Born in 1929, Robert E. Denney served with the U.S. Marines in China and on Guam. In 1950, he entered the Army, serving in the Korean and Vietnam Wars. He was wounded in action in Korea and was awarded the Silver Star, Bronze Star with V device, and Purple Heart. Graduating from the Warrant Officers Flight Program in 1956 as a helicopter pilot, he went on to become an Assistant Project Officer for the testing of low-level navigation systems for helicopters. For his performance during these tests, he was awarded the Army Commendation Medal. For various actions in Vietnam, he was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross, Bronze Star (OLC), several Air Medals, and another Purple Heart. On retirement in 1967 as a major in the Signal Corps, Denney pursued his lifelong interest in the Civil War, an avocation he attributed to the influence of a high school history teacher who in the early 1940s, peppered his American History classes with tales he remembered [from his youth] as told by the veterans, and stories of rural Indiana in the late 1800s.

After his years in the military, Denney earned a Masters degree and became a computer systems consultant. Married with four children and three grandchildren, he passed away in 2002 and is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

This country will be drenched in blood. God only knows how it will end. Perhaps the liberties of the whole country, of every section and every man will be destroyed.

William T. Sherman, December 1860

This is no time for man to war against man. The forces of Heaven are loose and in all their fury, the wind howls, the sea rages, the eternal is here in all his majesty.

Private Day, off Cape Hatteras, N.C., January 1862

[B]ut just then a white flag was seen to flutter from the rebel works, which proclaimed that the finale had been reached. Then one long, joyous shout echoed and re-echoed along our lines. Its cadence rang long and deep over hill and valley until we caught the glad anthem and swelled the chorus with our voices in one glad shout of joy. It was a glorious opening for the Fourth of July.

Corporal Barber, at the surrender of Vicksburg, July 1863

the country mourned the loss of one of its more illustrious defenders, the brave and noble McPherson. When his death became known to the army that he commanded, many brave and war-worn heroes wept like children. It is said that Gen. Grant wept when he heard of his death.

Corporal Barber, outside Atlanta, July 1864

[I] regard it as my duty to shift from myself the responsibility of any further effusion of blood, by asking of you the surrender of that portion of the C. S. Army known as the Army of Northern Virginia.

Gen. U. S. Grant to Gen. Robert E. Lee, April 7, 1865

Sterling Signature

NEW YORK

An Imprint of Sterling Publishing

387 Park Avenue South

New York, NY 10016

STERLING SIGNATURE and the distinctive Sterling Signature logo are trademarks of Sterling Publishing Co., Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

2011 by Robert E. Denney

Distributed in Canada by Sterling Publishing

The text featured in this edition is abridged from The Civil War Years: A Day-by-Day of the Life of a Nation originally published by Sterling Publishing Co., Inc., in 1992.

Page ii: Union flag (top), Confederate flag (bottom)

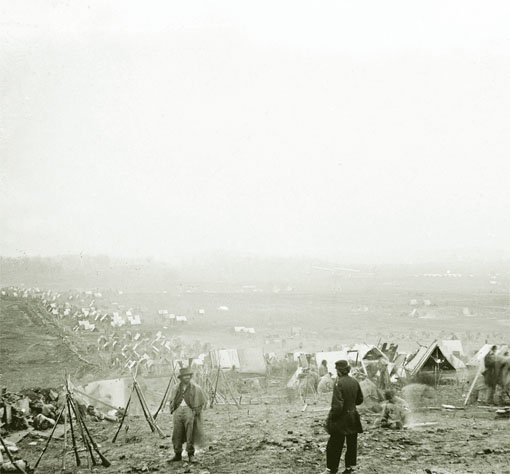

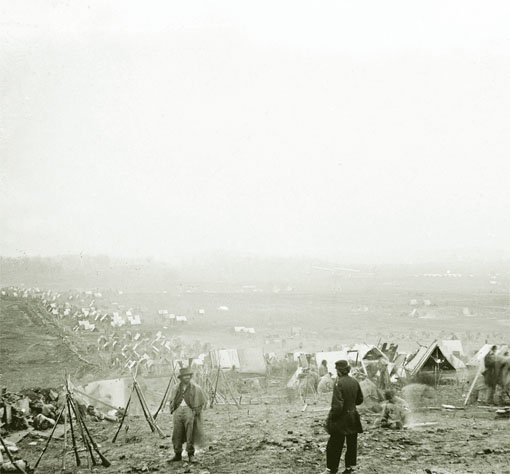

Facing page: The Battle of Nashville, December 16, 1864

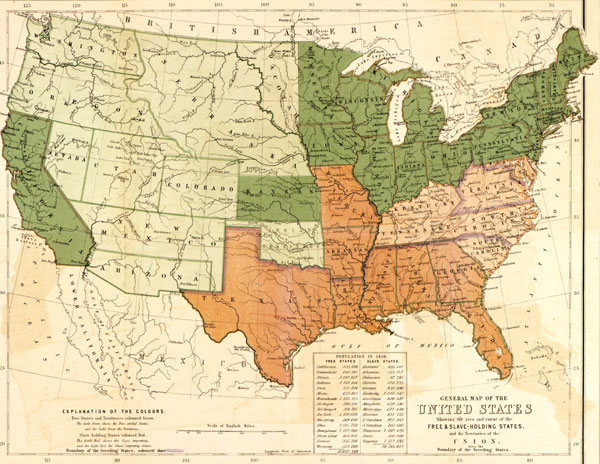

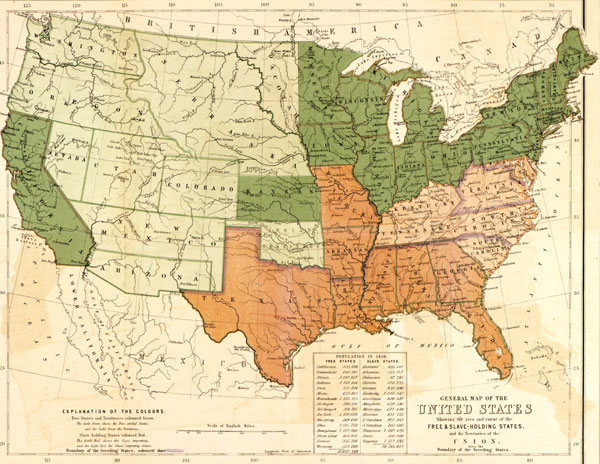

Page vi: United States map c. 1860s

Cover design: Kimberly Glyder

Interior design: Oxygen Design/Sherry Williams

All rights reserved

ISBN: 978-1-4027-7866-7

Sterling eBook ISBN: 978-1-4027-8926-7

For information about custom editions, special sales, premium

and corporate purchases, please contact Sterling Special Sales

Department at 800-805-5489 or specialsales@sterlingpublishing.com.

I T WAS DONE. The South had been defeated, the Union restored, and it was time to go home to other pursuits and to get on with life.

At the camps outside Washington, in neighboring Virginia and Maryland, the last muster rolls of the Union troops who had participated in the Grand Review were prepared by the company 1st Sergeants and attested to by the Commanding Officers. Discharge papers were prepared, accounts settled, and the soldiers began their journey home, for the first time in a long time unencumbered by muskets and cartridge boxes. A cadre remained to complete the housekeepingcompiling the records, preparing them for storage, etc., work that would go on for months.

But the war didnt just end with the Grand Review. Many armed troops were still in the field, and much was to be done to gather these men in and effect their surrender. This epilogue summarizes the final stages of the war.

JUNE 1865

The political prisoners held at various facilities around the country were released and sent home. Some had been incarcerated for up to two years.

The British government officially withdrew belligerency rights from the Confederate government.

In Galveston, Tex., Confederate Gen. E. Kirby Smith officially surrendered, accepting the terms outlined in New Orleans on May 26th. On June 3rd, the Southern naval forces on the Red River officially surrendered.

President Andrew Johnson appointed provisional governors to the various states of the late Confederacy.

On the last day of June, the Lincoln conspirators were found guilty by the military court.

Sgt. Lucius Barber, Co. D, 15th Illinois Volunteer Infantry, had reenlisted for a period of three years on his last reenlistment, believing that he would be discharged at the end of the war.

Barber, since the Grand Review, had been sightseeing in Washington and resting up after his long march from South Carolina. On June 8th, Barber left Washington for Illinois, passing through Harpers Ferry on the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad to Parkersburg, W.Va., where he boarded the steamer G.R. Gilman on the 10th. With many stops along the way, he passed Cincinnati on the 12th, and arrived in Louisville with his unit on the 15th. On the 20th he was paid up to date, receiving $369.00.

On the 21st, Barbers unit was on the march again, this time for St. Louis. The reaction to this unexpected event was rather angry:

Marched at 5 AM. Took the transport Camilla for St. Louis. Are just shoving off from shore and slowly dropping down stream. This sudden move still remains a mystery to us. Somethink we are going to be mustered out. Somethink that we are going to some distant post to do garrison duty. We veterans cannot believe that the government will be guilty of so great an injustice as still keeping us in the service after we have so faithfully performed our part of the contract.

The government, considering that they had at least another year to go on their enlistments, was going to put them to work on the frontier. This was finally disclosed to the troops on June 25th, at which time the reaction became even angrier:

At St. Louis. Our astonishment and anger knew no bounds when we found out that we were to be sent to the frontier to fight Indians. Our brigade commander, General Stolbrand, was the author of this outrage. The recruits had no reason to complain as they were bound to service one year if their services were required, but we had fulfilled our part with the government to the very letter. Symptoms of mutiny began to manifest itself. A large number of the veterans took French leave, determined not to go. To quiet the tumult, orders were issued to grant furloughstwenty percent of all enlisted men, but about ninety percent were given to the veterans. I obtained a furlough without the asking.

Next page