LOCAL ELECTIONS AND THE POLITICS OF SMALL-SCALE DEMOCRACY

LOCAL ELECTIONS AND THE

POLITICS OF SMALL-SCALE

DEMOCRACY

J. Eric Oliver

with

Shang E. Ha and Zachary Callen

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 2012 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street,

Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street,

Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Oliver, J. Eric, 1966

Local elections and the politics of small-scale democracy / J. Eric Oliver with

Shang E. Ha and Zachary Callen.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-691-14355-2 (hardcover : alk. paper)ISBN 978-0-691-14356-9

(pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Local electionsUnited States. 2. DemocracyUnited States. I. Ha, Shang E.

II. Callen, Zachary. III. Title.

JS395.O55 2012

324.60973dc23 2011051379

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Sabon

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Raymond E. Wolfinger,

a great teacher, mentor, and friend

Contents

Acknowledgments

This book owes its existence largely to the support and encouragement of a number of individuals and institutions. We are greatly indebted to feedback from Sarah Anzia, Michael Bailey, Adam Berinsky, John Brehm, Jake Bowers, Andrea Campbell, Jamie Druckman, Brian Gaines, Daniel Hopkins, James Kuklinski, Paul Lewis, Paul Peterson, Robert Putnam, Tom Rudolph, Betsy Sinclair, and Cara Wong. Earlier versions of this work were presented at Harvard, Georgetown, and the University of Chicago, and we are grateful to these institutions for providing support of this work. We are especially grateful to Chris Berry, Elizabeth Gerber, William Howell, and Jessica Trounstine, who were incredibly generous in sharing data, time, and attention to this project. Matt Muttino and Ben Oren also provided outstanding research assistance. This research was financially supported by a Young Investigators CAREER grant from the National Science Foundation and by additional research support from the University of Chicago.

LOCAL ELECTIONS AND THE POLITICS OF SMALL-SCALE DEMOCRACY

INTRODUCTION

Who governs America?

Many people would say the United States is ruled by the presidentas the single office selected by all Americans and the head of the executive branch, the presidency commands more power than any other elected position in the land. Others might say that America is governed by Congresswith its ability to pass legislation, approve executive and judicial appointments, and exercise the power of the purse, Congress ultimately wields the upper hand in any political contest. Still others point to big corporations, unions, and other special-interest groups like the National Rifle Association (NRA) or the American Association of Retired Persons (AARP). These groups govern America not only through the direct lobbying of the various branches of government, but also in their ability to shape elections. Because candidates for congress and the presidency are so dependent on the efforts and campaign contributions of such interest groups, they repeatedly bow to their preferences.

This debate is probably familiar to most readers. It has animated American political discourse since the writing of the Federalist Papers. It speaks to fundamental concerns over the distribution of power and popular governance. It dominates the coverage of politics in the popular media. And its focus on national politics encapsulates the way most people conceptualize American governance. But this debate also suffers from a major problemit overlooks an enormous part of Americas governing structure.

Outside of Washington, there exists a largely unrecognized political entity that exerts an enormous influence on American society. It accounts for over $1.6 trillion in spending every year, roughly a quarter of the nations gross domestic product. It collects more

This political behemoth is local government and if we want to know who governs America, then we need to look beyond the forces that shape national politics and include the factors that influence local politics as well, particularly local elections. In doing this, however, we run into an immediate problem: we know comparatively little about local government and electoral politics in the United States. The overwhelming majority of people who make their living studying politics, such as political scientists, pollsters, pundits, and journalists, focus mostly on national elections. Rarely do they pay much attention to local contests. In fact, over the past fifty years, nearly all the published scientific research on American electoral behavior has focused on presidential or congressional races.

Although these experts have developed very good models of presidential and congressional elections, their explanations are actually ill suited for explaining local voting behavior. the criteria for judging incumbents performance are unclear; contentious issues are often hard to identify; and, unlike national contests, we dont have much of an understanding about what voters actually know about local candidates and issues. Most explanations of national voting not only are inappropriate for most local elections but also cannot account for why so many are uncontested, explain what drives evaluations of incumbents, or simply define the broader contours of local politics. While we may know a lot about how and why people vote for president, when it comes to explaining why Jane Smith beat Frank Jones for local supervisor, the best that most voting experts can offer is mere speculation.

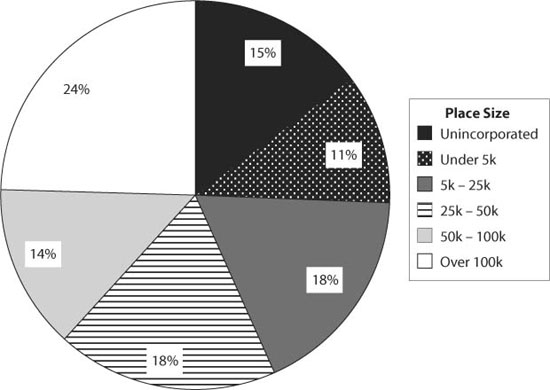

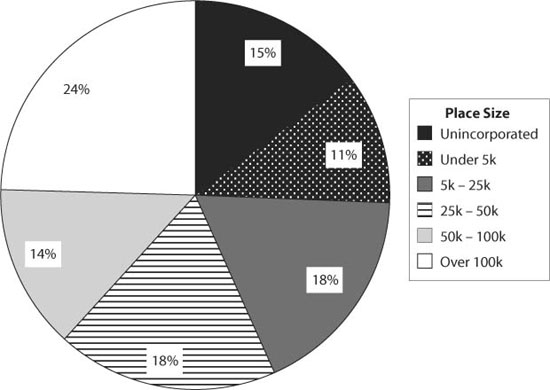

Unfortunately, the few existing studies of local elections are not very helpful either because they focus almost exclusively on voting in large cities. Indeed, most of what we know about local politics comes from the study of New York, New Haven, Atlanta, Chicago, Los Angeles, and a few other cities; meanwhile most Americans live in places that are much different from these big, urban centers. As illustrated in figure I.1, three in four Americans live in a community under 100,000 in size. Few of these places have the racial and economic diversity of a New York or Los Angeles. Few have their own airports, convention centers, public housing, newspapers, television stations, or hospitals. Nor do they typically have the corporate headquarters or large-scale business enterprises found in bigger cities. Given these differences, elections in Atlanta, Chicago, or Los Angeles will be more the exception than the typical case of local politics in America. In short, if we want to understand who governs America, we need to consider electoral politics in the smaller towns and cities where a majority of Americans actually reside.

Figure I.1. Distribution of the American population by place size. Source: 2000 U.S. Census, STF3C.

This, however, presents us with a very big challengehow do we compare the nearly 90,000 local governments that exist in the United States? America is not just differentiated by national and local governments or even by big cities and small towns, but by a plethora of smaller local municipalities, counties, school districts, and other special district governments. These smaller governments exhibit an incredible diversity in their size, economic and social composition, and civic and political institutions, a diversity that should also affect their local politics. One would expect that elections in affluent Malibu, California should be very different from gritty, industrial Riverdale, Illinois or bucolic Brenham, Texas. But how can we compare places that are so distinct without getting lost in each of their peculiarities? How can we identify who governs America when Americans live in so many types of places and under so many types of government? This book seeks to provide an answer.