From a distance, it might have been an army of statues, or of the dead.

Six thousand riders upon a plain of ice and snow, in a land where it seemed that nothing might live. The wind rattled against tall spears like a gale passing through a winter forest, but the horses did not stir, and under close carved helms and thick furred hoods, the mens eyes seemed hollows with no glimmer of life. Seen from afar, one might have thought them a great monument carved to a forgotten king, or an army from a long forgotten war struck down by curse or spell, doomed to stand in place for eternity and wait for a command that would never come.

It was only if one drew close that one could see the little whorls of their breaths frosting before their lips, here and there see a horse toss its head and stamp at the snow. Closer still, and one could hear the impatient whicker and mutter of the horses, more eager for the battle than the men who rode them. They thought only of the rush and joy of the charge, the surge of muscle and hoof, for unlike men they could not imagine their own deaths. Their riders were silent as they looked on the frozen river before them and waited for the Romans to come across the ice.

One spear tilted down in the line, as a warrior laid the weapon to rest across the neck of his mount. The horse gave a snort of protest, for she bore a heavy weight, she and her rider glistening with scales of horn and bone fitted like a second skin. Yet when the rider laid his palms against the haft of the spear and rolled it against the beasts neck, the horses protest went silent, and she leaned into the touch and gave a shiver of pleasure.

The rider beside them shook his head. I think you love that horse more than my wife loves me, Kai.

The first man answered. And why not? My horse is more worthy of love than you are. Shes braver. More handsome, too. He pushed back his hood as he spoke, baring his teeth in a friendly smile.

Laughter then, to break the silence soft, and half choked, but it was there, scattering down the line. Even some of those who could not have heard the jest grinned for a moment, patted their horses, lifted their spears to stretch frozen muscles. For a moment, the army lived once more.

The second rider, Bahadur, cuffed Kai about the head, a slap of leather against bronze, but he answered Kais smile in kind. He leaned forward to speak, close enough for Kai to see every mark of the tattoos on his cheeks, the streaks of grey in his beard. Keep the laughter going, if you can. The others are frightened.

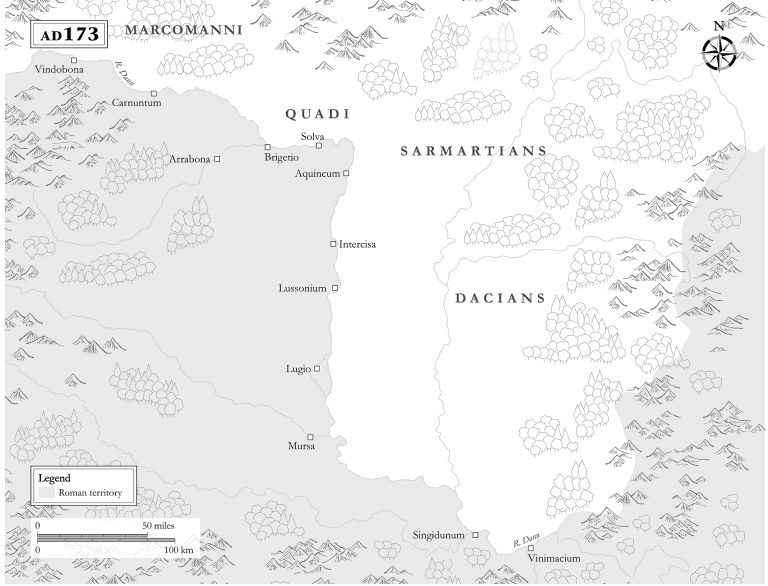

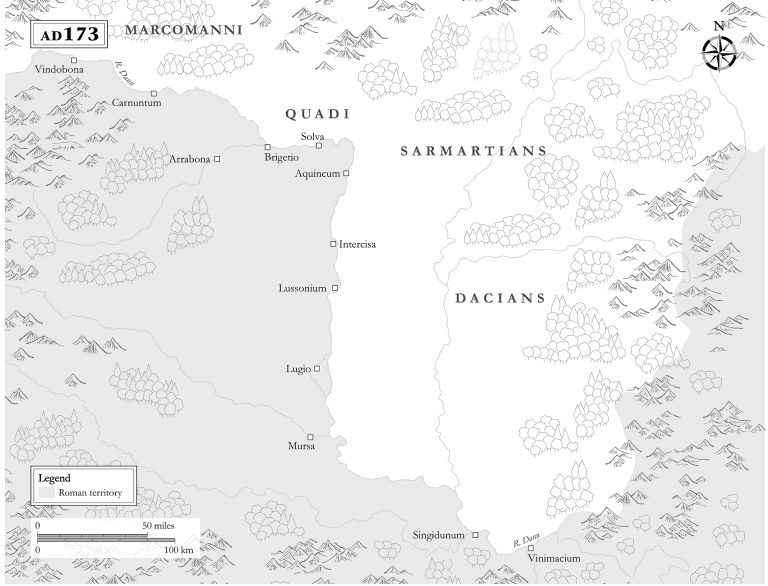

That last word was like a spell, for when it was spoken the air seemed to grow thin and cold as the air of a Carpathian pass. Amongst his people there was nothing worshipped like warriors, no trade thought noble but that of spear and horse, no death counted as sweet save the one found on the point of a blade. Yet only a madman would not be afraid in that moment, for the Sarmatians all knew what was coming across the ice of the Danu.

Kai looked out across the frozen river in front of them, shading his eyes from the spindrift with a gauntleted hand. Little to be seen there, even if the mist had cleared. In summer one might see boats on that river, merchants coming to trade wine and perfume, furs and amber. Or fishermen seeking some blessing from the river god that might feed their families. But the merchants came like thieves across the water, and the fishermen did not care to linger long. For the Danu was a border, and it was more than another country that lay across the water. It was another world.

On the other side of that river, the Roman Empire. A chieftains gold dripping from every womans neck, a prize of iron in every warriors hand. But more important than that, enough wheat and cattle to feed the clans twice over. For the Sarmatians, winter-starved by sickly herds and blighted crops, it was life that was over the water, life that they could almost reach out and touch.

Almost. For across the ice the enemy waited for them. An enemy whose name was spoken as a warning to children, a bitter curse to a rival clan.

Kai had seen that enemy broken in battle, their general cut open while he still lived, left pinned out and screaming for the carrion birds to butcher as a warning to his people. Still, they had come back. Another tribe, the Marcomanni, had burned fort and city and carried the fight almost to within sight of Rome itself, and the Legions had returned undaunted. A few years before, the gods had cursed the Romans with a plague that had piled the corpse fires high, had murdered entire armies, murdered so many that it seemed there could be no man left alive west of the Danu. Yet they were there in their forts, scarce two miles away, somewhere across the ice. For those were the men that it seemed not even the gods could kill.

We are the last ones left, said Kai.

What?

The last people still fighting Rome. The Marcomanni are kingless. The Quadi pledged to Rome after the miracle of the rain. The Dacians Bahadur muttered a foul curse at that name, and Kai had no need to speak further of them. There are none but us left to fight. What do you think that means?

Beneath his cloak and helm, Bahadurs face was unreadable. The touch of light on his eyes was it anger or grief at the words that Kai spoke, words that danced at the edge of doubt?

That we shall have to win here today, the older man said, if we are to eat this winter. If we are to be free. What do you think that it means?

That our grandfathers should never have left Scythia. That our people should have stayed upon the Sea of Grass to the east.

They would have come for us there, too. A little later, that is all.

Better that we fight them now, said Kai. Or our children would have to fight them instead.

A little cry at that not from Bahadur, but from the rider behind him, a boy who huddled on his horse and shivered and wept. Too young for the warband and drowning in his armour, it should have been another summer at least before he was asked to set his spear in the charge. But the ranks were filled with those like him greyhaired men who could scarce hold their spears, boys who should have been herding sheep out on the steppe. It was Bahadurs son, Chodona, who shamed himself with those tears, and Bahadur put his arm about the boy and drew him close, whispering the wordless charms against fear that father might speak to his child.

Watching them, Kai felt the cowards hope that the Romans would not come. Let them stay in their forts across the water, so that the boy might live to become a man.

But already, it was too late. For a sound was echoing across the river, coming through the mist. At first Kai thought it the bark and chatter of the ice, the echo of a distant storm that boomed and blew across the open land. But soon there was no mistaking what it was.

Mothers whispered stories of that sound to children around the campfire at night. Warriors spoke of hearing it for the very first time, as though a great monster had crawled up from the pits of another world to scuttle across the ground on ten thousand feet. And everywhere that it moved, it left the dead piled high, too many to honour and send to the next world with iron and gold. And for those that lived, a different kind of death. A death of submission, and slavery.

The stamping tread of an army moving as one. The sound of the Legion on the march.

It struck the horsemen like a curse. The quiet words of encouragement, the boasts and the black-humoured jokes all went silent. The riders hunched their cloaks about them, and even the proud horses fell quiet. They had heard that sound many times before. Hard-fought victories, bitter defeats, retreats that had scattered them across steppe and plain. And in victory or defeat, nothing changed. Still the Legion walked on.