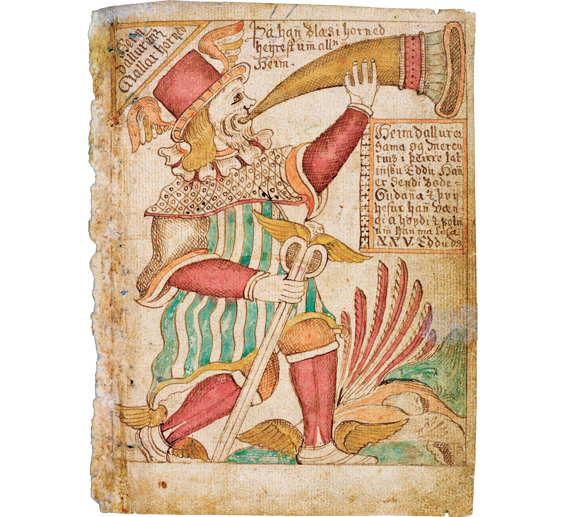

This is an illustration from an Icelandic manuscript of the 18th century. Here the god Heimdall is blowing Gjallarhorn to summon the Aesir to a meeting .

AFTERWORD

T he first recorded versions we have of the Norse myths are in Icelandic sagas that date from around A.D . 1180. But somewhere around 1225 the Icelander Snorri, son of Sturla, gave us a major work called the Snorra Edda, also known as Prose Edda. Most of our ideas about Norse mythology today are based on that work.

Many of the Norse texts we have are examples of what is called skaldic poetry, which would have been performed at court events by skilled poets who wrote their own verse. Skaldic poetry obeyed complex rules about internal rhyme, patterns of alliteration, meter, and other issues of stress. The result was often a syntax so convoluted that sometimes scholars are unsure what is actually meant by a given verse.

Snorri offers stories and poems, as well as a poetry handbook that explains the structure of the poems and a prologue that gives a somewhat historical framework for the myths. While Snorri was Christian, he treats the pagan mythology with respect. Some of the Icelandic sagas were probably written by Snorri, but others were written after his death, well into the 14th century. The Prose Edda was preserved in the manuscript called Codex Regius 2367, 4.

Alongside Snorris work is another collection, called the Poetic Edda. It is preserved in the manuscript Codex Regius 2364, 4. It contains a collection of poems in a much more relaxed form, the style of which has become known as Eddic. These poems were anonymous and performed by all sorts of people on all sorts of occasions; they are clear and easily comprehensible.

As I was writing this book, I consulted translations of both works and I came across a number of inconsistencies between the mythological tales. The inconsistencies I found are of three types, and the way I handled them in this book varies based on the type.

One type is logical inconsistency. Since the reader is very likely to pick up on this, I face it head-on. In The Gods Take Revenge Loki is bound up till the conflagration of Ragnarok. But Loki is a shape-shifter. He could easily have turned into a flea and escaped. The sources I consulted did not address this inconsistency. So I mention it at the end of the chapter as a question for the reader. Other times characters behave as though they dont know the future, when, in fact, they should. In Death by Blunder, for example, Loki disguises himself as an old woman and asks Frigg if any object in the cosmos failed to take the oath not to harm Balder. Frigg knows the future, so she should either not answer Loki or be tied up in knots by not being able to stop herself from answering him, fully aware of what hell do with the information. Instead, she seems to simply answer him as though she has no idea what will come of it. So I question her behavior right there in the chapter.

A second problem is inconsistencies of facts. For example, in Idunns Apples Odin and Loki and Hoenir are hungry and cant get meat to cook over an open fire because an eagle has put a magic spell on it. Odins mouth waters for this meat. But Odin is supposed to live on wine alone. There was no way to address this inconsistency without breaking dramatic momentum. In my retelling, therefore, I simply dont mention Odins feelings about the meat in order not to confront the reader with a conflict that to me seems irrelevant. For another, Odins brothers are called Vili and Ve in the Poetic Edda, but later we find that three gods brought humans to life: Odin, Hoenir, and Lodur. In the Prose Edda those three gods are said to be sons of Bor. But nowhere does it say that Bor had more than three sons. I didnt want to leave out the names of the three gods who were so important to the origin of humans, so I simply said the number of gods had grown and I didnt bring up whether these particular three gods were brothers or not. Likewise, one of Odins sons and one of Lokis sons share the name Vali, and scholars point out potential confusions between the two. But I simply left both gods with the name given them in the Poetic Edda and made sure to make it clear each time I discussed them which one was involved. And, finally, the name Fjalar in this book belongs to a dwarf and to a rooster. Actually, it was a common name in Norse mythology for any deceiver, so it might not have been a name at all but an epithet (like naming someone Liar).

A third kind of inconsistency involves time. When Loki is insulting everyone at the feast in the huge hall in The Gods Take Revenge, he includes in his harangue Bragi, the god of poetry. Soon after this, Kvasir helps to trap Loki. But Bragi is not born until after Kvasirs death. Here I resolve the issue by simply not mentioning Bragi in the list of gods that Loki insults, since Bragi does not take any action of note at this feastso no inconsistency slaps the reader in the face. Another possible inconsistency is in Frey & Gerd, when Skirnir offers Gerd the ring Draupnir if shell marry Frey. This is based on the poem Skrnisml of the Poetic Edda, and it is unclear where this event fits among the others timewise. To me, for dramatic effect, this story should immediately follow the story of Skadi and Njord, so thats where I put it. But the ring presents a problem. The dwarf Brokk gave Draupnir to Odin. At Balders funeral, Odin, distraught with grief, threw it into the blazing ship that was his sons coffin. But later, when Hermod went to Hel to try to win Balders freedom, Balder gave Draupnir to Hermod and asked him to return it to Odin. I dont know how it came to be in Skirnirs hands at any point. But, perhaps, if Skirnir has Draupnir, then Loki is dead. Yet at this point in my retelling, Loki is still alive. I try to allay any confusions the reader might have by saying its anyones guess how the ring fell into Skirnirs hands.

This is an illustration from an Icelandic manuscript of the 17th century. Here we see Valhalla on one side and Jormungand on the other .

This third kind of inconsistency is interesting. I have found time inconsistencies repeatedly in mythologies of many cultures, including those of ancient Greece and ancient Egypt. This may be partially due to the fact that different people wrote down the different tales and at different times, and may not have been aware of (or cared to dovetail with) what the others wroteleading to inconsistencies. And certainly, traditional stories often have multiple variants. But it might also suggest that mythologies sometimes do not adhere to linear chronology. Why cant time simply fold back on itself, especially in a world riddled with magic?

DONNA JO NAPOLI is a professor of linguistics at Swarthmore College, the mother of five and grandmother of four, and the author of more than 70 books for children and young adults, including National Geographics Treasury of Greek Mythology and Treasury of Egyptian Mythology . While her undergraduate major was mathematics and her graduate work was in linguistics, she has a profound love of mythology, folklore, and fairy tales. This is her third mythology treasury for National Geographic. Her website is donnajonapoli.com.

CHRISTINA BALIT is a graduate of the Chelsea School of Art and the Royal College of Art, London. An award-winning dramatist and illustrator, Christina has painted more than 20 childrens books, including Blodin the Beast by Michael Morpurgo, Zoo in the Sky, The Planet Gods, The Lion Illustrated Bible for Children, National Geographics Treasury of Greek Mythology , and National Geographics Treasury of Egyptian Mythology . Her authored titles include Escape From Pompeii, Atlantis: The Legend of the Lost City , and An Arabian Home . Her plays include Woman With Upturned Skirt, The Sentence , and Needle (winner of the Brave New Role Award).