Augusto Monterroso - Complete Works and Other Stories

Here you can read online Augusto Monterroso - Complete Works and Other Stories full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2013, publisher: University of Texas Press, genre: Prose. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Complete Works and Other Stories

- Author:

- Publisher:University of Texas Press

- Genre:

- Year:2013

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Complete Works and Other Stories: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Complete Works and Other Stories" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Complete Works and Other Stories — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Complete Works and Other Stories" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Augusto Monterroso

Complete Works and Other Stories

~ ~ ~

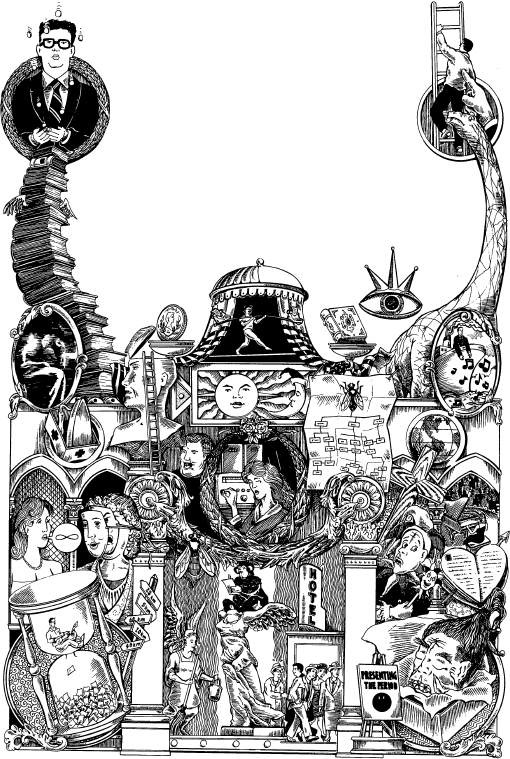

BEFORE AND AFTER AUGUSTO MONTERROSO

For Brbara Jacobs

Augusto Monterroso is one of the very few Latin American authors whose works are truly tailor-made for a comparative perspective on world literature. Rather than comparing Monterroso to other authors of the Western tradition, as seems to be the case for Latin American authors who are world renowned, one normally ends up perusing that tradition in terms of someone like Monterroso. Within the historical but not aesthetic relativity of such an assertion, the truth is that Monterroso is a precursor in many ways, serving as an enhancing presence for what is generally understood by Latin American literature. In the lecture series Six Memos for the Next Millennium (trans. Patrick Creagh, 1988), Italo Calvino discusses succinctly the universality and indispensability for literature of Lightness, Quickness, Exactitude, Visibility, and Multiplicity. Toward the end of the second lecture Calvino states:

Borges and Bioy Casares put together an anthology of short extraordinary tales (Cuentos breves y extraordinarios, 1955). I would like to edit a collection of tales consisting of one sentence only, or even a single line. But so far I havent found any to match the one by the Guatemalan writer Augusto Monterroso: Cuando despert, el dinosauro [sic] todava estaba all (When I woke up, the dinosaur was still there). (51)1

Among those uncontestable (because they are neither static nor purely Western) aesthetic values that Calvino does not discuss is the added element of greater ambiguity produced by Monterrosos original Spanish. By resorting to the perfectly grammatical deletion (surely on purpose) of the gendered Spanish pronoun he or she that could precede despert, Monterroso enriches his text twofold. In this regard most if not all of the criticism about Monterroso and his work finds connections with the elements Calvino considers essential for literature. The linkages with other world authors from this century and before who have espoused parallel distillations about what good literature is and has always been will also become evident when reading the stories collected here.

Perhaps of equal importance in Calvinos admiration for Monterroso is the mention of Borges and Bioy Casares, whose 1955 collection serves to mark a before and after. Much like his Argentine counterparts, Monterrosos notions of intertextuality, allusions, direct references, quotations, tributes, winks, and all the other anxieties of influence critics try to find in brilliant literature comprise an immediate and overwhelming legacy to Latin American literature. Yet his critics says Monterroso is a postmodern minimalist (along the lines of Heraclitus, Blake, Kierkegaard, Krauss, Cioran, or Canetti); Monterroso is a humorist (along the lines of Lem, Coover, D. Barthelme, or Groucho Marx); Monterroso is a philosopher (along the lines of Emerson, Nietzsche, or Wittgensteins zettel). Yet he denies having anything to do with those models. As of this writing, such has been his modus vivendi for fifty years, and there is every hope among his huge Latin American following that there will be another Golden anniversary. The fact, however, is that for many years Monterroso was a writers writer. Now, despite his innermost wishes, he finds himself more deservedly canonical than any of the recently translated authors from the region.

At this juncture a generation of Latin American and Spanish readers and writers has read Monterroso, and his writing will continue to create precursors, happy emulators, and epigones. The rediscovery, critical institutionalization, and even popularization of his work in languages such as English are due to very evident reasons. Like the permanent lesson that can be culled from Borges in Kafka and His Precursors, Monterroso allows his readers to say Hey, [fill in the author] writes just like Monterroso. That is to say, the singularity of his literature brings him to the forefront. Nevertheless, he has never really cared about the commercialism that can propel an author to fame, perhaps because recognition among select intellectual minorities seems to be enough for him. However, as any theorist would argue, texts take on a life of their own once their authors hand in their manuscripts. Let us see, then, how we arrived at the present translation of his first two books.

What is the before and after to all this? Who is Augusto Monterroso? He has never really needed an introduction in Latin America, at least since Jos Donoso wrote the original Spanish version of The Boom in Spanish American Literature: A Personal History (trans. Gregory Kolovakos, 1977) a quarter of a century ago. Interestingly enough, other than a passing reference in interviews, the only time Monterroso has spoken about his personal life is in English, in some comments included in Angel Floress Spanish American Authors: The Twentieth Century (1992). He states there that he comes from the Central American upper middle class, yet has had a life of economic hardship. Born in Honduras in 1921 to a Guatemalan father and Honduran mother, he is still a Guatemalan citizen. But what he seems to emphasize is the intellectual chronology of his learning:

My studies were interrupted at an early age by my rejection of school and by my parents continual travels between two different countries. Ever since I was a child, however, I have felt an inclination for the arts and especially for literature. I gave myself unknowingly to my love for them without thinking that one day I would be a writer. In other words, I am an autodidact; but I ought to add that what I learned in primary school and in a home full of literary and artistic currents had always pointed me in that direction (558).

He does add that while working at odd jobs and as an accounting assistant at a butcher shop he managed to study foreign languages (among his translations of books and essays are Swifts A Modest Proposal) and to attend night classes at the Guatemalan National Library, where he eagerly read the Spanish classics which are the foundation of my literary formation.

What Monterroso neglects to mention in typically modest fashion, although he refers to it in interviews, is his thorough knowledge, fondness for, and dialog with Greek and Roman classics (Catullus, Aesop, Juvenal, Vergil), Cervantes (for many years he taught a seminar on Don Quixote at the National University of Mexico), Gngora, Shakespeare, Johnson, Byron, Dante, Rilke, and, among his contemporaries, Borges. He is also quite reticent about his more contemporary influences, readings, and literary likes and dislikes. Monterroso is an outsider whose strength derives less from his experiments with those influences than from his vitality in producing from them an even more daring literary effect. But above all, his statement is not a euphemistic appraisal of his political commitment to progressive causes and the consequences he assumes as a result of his stance.2 Wisely, instead of contributing to biographical fallacies, Monterroso lets his literature speak for if not about him. Suffice it to say that at this point his work has been translated into all the major languages of the world, including recent translations of the short stories collected here into Swedish, and of his fables into Latin and Chinese.

In this regard, it is time that we stop writing about how Monterroso and his work obsessively undermine the genres, laws, canons, and principles of major literature. Although he is famous for the type of concision and wit Calvino praises above, Monterrosos literature always was and will continue to be major. Clean and sharp, rarely harsh or lyrical, his prose is leavened with a dry, ever puckish and conceptual humor. Yet he has never conceded to being any kind of humorist, nor has he fallen into the trap of admitting that serious things are said in jest. In the collections that follow the two included here, and in those that preceded them (two plaquettes from 1952 and 1953), we see the strict precision of a prose uncanny in its ability to suggest compassion for the human condition. It is a prose that offers vivid sights and personal insights, discordant sounds, and extremely rich sensations of body and mind. Monterrosos prose is supple, analytical, full of irony and intricate nuances. What also emerges in his work, especially in the dual collection presented here, is writing that peels away the social veneers that conceal the beast within human beings and reveals all that they have accomplished or undone throughout history.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Complete Works and Other Stories»

Look at similar books to Complete Works and Other Stories. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Complete Works and Other Stories and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.