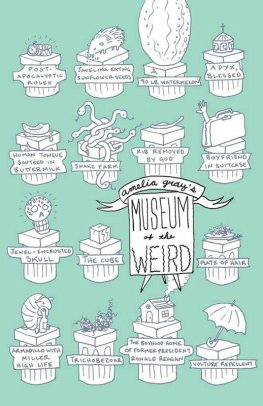

Amelia Gray

Museum of the Weird

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following publications in which these stories first appeared: Babies in Guernica and The Austin Anthology: Emerging Writers of Central Texas; Trip Advisory: The Boyhood Home of Former President Ronald Reagan in McSweeneys Internet Tendency; This Quiet Complex in Monkeybicycle; The Cottage Cheese Diet and There Will Be Sense in DIAGRAM; Code of Operation: Snake Farm and The Cube in Spork; A Javelina Story in Bust Down the Door and Eat All the Chickens; The Picture Window and Fish in Keyhole Magazine; The Darkness and The Tortoise and the Hare (as Beating the Odds) in Dispatch Litareview; Waste in Annalemma Magazine; Love, Mortar in Bound Off; Death of a Beast in Juked; Diary of the Blockage in Caketrain; Vultures in Swivel; The Movement in Storyglossia; Dinner in Shelf Life Magazine; The Vanished in Sleepingfish; The Suitcase in The Sonora Review;; and Thoughts While Strolling in Alice Blue Review.

Gratitude is owed to Featherproof Books, Justin Boyle, Carmen Edington, Jon Knutson, and the kids in the van.

One morning, I woke to discover I had given birth overnight. It was troubling to realize because I had felt no pain as I slept, did not remember the birth, and in fact had not even known I was pregnant. But there he was, a little baby boy, swaddled among cotton sheets, sticky with amniotic fluid and other various baby goops. The child had pulled himself up to my breast in the night and was at that moment having breakfast. He looked up and smiled when I reached for him.

Hello, I said.

I bundled my sheets and my mattress pad into a trash bag and set it by the door. I got into the shower with my new baby, because we were both covered in the material of his birth and were becoming cold. I soaped him up with my gentle face soap. He laughed and I laughed, because using face soap on an infant is funny. I toweled him off and wrapped him in a linen shirt.

On the walk to the store, I called my boyfriend, Chuck.

I had a baby overnight, I said.

Chuck coughed. I am not amenable to babies, he said.

I looked down at the baby. He was bundled up in the fine shirt and smiled as if he was aware of the quality of the shirt, and enjoyed it. I am in love with this baby, I said, and thats that.

At the grocery, I bought baby powder, diapers, two pacifiers, and a box of chocolate. I walked us home, fit a diaper on the baby, and ate a piece of chocolate. Chuck came over and said that perhaps he was amenable to babies after all, and we fell asleep together with the baby between us. The baby had not cried all day and neither had I.

The next morning, we woke to discover I had once again given birth, this time to a little girl. The babies were nestled together between us on the bed, and my spare sheets were ruined. I handed the babies off to Chuck and sent him to the shower. I bundled up the spare sheets and placed them by the other bag of sheets. Then, I got into the shower with Chuck. It was a nervous fit, with the two of us and the babies.

These babies are so quiet, said Chuck. I love them, too. But I hope you dont have another one overnight.

We all had a good laugh. The next morning, there was another baby. And another. And another. And another.

And that brings us to today.

Rogers assigned route had him picking up medical waste at most of the plastic surgery offices in town. He smelled it on his skin by the end of the day. The plastic surgery places were less of a hassle than the hospital and worlds away from the free clinic. After a day full of sharps and used lipo tubes and ruptured implants and the weight of discarded flesh, he tried not to think about the contents of the barrels. He sometimes wore his nose-plug at home.

The long shower he took after work helped a little, and it was good to finally smell the world around him as he dried himself off. From where he stood in his bedroom he could smell the dust in the carpet, the vinegar smell of his freshly washed windows, and the wooden bed frame. He detected the slightest hint of mold in the wall, which didnt surprise him, as the duplex was fifty years old at least and sagging. After a good rain, the mold smelled damp and sweet.

Roger enjoyed his evenings when Olive, his neighbor on the other side of the duplex, was cooking. Olive worked as a line cook at a vegetarian restaurant and spent her evenings frying meat. The smells slipped under the door connecting their apartments and seeped out of closed windows to surround the house. One night, Roger smelled something new and knocked on their connecting door.

Hello, nose, Olive said. Its chorizo. Behind her, a saut pan sizzled with orange meat.

My grandmother made that in the morning, Roger said. Olive leaned against the doorjamb. She was still wearing her hairnet from work. Probably with eggs, she said.

And cheese, and corn chips sometimes.

A fine breakfast. She gestured towards the pan with the spatula. Im making hamburgers. I mix it with ground chuck. I have enough for another one, if you want.

They sat on the floor to eat. The meat soaked orange fat into the bread. The two of them worked through a thick pile of napkins. Olives apron was a cornflower blue hospital gown that Roger had picked up for her months ago. Her skin looked pale next to it.

You have a lovely collarbone, Roger said.

She looked at him. Lymph nodes, she said. And salivary glands. She took a bite and chewed thoughtfully. They make chorizo with the lymph nodes and salivary glands of the pig. Cheeks, sometimes.

He swallowed. Cheeks.

Pig to pork, Olive said. When does the change happen? At death, its a dead pig. At the market, its a pork product. But when does the grand transformation take place? After the animals last breath? When its wrapped and packed?

It would be horrible to be wrapped and packed.

Olive shrugged. Some might think so. The pig might think so, if it wasnt well on its way to becoming pork. But its lucky, in a way. Not everything gets to transform. Her collarbone ducked in and out of the neck of her hospital gown as she talked.

Roger returned his sandwich to its plate. Im going to have the rest of this at work tomorrow, he said.

She unlocked her side of the connecting door for him. Think about it, she said. The pig gets to become pork. The rest of us simply go from live body to dead body.

* * *

At work, Roger loaded bags into heavy drums and wheeled the drums from the loading dock to his truck using a dolly and securing straps. He rolled the drums onto the trucks hydraulic lift, operated the lift, and drove to the next office and eventually to the incinerator. The metal drums warmed in the sun in the bed of the truck.

One of the big autoclaves was broken at the sterilization plant, and he got to take his time on his last pickups. He talked to the nurses and drove aimlessly around town. He sat at a covered picnic table five hundred feet from his truck and ate a late lunch. The chorizo had solidified in the fridge overnight, giving the burger neon orange spots. Roger removed the nose-plug and clipped the lanyard to the lapel of his jumpsuit.

When he was young, one of his teachers in grade school showed the class a video of a slaughterhouse. It began slowly, the picture grainy and unclear, the storyline featuring frowning men in white lab coats and packages of meat on a store shelf, but a brief segment at the middle of the video showed the actual process of the killing; the animals screaming and bleeding between metal railings, their heads swinging.