-century Democrats and Republicans, and their disagreements were at least as heated. Their feuds were driven by ideological differences, to be sure, but also by personal ambitions. And they were by no means above attacking their opponents, spreading stories of scandals both true and untrue, playing on voters emotions, and manipulating the electoral system. At stake, they believed, was the natureindeed the survivalof the American republic.

Take, for example, Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson. Hamilton thought Jefferson would import the terror of the French Revolution to America. Jefferson thought Hamilton would turn America into a monarchy. When Hamilton was secretary of the treasury and Jefferson secretary of state, George Washington attempted to mediate, with little success.

During the Revolution, Hamilton had served in the Continental Army. Jefferson spent much of the war at home. When British forces approached Monticello, Jefferson galloped away. Or, as Hamilton put it, The governor of the ancient dominion dwindled into the poor, timid philosopher, and instead of rallying his brave countrymen, he fled for safety from a few light horsemen.