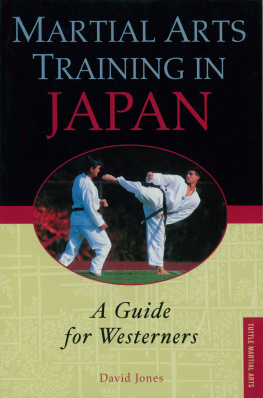

ABOUT THE BOOK

Beginning students in Japanese martial arts, such as karate, judo, aikido, iaido, kyudo, and kendo, learn that when they are in the dojo (the practice space), they must don their practice garb with ritual precision, address their teacher and senior students in a specific way, and follow certain unwritten but deeply held codes of behavior. But very soon they begin to wonder about the meaning behind the traditions, gear, and relationships in the dojo.

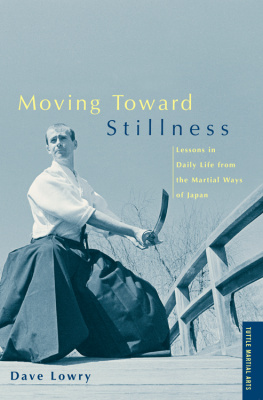

In this collection of lively, detailed essays, Dave Lowry, one of the most well-known and respected swordsmen in the United States, illuminates the history and meaning behind the rituals, training costumes, objects, and relationships that have such profound significance in Japanese martial arts, including

- the dojo space itself

- the teacher-student relationship

- the act of bowing

- what to expectand what will be expected of youwhen you visit a dojo

- the training weapons

- the hakama (ceremonial skirt) and dogi (practice uniform)

- the Shinto shrine

Authoritative, insightful, and packed with fascinating stories from his own experience, In the Dojo provides a wealth of information that beginning students will pore over and advanced students will treasure.

DAVE LOWRY is an accomplished martial artist, calligrapher, and writer. He is the restaurant critic for St. Louis Magazine and writes regularly for a number of magazines on a wide variety of subjects, many of them related to Japan and the Japanese martial arts. He is the author of numerous books including Autumn Lightning: The Education of an American Samurai, Sword & Brush: The Spirit of the Martial Arts, Clouds in the West: Lessons from the Martial Arts of Japan, and The Connoisseurs Guide to Sushi.

Sign up to learn more about our books and receive special offers from Shambhala Publications.

Or visit us online to sign up at shambhala.com/eshambhala.

IN THE DOJO

A GUIDE TO THE RITUALS AND ETIQUETTE OF THE JAPANESE MARTIAL ARTS

DAVE LOWRY

WEATHERHILL

Boston & London

2012

WEATHERHILL

An imprint of

Shambhala Publications, Inc.

Horticultural Hall

300 Massachusetts Avenue

Boston, Massachusetts 02115

www.shambhala.com

2006 by Dave Lowry

Cover design by Gopa & Ted2, Inc.

Cover art: Dragon and Tiger, Obaku Sokuhi (16161671), courtesy of the Gitter-Yelen Collection.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Lowry, Dave.

In the dojo: a guide to the rituals and etiquette of the Japanese martial arts/Dave Lowry.1st ed.

p. cm.

eISBN 978-0-8348-2436-2

ISBN 978-0-8348-0572-9 (pbk.: alk. paper)

1. Martial artsJapan. I. Title.

GV1100.77.A2l64 2006

796.80952dc22

2006019959

FOR DIANE,

though what she wanted with it

I am still not sure.

To see as far as one may and to feel the great forces that are behind every detail... to hammer out as complete and solid a piece of work as one can, to try to make it first rate, and to leave it unadvertised.

OLIVER WENDELL HOLMES

CONTENTS

T he writer writes, if he expects to be read, for an audience. As he puts the words down on the page, he hears them being read. He wonders how they will sound, if the reader will understand his point, if they will follow his line of reasoning or the gist of his topic. He also hears, to some extent, the words of the reviewer, the critic who will write about his book. (He hopes they will write about it at least. To be critically ignored cuts a deeper wound than to be panned.) As I wrote this book I sometimes heard the critic in my head, and sometimes some of the readers there as well, all asking the same question: Does this guy, literarily speaking, ever shut up? Does he ever run out of things to say about the most obscure aspects of a subjectthe Japanese martial arts and Waysthat is itself about as marginal in our society as a subject can be and still have a presence on the map? As I wrote, I had the distinct feeling from time to time that I was that fellow sitting next to you on a cross-country flight or on some bar stool. The one going on and on and on about something or other until your thoughts turned to homicide and then, in increasing despair, to suicide.

In fact, at least one published critic has said thatdo I ever shut up?more or less, about another of my books. I had described in it an omamori, a talisman offered for sale at nearly every Shinto shrine in Japan. Why had I felt the need to give the name for these in the book, the reviewer wondered. He had, he explained in his review, been given one recently by someone returning from Japan. It had been described to him by the giver as a doodad. And he gave every indication this was a sufficient description for him and that my dilation on omamori was, at best, tedious. The book you are holding right now is not for that reviewer. Or readers like him. That is not to disparage him. Or them. The world is full of such people. In certain realms I am among them. Someone, for instance, will ask if I have seen the latest model of some kind of automobile and I will have to answer, honestly, that I havent the vaguest idea whether I have seen it or not. There are two kinds of cars for me: those that go, and those that do not. I prefer the former and if I am hard-pressed I can describe the color and make a reasonable guess about the number of doors it has. But thats about it. In other matters, however, I am utterly captured by the details of things. I wish to know not only what they are, but how they work, why they developed as they did, and what is the history, pedigree, and nomenclature surrounding them. A friend wrote me not long ago; he had come across the word lamentation as a term of venery. What group of things was described as a lamentation? he wrote me, expecting me to know. (To my own credit, I did. Its swans.) More recently, I spent some time on the campus of Kenyon College, deep in the heart of Ohios Amish country and, while perusing the colleges justly fabled bookstore, I came across a field guide to Amish buggies. Identical for all practical purposes to the casual observer, each order and each community has its own, distinctive styles. And so of course for the remainder of my stay at Kenyon, I spent part of each evening reading the field guide and part of each day happily identifying the different kinds of buggies that are regularly driven through the tree-lined streets of that beautiful and pastoral campus.

Having spent at least two-thirds of my life around the budo, the Japanese combative arts and Ways, my penchant for learning the minutiae of things has not surprisingly blossomed there. I was fortunate; one of my first teachers was Japanese and there were, coming and going through his house on a regular basis, a number of Japanese either living in the U.S. as expatriates or visiting the States, and most of them were amenable to fielding the endless questions I asked. The answers they provided often led to other questions. The questions I had and the answers I received were the impetus for this book. As I continued my education in the budo, I began to make two observations consistently. The first was that there were any number of titles written to explain the combative disciplines of Japan to the absolute beginner. Introductory texts about the history and technical details of karate-do, aikido, kendo, judo, and so on, are all over the place. Some are authoritative and well done. Others are derivative, often repeating the same information (or misinformation) that has come from earlier books. (It is an instructive lesson in sloppy scholarship, for example, to trace the fact that Okinawan karate was devised by the peasants of the Ryukyuan archipelago in order to allow them, unarmed, to take on and kill their despotic Japanese samurai overlords. The tale has been repeated in so many books that it has achieved a life of its own and is, in all probability, being repeated right now in some karate class somewhere in the world. Similarly, that the short sword carried by the samurai found its principal use as a means of self-immolation when the necessity presented itself has become another such fact.)

Next page