Chris Bachelder

The Throwback Special

For Padgett Powell

and always for Jenn

What, then, is the attitude and mood

prevailing at holy festivals?

Johan Huizinga, Homo Ludens

Today in Sports History

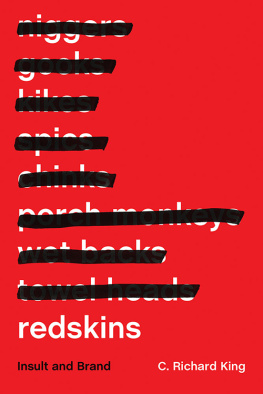

NOVEMBER 18, 1985 WASHINGTON REDSKINS quarterback Joe Theismann, 36, suffers a career-ending compound fracture of the right leg on a sack by New York Giants linebacker Lawrence Taylor during a telecast of ABCs Monday Night Football. On first-and-ten from their own 46-yard line, early in the second quarter with the score tied 77, the Redskins attempt a trick play called a flea flicker. Theismann hands the ball off to tailback John Riggins, who takes several steps forward and then pitches the ball back to Theismann. Theismann looks to throw a deep pass, but he immediately faces pressure from Giants linebacker Harry Carson. Theismanns in a lot of trouble, says play-by-play commentator Frank Gifford. He steps forward into the pocket to avoid Carson, but Taylor, rushing from Theismanns blind side, leaps onto his back. Theismann ducks, and as Taylor falls and spins, his thigh strikes Theismann in the calf with enough force to snap the bones of Theismanns leg. It sounded like two muzzled gunshots, Theismann says later. Taylor stands quickly, waving to the Redskins sideline for medical help. ABC decides to show the reverse angle replay twice. And I suggest, Gifford says before the replay, if your stomach is weak, you just dont watch. When you see a competitor like Joe Theismann injured, especially this severely, I dont think anyone feels good about it, commentator O. J. Simpson says. Theismann receives an ovation as he is carried from the field at RFK Stadium on a stretcher. I just hope its not his last play in football, says commentator Joe Namath. Jay Schroeder replaces Theismann at quarterback, and the Redskins defeat the Giants 2321. Theismann, a former league MVP who had played in 163 consecutive games, never plays again.

WOULD IT

The woman at the front desk was squinting disapprovingly at her monitor. She touched her temple with her fingertips, and blinked slowly, as if reluctant to resume eyesight. She did not look up.

Is there any way that. .

The woman twisted her thumb ring, grimaced at the data on the screen. She was not, she made clear, available for hospitality. The thumb ring, purchased from a street vendor, was vaguely Celtic in design.

Would it be possible, at all, to check in?

Roberts voice was too high. He often had to remind himself to deepen his voice, but invariably it would rise again to a pitch that assured his auditor that he was nonthreatening. It was an animal signal; he might as well have had a shaggy tail tucked against his inseam. I submit to you, the pitch of his voice said. I acquiesce to the large desk, that brass pineapple. I would like another mint, but I will not take one. That clock behind me is immense, and though it appears to be slow, I will live by its decree.

No, the woman at the front desk said, without looking up from her monitor. Im sorry, she added.

Robert nodded. Thank you, he said in a voice so deep that it hurt his larynx. The woman vacated her position, indicating that the interaction was complete. Robert watched her as she walked into a secret room behind the front desk. Though a visitor, he felt abandoned.

Robert had been, characteristically, the first of the men to arrive at the hotel, a two-and-a-half-star chain off Interstate 95 recognized in online reviews for its exceptional service, atrocious service, pretty fountain, and bedbugs. He felt now the familiar burden of concern. It seemed, this and every year, profoundly unlikely that each of the other twenty-one men would show up. Standing alone by the fountain, holding a duffel bag and a football helmet, Robert had the anxious sensation that the ritual, seemingly so entrenched, was in fact precarious. He was dimly aware that his habit of arriving prematurely had more to do with apprehension than eagerness. He felt a need to count himself present.

The celebrated fountain in the center of the lobby was dry and quiet, cordoned off by yellow tape. A placard that partially obscured a notice from the department of health implored visitors to pardon the commitment to excellence. Scattered in the fountains arid basin was a constellation of coins, whitish and crusted. Robert gripped the yellow tape, stared at the desiccated wishes. There was nothing, he considered, more dry than an inoperative fountain.

Robert exited the lobby beneath an arbor of plastic vines. At the end of the hallway, the heavy door to the conference room was locked, but Robert peered through its small window. The carpet, a honeycomb design, was new, he thought. On the floor, propped against the lectern, was a framed poster of an icy summit that Robert could not recall from previous years. He tried the door again, but it was still locked. As he backed away, he nearly knocked over a wooden easel, which displayed, on a piece of creased foam board, the weekend schedule. The conference room, according to the schedule, was booked solid for a corporate retreat by a group called Prestige Vista Solutions. Robert double-checked the dates: November 17 and 18. Could he be, he wondered, in the wrong hotel? But no. There was the fountain, the huge clock, the weird brass pineapple. The dusty, waxen leaves of the arbor. He turned the foam board over, placing the schedule facedown against the easel. The reverse side displayed a bar code sticker and an inexpert pencil sketch of a dolphin.

Back in the lobby, Robert chose a stuffed chair in the corner where he could see anyone who arrived or departed. The day outside was raw and gray, the low clouds bulging with cold rain. Robert unsnapped the chinstrap from the helmet, and from his duffel bag he removed a sewing kit a wicker box with a hinged lid that had originally belonged to his first wifes aunt. In the kit he found a faded and lumpy pincushion originally made to resemble either a tomato or an apple or a strawberry. Robert selected a needle from the pincushion, then a spool of white thread from the tidy spool boxes in the kit. He threaded the needle, realizing as he did so that he had become someone for whom threading a needle is difficult. Robert began to mend the chinstrap, which had split longitudinally when he snapped it on last year. The white of the thread matched closely, though not exactly, the white of the chinstrap.

WHEN CHARLES PASSED THROUGH the automatic doors into the hotel lobby, he saw Robert sleeping in a chair so large and soft that it appeared to be slowly ingesting the unconscious man. Robert clutched a chinstrap to his chest like a rag doll. A small wicker box with a hinged lid sat overturned by Roberts feet, and a half dozen spools of thread, having emerged from the box, seemed to be making their perilous journey to the sea. Charles sat down on the edge of a soft chair, and Robert awoke, feeling embarrassed to be seen sleeping, then irritated for being made to feel embarrassed.

Hello, Robert, Charles said.

I tried to check in, Robert said, wiping the edges of his mouth with the collar of his shirt. He struggled to get out of the chair, reminding himself of his father. He knelt on the floor to pick up the errant spools of thread. Charles assisted by retrieving two spools, annoying Robert.

Charles asked Robert how his year had been.

Not that great, Robert said. What time is it?

The wicker sewing kit reminded Charles of his grandparents cabin on Lake Michigan. There had been a box there though much larger, and not wicker full of games and toys. While the adults talked and drank, he would sit on the floor, playing Barrel of Monkeys or Lincoln Logs. There had been another toy, a sketch of a bald mans head encased in transparent plastic. With a magnetic stylus you dragged dirty iron filings to the mans head, giving him hair, a mustache, a beard. The filings clung to the stylus like filthy moss. The mans mood was entirely dependent, Charles had discovered, on the angle of the eyebrows.

![Chris Crawford [Chris Crawford] - Chris Crawford on Game Design](/uploads/posts/book/119438/thumbs/chris-crawford-chris-crawford-chris-crawford-on.jpg)