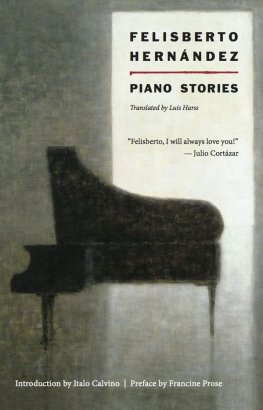

Felisberto Hernandez - Piano Stories

Here you can read online Felisberto Hernandez - Piano Stories full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2014, publisher: New Directions, genre: Prose. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Piano Stories

- Author:

- Publisher:New Directions

- Genre:

- Year:2014

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Piano Stories: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Piano Stories" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Piano Stories — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Piano Stories" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Felisberto Hernandez

Piano Stories

Lighting the Lamps: A Preface

In the library of a university at which I taught for one semester, there was a pleasant, brightly lit browsing lounge furnished with comfortable sofas and chairs. Lined up neatly on the shelves, the newest books with the shiniest covers winked enticingly at students and researchers rushing by on their way to the stacks and never managed to attract more than one casual lounger or browser.

I was that solitary browser. The New Books Lounge was where I hid out between classes, and where I first read an essay by Italo Calvino in which he praised the fiction of Bruno Schulz and that of the Uraguayan, Felisberto Hernndez, in whose stories, wrote Calvino, The narrator, who is usually a pianist, is invited to lonely country houses where wealthy maniacs set up complicated charades in which women and dolls change places. [Hernndez] has a few things in common with Hoffmann, but in fact he is like no one else.

I had named my first son Bruno, partly after Bruno Schulz, whose work, at the time I read the Calvino essay, still seemed like something of a secret: a secret which, happily, has come out in the years since then. And naturally, I was curious to read the work of a writer who Calvino considered so singular and put in such singular company.

Amazingly, the university library had the first volume of the Mexican edition of Felisberto Hernndezs stories: Nadie encenda las lmparas. No One Had Lit the Lamps.

Just translating the title exhausted the absolute limits of my Spanish. I borrowed the book from the library and eagerly took it home, as if Id forgotten that I couldnt read the language.

I kept the book the entire term (no one else requested it) and sometimes opened its pages and picked out recognizable words. I couldnt imagine what miracle I expected so that these isolated Spanish words pianos, hands, light, water, women, furniture, hair would organize themselves into stories and reveal their complex meanings.

The term ended. I returned the book needless to say, unread. Later, I often found myself in the library or bookstore, idly looking for Hernndezs work in English, excitedly but without the faintest hope, the way we may look up an old friends name in a local phone directory, though we know that it has been years since that friend left town, or died.

One decade after I pretended to read Felisberto Hernndez in a language I couldnt read, his book was published in English by Marsilio as Piano Stories, translated by Luis Harss, with an introduction by Italo Calvino, and now, two more decades later, this out-of-print edition is being republished by New Directions.

The story of Felisberto Hernndezs life sounds like a tale he might have written: fantastic, grotesque, and slyly funny. In a preface to his eloquent translation, Luis Harss recounts the unspectacular life of the man whom readers and critics often refer to as Felisberto, perhaps because the name is so exotically attractive, or perhaps because we feel an intimate kinship with this suffering brother-artist, with his inflated ego, his pitiful obscurity, his genius: the gifted tortured eccentric we still think of as The Artist, on the model of Kafka, Van Gogh, Joseph Cornell, and not Julian Schnabel.

Felisberto Hernndez was born in 1902, in Uruguay, where he died, sixty-two years later. He made his living as a pianist, accompanying silent films in cinemas and later playing small concert halls throughout Uruguay and Argentina. Once, he spent some shadowy months on a grant in France, writes Harss. He married four times; was a great eater and raconteur at literary soirees; had a passion for fat women; loved to improvise on the piano in the style of various classical composers; once toured Argentina with his own trio, other times with a flamboyant, bearded impresario called Venus Gonzlez. He preferred to write in shuttered rooms or basements; suffered a life-long emotional dependence on his mother; was haunted by morbid vanity and a sense of failure; became ill-humored and reactionary in middle age; and died of leukemia, his body so bloated that it had to be removed through the window of a funeral home in a box as large as a piano.

For much of his life, Felisberto kept a journal in a secret code resembling musical notation. Obsessed with the past and with memory, he was a fervid admirer of Proust. His literary fortunes could hardly have been more dismal or more like the musical careers of the hapless young men he sends, in his fiction, to entertain in the homes of maniacs; his wives were obliged to support him. He paid for the printing of his early books, which included decoded fragments from his journal. Three collections of stories were commercially published, though commercially is an overstatement. Luckily, he had champions and patrons at home and among the South American expatriate community in Paris. One supporter, the Uruguayan critic and philosopher Carlos Vaz Serrerra, wrote, There may be only ten persons in the world interested in these stories, but I am one of them.

Ten was evidently not enough. Felisberto died poor, his stories out of print. And he has only become more well known in Latin America since a three-volume edition of his writing appeared in Mexico in 1983. (The rights to his work are in a chaos, struggled over by interested parties, including his nieces.)

Perhaps Felisbertos singularity kept him from gaining wider acceptance. There is no school he belongs to, no category he fits. Calvino was right in claiming that Hernndez was unlike anyone else especially the artists with whom he has been grouped: he is neither a Surrealist, a naf, nor a Magical Realist.

The writer he most resembles is, as Calvino said, Bruno Schulz. Both men share a gift for smudging the crisp edge of the real, for making the non sequitur seem the logical next step, for restoring the world to that Edenic and sinister childhood state in which flowers, fruit, the weather, insects, all manner of inanimate objects lead dangerous, hidden, and polymorphously erotic lives of their own.

Certain writers invite us to peer into peoples windows, through the brilliant polished glass of Prince Andrs palace or the Duchesse de Guermantes salon, through the dusty screens of the farms that dot Alice Munros Ontario and the trailers in which Raymond Carvers characters stumble and lose their way. Such writers invite us to watch our neighbors at typical or extraordinary moments, men and women being their highly specific individual selves, and at the same time behaving so very much like we do, that we may feel we have looked through their windows and directly into their souls.

But there are other writers who make us feel that we have been invited through a door, a doorway barely cracked open, invited at great personal cost into the writers own house: into Gregor Samsas apartment, the bedroom of Molloys mother, or the seedy tropical hotels in which Jane Bowless serious ladies chatter desperately as they grapple with their private terrors.

Its darker in these houses than in the clear light of day; the floor plan seems highly eccentric. And yet we never doubt that the writer knows the way, as he or she leads us further and further into some cellar or crawl space, where we witness a vision of such startling beauty that it flares up like an old-fashioned phosphorus match and illuminates our whole lives.

Its almost as if we must read such fiction in a different state of consciousness, with our disbelief suspended more firmly than usual, with an acceptance of illogic that mimics the way we apprehend reality in our dreams. Its not at all like reading descriptions of dreams in fiction, which (with rare exceptions, such as Anna Kareninas dream) often ring false: apt, stagily convenient soundings of a characters unconscious. To read writers like Bruno Schulz and Felisberto Hernndez is less like hearing about a dream than like actually having one: familiar notions of causality no longer apply, and yet the sequence of events seems correct, as it does in dreams, even when people and objects behave in unlikely ways. In Hernndezs vividly animistic world, objects have desires, as we do, though mostly what they want is to change into other objects, into living creatures or body parts.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Piano Stories»

Look at similar books to Piano Stories. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Piano Stories and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.