Andrea Barrett

Voyage of the Narwhal

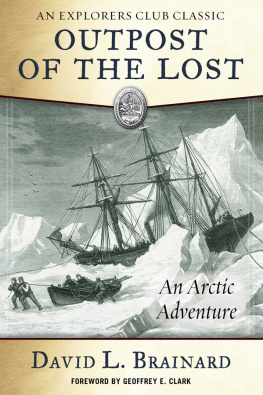

I hate travelling and explorers. Amazonia, Tibet and Africa fill the bookshops in the form of travelogues, accounts of expeditions and collections of photographs, in all of which the desire to impress is so dominant as to make it impossible for the reader to assess the value of the evidence put before him. Instead of having his critical faculties stimulated, he asks for more such pabulum and swallows prodigious quantities of it. Nowadays, being an explorer is a trade, which consists not, as one might think, in discovering hitherto unknown facts after years of study, but in covering a great many miles and assembling lantern-slides or motion pictures, preferably in color, so as to fill a hall with an audience for several days in succession. For this audience, platitudes and commonplaces seem to have been miraculously transmuted into revelations by the sole fact that their author, instead of doing his plagiarizing at home, has supposedly sanctified it by covering some twenty thousand miles. Journeys, those magic caskets full of dreamlike promises, will never again yield up their treasures untarnished. A proliferating and overexcited civilization has broken the silence of the seas once and for all. The perfumes of the tropics and the pristine freshness of human beings have been corrupted by a busyness with dubious implications, which mortifies our desires and dooms us to acquire only contaminated memories. So I can understand the mad passion for travel books and their deceptiveness. They create the illusion of something which no longer exists but still should exist, if we were to have any hope of avoiding the overwhelming conclusion that the history of the past twenty thousand years is irrevocable.

CLAUDE LEVI-STRAUSS, Tristes Tropiques (1955)

I try in vain to be persuaded that the pole is the seat of frost and desolation; it ever presents itself to my imagination as the region of beauty and delight. There the sun is for ever visible; its broad disk just skirting the horizon, and diffusing a perpetual splendor. There snow and frost are banished; and, sailing over a calm sea, we may be wafted to a land surpassing in wonders and in beauty every region hitherto discovered on the habitable globe What may not be expected in a country of eternal light?

MARY SHELLEY, Frankenstein (1818)

He was standing on the wharf, peering down at the Delaware River while the sun beat on his shoulders. A mild breeze, the smells of tar and copper. A few yards away the Narwhal loomed, but he was looking instead at the partial reflection trapped between hull and pilings. The way the planks wavered, the railing bent, the boom appeared then disappeared; the way the image filled the surface without concealing the complicated life below. He saw, beneath the transparent shadow, what his father had taught him to see: the schools of minnows, the eels and algae, the mussels burrowing into the silt; the diatoms and desmids and insect larvae sweeping past hydrazoans and infant snails. The oyster, his father once said, is impregnated by the dew; the pregnant shells give birth to pearls conceived from the sky. If the dew is pure, the pearls are brilliant; if cloudy, the pearls are dull. Far above him, but mirrored as well, long strands of cloud moved one way and gliding gulls another.

In the water the Narwhal sat solid and dark among the surrounding fleet. Everyone headed somewhere, Erasmus thought. England, Africa, California; stony islands alive with seals; the coast of Florida. Yet no one, among all those travelers, who might offer him advice. He turned back to his work. Where was this mound of supplies to go? An untidy package yielded, beneath its waterproof wrappings, a dozen plum puddings that brought him near to tears. Each time he arranged part of the hold more of these parcels appeared: a crate of damson plums in syrup from an old woman in Conshohocken whod read about their voyage in the newspaper and wanted to contribute her bit. A case of brandy from a Wilmington banker, volumes of Thackeray from a schoolmaster in Doylestown, heaps of hand-knitted socks. His hands bristled with lists, each only partly checked-off: never mind those puddings, he thought. Where were the last two hundred pounds of pemmican? How had half the meat biscuit been stowed with the candles and the lamp oil? And where were the last members of the crew? In his pocket he had another list, the final roster:

ZECHARIAH VOORHEES, Commander

AMOS TYLER, Sailing Master

COLIN TAGLIABEAU, First Officer

GEORGE FRANCIS, Second Officer

JAN BOERHAAVE, Surgeon

ERASMUS D. WELLS, Naturalist

FREDERICK SCHUESSELE, Cook

THOMAS FORBES, Carpenter

Seamen:

ISAAC BOND, NILS JENSEN, ROBERT CAREY,

BARTON DeSouza, IVAN HRUSKA,

FLETCHER LAMB, SEAN HAMILTON

Fifteen of them, all hands counted. Captain Tyler, Mr. Tagliabeau, and Mr. Francis, who together would have charge of the ships daily operations, were experienced whaling men. Dr. Boerhaave had a medical degree from Edinburgh; Schuessele had been cook for a New York packet line; Forbes was an Ohio farm boy whod never been to sea, but who could fashion anything from a few odd scraps of wood. Of the seven unevenly trained seamen, Bond had reported for duty drunk, and Hruska and Hamilton were still missing.

Their companions, invisible in the hold, waited for directions waited, Erasmus feared, for him to fail. He was forty years old and had a history of failure; hed sailed, when hardly more than a boy, on a voyage so thwarted it became a national joke. Since then his lifes work had come to almost nothing. No wife, no children, no truly close friends; a sister in a difficult situation. What he had now was this pile of goods, and a second chance.

Still pondering the puddings, he heard laughter and looked up to see Zeke hanging from the rigging like a flag. His long arms were stretched above a thatch of golden hair; as he laughed his teeth were gleaming in his mouth; he was twenty-six and made Erasmus feel like a fossil. Everything about this moment was tied to Zeke. The hermaphrodite brig about to become their home had once been part of Zekes familys packet line; with his fathers money, Zeke had ordered oak sheathing spiked to her sides as protection against the ice, iron plates wrapped around her bows, tarred felt layered between the double-planked decks. In charge of the expedition and hence, Erasmus reminded himself, of him Zeke had chosen Erasmus to gather the equipment and stores surrounding him now in such bewildering heaps.

Where was all this to go? Salt beef and pork and barrels of malt, knives and needles for barter with the Esquimaux, guns and ammunition, coal and wood, tents and cooking lamps and woolen clothing, buffalo skins, a library, enough wooden boards to house over the deck in an emergency. And what about the spirit thermometers, or the four chronometers, the microscope, and all the stores for his specimens: spirits of wine, loose gauze, prenumbered labels and glass jars, arsenical soap for preserving bird skins, camphor and pillboxes for preserving insects, dissecting scissors, watch glasses, pins, string, glass tubes and sealing wax, bungs and soaked bladders, brain hooks and blowpipes and egg drills, a sweeping net too many things.