A few years ago, in Prague in Black and Gold , I wrote a history of my hometown from the sixth to the early twentieth century. I still remember how exhilarating it was to study the classic historians and what they said about kings, emperors, and the inevitable golem. It was harder to write the concluding pages about the funeral of T. G. Masaryk, first president of the Czechoslovak Republic, because on September 21, 1937, I had been there in the crowd, an eager boy of fifteen, sadly watching the flags, the casket on a gun carriage, and the soldiers marching by. Where was I to turn, writing about that event nearly sixty years later? There were reports in old newspaper files and the chronicles of professional historians, but overwhelmingly present was my own experience of that bleak morning, filtered through my eyes and ears, rising in my self.

These difficulties returned in full force when I decided to write about the years of the German occupation of Prague, 193945. Of course, I have relied on the narratives of historians and on newspaper reports, yet I was also constantly there, as I was not in the years of Charles IV or Rudolf II, in and of that world all these years, involved, walking, breathing, observing. Our grandfathers the existentialists are right: to be means to be such and such, to speak a particular language, to belong to a specific ethnicity, to profess a definite religion. But matters were rather more complicated in Prague during those years if you did not march in one of the neat ethnic battalions so dear to schoolbooks. Then, you had to be a Czech, a German, or a Jew, pure and simple, and unfortunately people did not know what to do with half Jews like me, straddling languages and ethnicities.

I should like to define what I am doing here as an almost impossible effort to present synchronically a public narrative of the various societies of Prague during the German occupation and my private story. When I write about politics and cultural life in the protectorate, I take my cue from what historians would do, and yet I have not excluded the story of myself, working whenever necessary with a change of perspective, however sudden and abrupt. I do not want to present any coercive interpretation of how warring societies and individuals relate to each other in bitter times, and I prefer rather to put the public narrative and the private story (if, after Paul Ricoeur, philosopher of memory and forgetting, such a distinction can be made at all) side by side, hoping that the reader will occasionally feel a shock of awareness, even a physiological one, when considering the circumstances, which often defied inherited vocabularies.

When I concerned myself with the past of my family in order to tell my own private story, I discovered to my great surprise that I came from immigrant stock on both sides; a hundred years later only one of my cousins and his small family continue to reside in that ancient city Prague, once peopled by multitudes of my uncles, aunts, their in-laws, children, and grandchildrena short and fragile encounter, considering the long span of Pragues history, yet brimming over with aspirations, individual fates, and tragedies. My South Tyrolean grandfather, who belonged to the minority of the Ladin peasants of the Gardena Valley, arrived in Prague on his trek to the north around 1885, and my Jewish grandfather, trying to escape the Czech anti-Semitism rampant in small Bohemian towns, came with his family as late as 1900, a remarkable coincidence of diverse origins, languages, and traditions found in the thicket of Pragues ancient urban community, continuously attracting people from all the many corners of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy.

I strongly believe that fin de sicle Prague had a touch of old New York about it, with so many different people all living under one civil law and, a little later, in Masaryks republic, under one constitution. The German occupation, driven by its own nationalism and triggering another one in response, for a while gravely undermined and almost destroyed the heritage of this multiethnic society, for centuries strongly alive and productive in Prague. And yet the city was indomitable, and the 3.5 million international tourists now visiting it each year hide rather than reveal that Prague with undiminished vitality and force again attracts new citizens, Russians, Poles, Ukrainians, a few Italians, Americans (nearly fourteen thousand in the 1990s but fewer now), and new Germans active in banking and business.

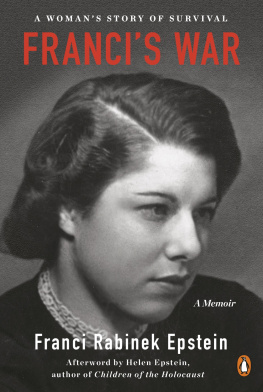

I dedicate this book, perhaps more personal than others I have written, to the memory of Hanna (1928-93). We fell in love shortly after the liberation of Prague in 1945, and we did not have to explain much to each other. Our Jewish mothers had died during the occupation, hers because the Jewish physician came too late, and mine in Terezn. And while many people returning to Prague from the concentration camps tried to emigrate immediately to America or Israel, we hoped that liberals of every shape would win in the elections of May 1946 and happily read newspaper articles by Ferdinand Peroutka, Pavel Tigrid, Helena Koeluhov, and Michal Mares, all united in opposition to the Stalinists, who were daily expanding their power in Czechoslovakia. After the Communist putsch of February 25, 1948, we had to go too, and while earlier we had playfully discussed what kind of car we would acquire in the grand West (Hanna wanted a red sports car, and I a dark green one), the question was now how to get out of the country without being caught and sentenced to seven years of hard labor.

Hanna, working as a secretary at the Czechoslovak-British Society, was under growing pressure from the secret police to deliver information about what went on in her office. I had my own worries, having participated in the march of two thousand students to Hrad

any Hillthe commanding site in Prague, where Hrad

any Castle had housed the rulers of Czechoslovakia for centuriesentreating the president, Edvard Bene, not to accept the imposition of a Stalinist government (he signed his capitulation while we were marching), and writing a dissertation on Franz Kafka and English literature. Hanna had to sell her mothers engagement ring so we could pay an aging Boy Scout late in 1949 to smuggle us through the woods and across the border to Bavaria, together with a few other students. And so it happened that we went through the refugee camps in West Germany, briefly worked for Radio Free Europe, and about two years later safely arrived at Idlewild Airport, New York, USA, with big rucksacks on our backs and a few pennies in our pockets. Prague, the ancient city, was of the past, but we did not cease to talk about its ambivalent charms, which were taking on, again, a golden hue.

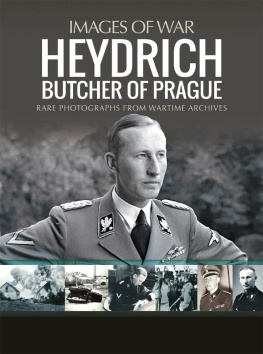

In official Prague, meanwhile, partisan proclamations dominated for a long time. Only in the late 1960s and early 1970s did Detlef Brandess magisterial work appear (in Germany), and Vojt

ch Mastns early study of the Czechs under Nazi rule (in the United States). Investigations of Jewish affairs ran into troubles of their own: the Communist regime, suspicious of Zionism, preferred anti-Fascism in general terms; thus Karel Lagus and Josef Polks book on Terezn was published by the League of Antifascist Fighters (1964), and Arnot Lustig, novelist and Auschwitz survivor, left for the United States (1969). Important studies of Jewish persecution during the protectoratei.e., H. G. Adlers There sienstadt and Livia Rothkirchens fundamental The Jews of Bohemia and Moravia: Facing the Holocaust (after she had sporadically published in Czech earlier)appeared abroad. Fortunately, by 1995, the Terezn Institute Initiative had published its first volume of international studies under the editorship of Miroslav Krn, and many sequels have followed since.

any Hillthe commanding site in Prague, where Hrad

any Hillthe commanding site in Prague, where Hrad  ch Mastns early study of the Czechs under Nazi rule (in the United States). Investigations of Jewish affairs ran into troubles of their own: the Communist regime, suspicious of Zionism, preferred anti-Fascism in general terms; thus Karel Lagus and Josef Polks book on Terezn was published by the League of Antifascist Fighters (1964), and Arnot Lustig, novelist and Auschwitz survivor, left for the United States (1969). Important studies of Jewish persecution during the protectoratei.e., H. G. Adlers There sienstadt and Livia Rothkirchens fundamental The Jews of Bohemia and Moravia: Facing the Holocaust (after she had sporadically published in Czech earlier)appeared abroad. Fortunately, by 1995, the Terezn Institute Initiative had published its first volume of international studies under the editorship of Miroslav Krn, and many sequels have followed since.

ch Mastns early study of the Czechs under Nazi rule (in the United States). Investigations of Jewish affairs ran into troubles of their own: the Communist regime, suspicious of Zionism, preferred anti-Fascism in general terms; thus Karel Lagus and Josef Polks book on Terezn was published by the League of Antifascist Fighters (1964), and Arnot Lustig, novelist and Auschwitz survivor, left for the United States (1969). Important studies of Jewish persecution during the protectoratei.e., H. G. Adlers There sienstadt and Livia Rothkirchens fundamental The Jews of Bohemia and Moravia: Facing the Holocaust (after she had sporadically published in Czech earlier)appeared abroad. Fortunately, by 1995, the Terezn Institute Initiative had published its first volume of international studies under the editorship of Miroslav Krn, and many sequels have followed since.