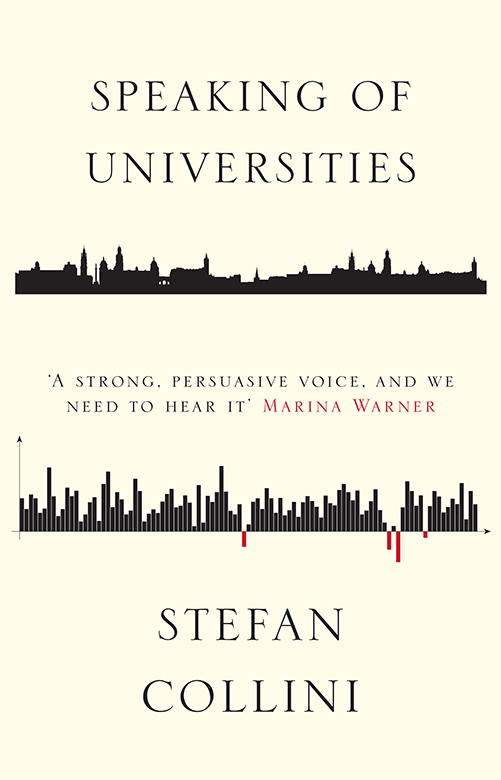

Speaking of Universities

STEFAN COLLINI

First published by Verso 2017

Stefan Collini 2017

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78663-139-8

ISBN-13: 978-1-78663-140-4 (US EBK)

ISBN-13: 978-1-78663-141-1 (UK EBK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

Typeset in Sabon by MJ&N Gavan, Truro, Cornwall

Printed in the US by Maple Press

The invasion of ones mind by ready-made phrases can only be prevented if one is constantly on guard against them, and every such phrase anaesthetizes a portion of ones brain.

George Orwell, Politics and the English Language (1946)

If we take the widest and wisest view of a Cause, there is no such thing as a Lost Cause because there is no such thing as a Gained Cause. We fight for lost causes because we know that our defeat and dismay may be the preface to our successors victory, though that victory itself will be temporary; we fight rather to keep something alive than in the expectation that anything will triumph.

T. S. Eliot, Francis Herbert Bradley (1927)

Contents

There is a lot of talk about universities these days, not least because there are now a lot of universities to talk about. In recent decades there has been an immense global surge in the numbers both of universities and of students, an expansion that, in purely numerical terms, quite dwarfs anything that has happened in the previous eight centuries or so during which versions of this curious institution have existed. Although this growth has taken place across developed and developing countries alike, the numbers are, as ever, most stunning in China, where it is claimed that over 1,200 universities and colleges have been established in the last twenty years alone. In Britain, the growth of higher education has not quite been on such a dramatic scale, but even so the speed of the changes here should not be underestimated. In 1990 there were forty-six universities in the UK educating approximately 350,000 students. Twenty-six years later, following the upgrading of the former polytechnics and the founding of a whole raft of new universities, often based on an earlier college of higher education, there are now more than 140 universities (or university-level institutions) with over two million students.

However, the changes have not been merely quantitative: the whole ecology of higher education in Britain has been transformed within the past generation. Most of the procedures governing funding, assessment, quality control, impact and so on that now occupy the greater part of the working time of academics were unknown before the mid-1980s. Forms of governance have changed no less significantly, even if these changes have been much less noticed: vestiges of academic self-government have largely been removed and replaced by the top-down control of a senior management team implementing the latest government directives. The range of subjects that can now be studied for a degree has hugely increased. New technologies promise to alter the most basic mechanics of the teaching process. Overseas students constitute an ever-higher proportion of the student body (over a third in some institutions). Globalization has been understood to require the setting up of campuses of British universities in other countries or the founding of partnerships with overseas institutions. And all of this is quite apart from the radical reshaping since 2012 of the funding system in England and Wales, though not Scotland, whereby direct public support of teaching in higher education has been replaced by a system of high fees supported by income-contingent loans, along with other market-oriented changes such as the encouragement of private providers, including both for-profit and not-for-profit institutions.

But although all of these changes mean that there is lots to talk about, there is widespread uncertainty about the premises and terms of discussion. The pace and scale of change have produced a sense of disorientation, an uneasy feeling that, as a society, we may be losing our once-familiar understanding of the nature and role of universities yet we have not so far replaced it with anything better. The language and categories used in politics and the media when discussing higher education only exacerbate the problem: although such categories may well be appropriate to talking about, say, the economics of an animal-feed processing plant, it is hard to rid ourselves of the suspicion that they may not provide an altogether adequate model for talking about universities. Of course, there are those who will say that it doesnt really matter how we talk about universities, since its all just talk. Such people can always produce from their pockets a massive solid lump of stuff called reality, and they will proudly demonstrate how talk simply bounces off it like raindrops off a bomb-shelter. What matters, they announce with their characteristic mixture of aggression and self-satisfaction, is whether the policies work. All this talk, especially the more high-toned versions of it, is simply waffle.

As false beliefs go, this takes some beating. It would not require any particularly fancy philosophical footwork to establish that our experience of the world is in part constituted by the categories we use. Words are not a kind of decorative wrapping paper in which meaning is delivered, with the implication that they could be stripped away, or others used in their stead, without making any difference to the real content. Concepts colonize our minds and we become used to thinking about ourselves and our world in their terms; our actions are only identifiable as this action rather than that action in terms of the language in which we describe them. In the swirling currents of assertion and assumption that make up our public discourse at any time, there are always a large number of vulgar errors passing themselves off as truisms, but the belief that words are just the decorative wrapping paper round experience is both one of the easiest to refute and one of the hardest to dislodge.

If you really believe that it doesnt matter in the least how we talk about universities, then you probably arent reading this book in the first place or, if you are, you will soon give up in irritation. But before you go, I would just like to ask you how you would decide any of the pressing policy questions about universities what you might call undeniable real world issues such as how to pay for them or how many people to admit to them or what to study in them and so on without using some description of what they are like and what they do and what they are for. And if you reply that the answers to those questions are obvious and anyway are practical matters, not requiring any fancy ideas or special vocabulary, then Id like to ask you where you think the terms in which you would frame your answers come from, because I could quickly show you that they were mostly not the descriptions used even a generation ago, let alone any further back in history. Our concepts and our language have their own histories, and the process by which one pattern of using them comes to be dominant at any given time is something that intellectual historians can chart with considerable precision. There is nothing natural or given about thinking of universities in terms of, say, social mobility or wealth-creation any more than there was about thinking of them in terms of character-formation or the propagation of Gods word.