F or the Leader of Her Majestys Opposition to miss the twice-weekly Prime Ministers Questions in the Commons is quite rare. It happens perhaps five or six times a year, usually when the opposition leader is away on a foreign visit. Normally his or her deputy will take over. In Neil Kinnocks case, of course, the stand-in is Roy Hattersley. But on Thursday 22 May 1986 not only did Neil Kinnock miss the twice-weekly confrontation with Mrs Thatcher, so too did Mr Hattersley. In an almost unprecedented move, it was a somewhat unprepared Denis Healey who had to face the Prime Minister across the dispatch boxes.

However, neither Neil Kinnock nor Roy Hattersley were on a foreign trip that day. Nor had illness or bad weather prevented them from making it to the Commons. Both men were well, and indeed working in central London, but felt they had more important business to see to. The National Executive Committee of the Labour Party was in the twenty-first hour of its hearings against certain members of the Liverpool Labour Party. Kinnock and Hattersley feared that if either of them left the meeting there might not be enough votes to secure a majority for expelling from party membership the chairman of Liverpool Councils Joint Shop Stewards Committee, Ian Lowes.

It was not that Lowes was particularly important, but that for Kinnock the whole issue of Militant was. The Labour leader wanted finally to deal with the Trotskyist group once and for all. It was more than a decade since Militants presence within the party had been brought to the attention of the party leadership. During that decade the party had first chosen not to take any action, and then failed to take effective action. Meanwhile Militant had grown from obscurity to national fame, from several hundred members to several thousand. All had been operating secretly within the structure of the Labour Party, and yet in reality operating as an independent revolutionary party. Indeed, with probably more influence and publicity than the Communist Party, and arguably more members, by 1986 Militant was effectively Britains fifth most important political party.

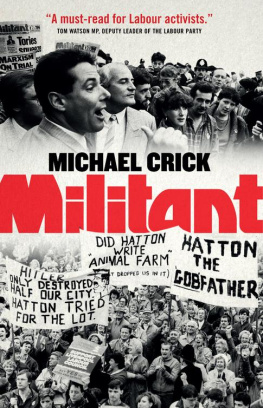

This book is the story of that party, probably Trotskys most successful group of followers in Britain, known internally as the Revolutionary Socialist League, publicly called the Militant tendency. far-left Labour Party pressure group: its programme, aims and policies are not just a more extreme version of the views of Tony Benn or Eric Heffer. Its philosophy descends directly from Marx, Engels, Lenin and Trotsky, and virtually nobody else. As a result the tendency believes in the kinds of methods, policies and goals that would be rejected totally by most ordinary Labour Party members. Because it is a revolutionary group, membership involves far more than just licking envelopes, arranging public meetings and sending out newsletters. To be a member of Militant is almost to adopt a new way of life, which consumes most of ones spare time, energy and cash. Many who eventually leave the tendency are burned out and never again become involved in politics. In some ways Militant has more in common with religion than with democratic politics.

The Labour Party battle over Militant has received a great deal of coverage in the press, on radio and on television, and media treatment has itself played an important part in the drama. But in spite of this extensive publicity few members of the public understand who or what the Militant tendency is. Militant with a capital M is often confused with militants with a small m. Some people may still think the term Militant tendency refers to the whole of the Labour far left and includes people such as Tony Benn. This false picture is often created, even encouraged, by certain parts of the press.

I first encountered Militant when I helped to set up a Labour Party Young Socialists branch in Stockport in 1974. It was only weeks before Militant took the branch over, and I watched with a mixture of annoyance and admiration as Militant carried out its operation. I realised then that Militant was more than just a newspaper, but I was not quite sure what. Frustrated by my work in the Young Socialists, I decided thereafter to concentrate on the Labour Party itself.

I did not really encounter Militant again until I became a journalist with ITN in January 1980, at a time when the Labour Party National Executive was being urged to take action against the tendency. It struck me then that Militant was a good story waiting to be told, and as the Militant saga continued over the next few years I became increasingly surprised that no journalist had ever made a serious attempt to tell it. Eventually I came to the conclusion that I would have to do the job myself.

So what is the Militant tendency? How exactly is Militant organised? Where does it get its funds? What precisely does it stand for? What is its ultimate goal? Why has it had so much success? To what extent has that success been exaggerated? How influential is the organisation? How will Militant do in the future? How effective has Neil Kinnock been in tackling the tendency? This book aims to deal with these questions, but it is also a book about the Labour Party itself, revealing much about how the party works at all levels and detailing the events that led to the leaderships eventual decision to take disciplinary action against Militant. The book is not meant to be a hatchet job on Militant. Certainly it contains things the tendency will not like to see in print, but Militants leaders will admit, I hope, if only to themselves, that it is a fair account.

The work is based partly on Militant, the tendencys newspaper, its other official publications and a large number of secret internal documents which have leaked out of the organisation. The most important source, however, has been a series of discussions and interviews with more than seventy people, nearly all of them Labour Party members. These have included Militant members, Labour Party officials, MPs, trade union officers and journalists. Particularly helpful have been more than twenty-five Militant defectors, former members of the tendency who have been prepared to talk about the organisation and their lives in it.

Militants leaders have given me only limited assistance. They did arrange interviews for me for the very I wrote, Militant Merseyside. Afterwards it was made clear that further help would depend on the Militant leaderships seeing that chapter. With some reluctance I showed it to them. Since then, they have always been too busy to meet me. However, perhaps I ought to thank Militant editor Peter Taaffe, if only for saving me considerable time and effort.

Many of the people I interviewed and who helped me wish to remain anonymous, for obvious reasons. I am grateful for the time they were able to spare me. Those whom I can thank publicly are, in alphabetical order: Graeme Atkinson, Mike Barnes, Robert Baxter, David Blunkett, Betty Boothroyd, Neil Brookes, Jeff Burns, Barrie Clarke, Tony Clarke, Ian Craig, Ken Cure, Sean Davey, Jimmy Deane, John Dennis, Kieran Devaney, Pete Duncan, Pat Edlin, Keith Ellis, Frank Field, Rob Gibson, Alistair Graham, Michael Gregory, Peter Hadden, John Hamilton, Terry Harrison, Richard Hart, Millie Haston, Jom Heeren, Ellis Hillman, James Hogan, Steve Howe, David Hughes, Mike Hughes, Sean Hughes, Charles James, Patrick Jenkin, Robert Jones, Gavin Kennedy, Jane Kennedy, Laura Kirton, Tony Lane, Peter Lennard, Martin Linton, Terry McDonald, Stewart Maclennan, Sinna Mani, John Mann, David Mason, Pat Montague, Sally Morgan, Jim Mortimer, Dean Nelson, Tony Page, Greg Pope, Allan Roberts, Eddie Roderick, Tom Sawyer, Adrian Schwarz, Eric Shaw, Ken Smith, Pat Stacey, Nigel Stanley, Alfred Stocks, Paul Thompson, Els Tieman, Jonathan Timbers, Russell Tuck, Charles Turnock, Reg Underhill, Mitchell Upfold, Neil Vann, Richard Venton, Mark Walker, Frank Ward, John Ware, Larry Whitty, Alan Williams, Willie Wilson, Alex Wood, Frances Wood and Margaret Young.