Carol Birch

Orphans of the Carnival

This is where your lost toys went, the one the dog chewed, the one your mother threw out without asking when you left home, the ones you always wondered about.

The island says: bring me your lost, your scorned, forgotten masses, bring me your maimed and ridiculous, bring me so much as a finger or a toe and Ill take you in. Be you ever so grotesque or beauty sublime, its all the same to me. Everyones allowed in. Doesnt matter who you were or what your story, doesnt matter what state youre in. You couldve been smashed to smithereens, even your broken bits are welcome here.

Theres nothing to the island. The Aztecs made it, many moons ago, long before the white men came. Trees, a stream, a few shacks, an old wooden landing stage. White butterflies hover over red flowers. From time to time a bird whistles, high and thin and querulous. A stream of water makes no sound. The dolls are legion. Strange fruit, they hang on every tree, and the trees crowd close. They hang like bunting on rusty wires running between the trees. They have covered all the walls, inside and out, filled every crack and cranny. The oldest has been here for more than fifty years; the youngest just arrived. The filth is proud.

In the centre of the island, at the centre of a shrine in the middle of a mouldy old shack with the word Museo over the door, a solemn black-haired, blue-eyed girl doll sits like Buddha under a framed colour photograph of the hermit of the island, now dead. She is decked with beads and thin curled ribbons, some faded, some less so, surrounded by the gifts people bring to her, a strange trove of jewellery and holy pictures, sweets and candles, coins and finger puppets, small toys, a Rubiks Cube, a troll, a worn set of Pokemon cards and a pink-haired white pony with large mascaraed eyes. This little girl will want for nothing. She is the little girl who drowned here so long ago, whoever she was. No one knows. It doesnt matter. Little girls are loved and they drown, and there must be comfort for what cant be cured. There must be dolls and shrines and remembrance in the company of a host of faces. Under the corrugated roof, dolls and their parts dangle from the rafters. From ceiling to dirt floor they hang on the flaking whitewashed walls. Spiders have woven furry grey curtains between them, veiling the faces of a few. There is a blunt-faced boy, made by the cobwebs into a strange smudged apparition. Flies hum. Silky eyes, whitened as if by cataracts, peer through trailing grey lianas. Baby dolls, sexy dolls, rag dolls, teen queens, ugly dolls, demon dolls, elvish dolls, dolls in the national costumes of various countries, naked and clothed, suspended, flying like angels. A strung up baby in a blue romper suit hangs broken-necked, half-faced, dirt-encrusted. A gangsters moll in a silk dress is losing her hectic red curls. A tiny face sleeps in the rafters, the underlip tucked in. The closed eyes have the authentic, ancient look of the newborn.

The smell of long-established mould was thick and warm on the air.

Outside, a slight breeze scarcely moved the long leaves and whip-like branches. You could walk round the island in a couple of minutes, but no one did. The endless diversity of decay slowed you down, variations on dollskin: poxed, blistered, burned black, bleached white, patterned elaborately, sometimes geometrically, by weather and the passage of time. Flies crawled on the dolls, gathering like mud in the creases of their clothes. Their eyes spewed bugs. Crazed with a million cracks, mud-splattered, twined with leaves, they grinned with filth-clotted mouths, reached out for a hug, beseeched, pondered, smiled serenely. Most of them were babies.

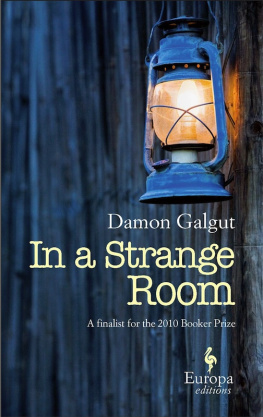

An obscene pink knob poked out of a headless torso. A girl with mud-bedraggled hair and the left leg of another leaned down in greeting, her face a moving black mask of bugs. An old lamp lay in a thicket, a head with black-rimmed eyes poking out of it. A single strand of hair hung down to its chin, and its large blue eyes were innocent and interested. It seemed about to speak. A fat white leg hung on a line. In the root of a tree, a tangle of limbs clung to each other. A clown wore a bonnet. Naked Barbies with hair gone wild had colonised a thin tree, one of them sensibly wearing her sunglasses.

It was a sky burial in slow motion.

The train shook, her brain shook. She flew into the future, dreaming she was lost in a big white house that went on forever, the windows dusty like the windows of the diligence taking her on the first stretch of her journey, from Culiacn to Los Mochis, to get over the mountains and out of Mexico. She saw glimpses of far mountains and miles of scrub, and occasionally a poor peon tramping in rags. Then she was back in her bunk, listening to the sound that had woken her up: a baby crying, far along the train towards New Orleans, a lost thin bleating like a lamb.

Needing privacy, shed paid a few extra dollars to get a berth for the night. The sleeper was dark and cramped, the passage very narrow, people walking up and down it constantly, brushing against the thick hessian curtain shed pulled across in front of her bed. A man in the bunk across the passage snored and snorted and tossed, so close it was indecent, and the clanking and screeching, the jolting and swaying, the dusty coal smell kept her awake. At least she had sheets and they were clean. She huddled down into them with old Yatzi, thinking about the great city, every great promised city, New York, Chicago, Boston, and the people shed meet tomorrow in New Orleans. Yatzis bald wooden head was tucked under her chin.

The whistle was a soul in distress. God but this land was flat and endless. Miles and miles of spreading green, some trees, occasionally a crossroads. The flatness had become a dream verging on nightmare. No one lived here. That there were flat places in the world shed known, but the enormity of it scared her even more than crossing the mountains. Shed been afraid all the way from Culiacn. The first couple of days she kept thinking shed get off at the next stop and go back home. She thought shed be discovered. Theyd be attacked by bandits, robbed. Killed. Two more weeks, slogging higher and higher into her mothers mountains in a smelly wagon she couldnt even get out of to stretch her legs, not till everyone else was asleep, and then only for a brief interlude of wide cool darkness, a quick look up at the frosty stars. The driver and all the passengers thought she was a young girl travelling alone to meet her guardian, veiled because of a vow shed made to Our Lady. Respecting her silence, they left her alone and were kind and helpful whenever they made a stop. Up the mountains, down the mountains, going mad with boredom, sleeping and drifting, jerking awake a hundred times, and with every mile that jolted by feeling more and more unreal, losing all sense of distance, the world a giant carpet unfolding endlessly.

In the morning they pulled into a depot. She was up and dressed and veiled, sitting by one of the small windows. The porter came with bread and coffee. New Orleans was no more than a couple of hours away, he said. The coffee was appalling. She was sick to death of this veil. Shed never had to wear it so much at home. It didnt matter. All these new people shed have to meet, shed be famous, Rates said. She would perform. Theyd flock in their millions. And theyd pay. After New Orleans, New York. Let them goggle. You show them, you show them what you can do, how proud you are, you go out there and let them see you. Cant do it, she thought. Scared. Scared. Have to. Come this far. Who is this Rates anyway?