THE BODHISATTVA IDEAL

SANGHARAKSHITA

THE BODHISATTVA IDEAL

WISDOM AND COMPASSION IN BUDDHISM

WINDHORSE PUBLICATIONS

Published by Windhorse Publications Ltd

169 Mill Road

Cambridge

CB1 3AN

United Kingdom

www.windhorsepublications.com

Sangharakshita 1999

Reprinted 2008, 2010

Electronic edition 2013

The right of Sangharakshita to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

Cover design by Dhammarati

Illustrations by Varaprabha

The cover shows the Bodhisattva Padmapni, Ajanta Caves

Coutsesy of the ITBCI School, Kalimpong

The publishers acknowledge with gratitude permission to quote extracts from the following:

p.53 D.T. Suzuki Outlines of Mahyna Buddhism, Schoken, New York 1970.

p.169 A.F. Price and Wong Mow-Lam (trans.), The Diamond Sutra and the Sutra of Hui-Neng, Shambhala, Boston 1990.

p.176 s.Gam.po.pa, The Jewel Ornament of Liberation, H.V. Guenther (trans.), Shambhala, Boston 1986

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data:

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Paperback ISBN: 978 1 899579 20 4

ebook ISBN: 978-1-909314-10-8

Since this work is intended for a general readership, Pali and Sanskrit words have been transliterated without the diacritical marks that would have been appropriate in a work of a more scholarly nature.

A Windhorse Publications ebook

Windhorse Publications would be pleased to hear about your reading experiences with this ebook at

References to Internet web sites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor Windhorse Publications is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

Contents

About the Author

Sangharakshita was born Dennis Lingwood in South London, in 1925. Largely self-educated, he developed an interest in the cultures and philosophies of the East early on, and realized that he was a Buddhist at the age of sixteen.

The Second World War took him, as a conscript, to India, where he stayed on to become the Buddhist monk Sangharakshita. After studying for some years under leading teachers from the major Buddhist traditions, he went on to teach and write extensively. He also played a key part in the revival of Buddhism in India, particularly through his work among the most socially deprived people in India, often treated as untouchables.

After twenty years in India, he returned to England to establish the Friends of the Western Buddhist Order in 1967, and the Western Buddhist Order in 1968. A translator between East and West, between the traditional and the modern, between principles and practices, Sangharakshitas depth of experience and clear thinking have been appreciated throughout the world. He has always particularly emphasized the decisive significance of commitment in the spiritual life, the paramount value of spiritual friendship and community, the link between religion and art, and the need for a new society supportive of spiritual aspirations and ideals.

The FWBO is now an international Buddhist movement with over sixty centres on five continents. In recent years Sangharakshita has been handing on most of his responsibilities to his senior disciples in the Order. From his base in Birmingham, he is now focusing on personal contact with people, and on his writing.

EDITORS PREFACE

God once looked into nothingness and made something come to be.... [The] Buddha ... saw that the world had always been, and he, in his wisdom, found a way to allow some of it to stop. His gift to us his act of greatest compassion was to teach us that way. Who is to say that this is finally any less loving than the Christian drive to mimic Gods sublime generosity in a never-ending round of action and creativity?

The fear, or the conviction, that Buddhism is selfish seems to be one of the greatest obstacles to the reception of the Buddhas teaching in the West. It may be based on a vague, and mistaken, sense that the most evident aspects of Buddhist activity meditation, ritual, the study of ancient texts serve no purpose in the real world, do nothing to help this troubled planet. Buddhists rightly advocate the need for reflection before action; like most witticisms, that phrase Dont just do something, sit there has some point to it, although the virtues of fearlessness and prompt action are in fact no less part of the Buddhist tradition. But while the charge of selfishness seems ironic, given the more obvious selfishness of so many of the other options our society offers, the fear is a reasonable one.

That wisdom and compassion are inseparable aspects of Enlightenment is easy to say, but the working out of that truth has shaped Buddhist history and practice. If the desire for wisdom takes us, in a sense, out of the world, the force of compassion that arises with the development of true wisdom brings us straight back into it. And in practice we need to work on developing both at the same time. Without at least the first stirrings of compassion, a life lived in the name of Buddhism can indeed become as selfish as the worst excesses of the life, the world, that it purports to have the aim of transforming.

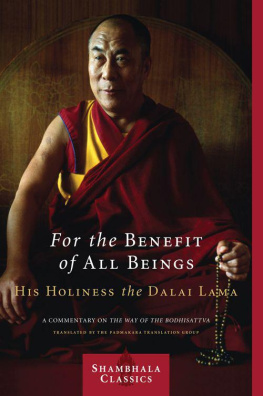

What has become known as engaged Buddhism is seen by many Western Buddhists as the only way forward. To focus this aspiration, it seems time for an unequivocal reassertion of the heroic, other-regarding, compassionate nature of the ideal Buddhist: not otherworldly, but this-worldly. We do see people who exemplify these qualities the Dalai Lama is the most famous, but there are many others. And in terms of Buddhist tradition, the inspiration we need already exists: in the form of the Bodhisattva the wise, compassionate, tirelessly energetic, endlessly patient, perfectly generous, and completely skilful ideal Buddhist beloved of the Mahyna tradition. What we also need is a clear and pragmatic understanding of how to begin to approach such a lofty ideal.

Throughout Buddhist history there have been times when the need for a restatement of the Buddhist ideal has been recognized. It was such a period of revalorization that led to the emergence of what Sangharakshita has called one of the sublimest spiritual ideals that mankind has ever seen: the Bodhisattva ideal. The somewhat obscure origins of this ideal, and of the school of Buddhism that came to call itself the Mahyna, the great way, have been the focus of much recent scholarship. In particular, it has been important to sort out whether and in what sense the Arhant ideal of early Buddhist tradition was equivalent to the Bodhisattva ideal which emerged in response to it. The Mahynists came to refer to those who rejected the new Mahyna scriptures as following the Hnayna, the lesser way, a pejorative designation that has needed to be reassessed.

While touching on the relationship of the Bodhisattva ideal to earlier Buddhist ideals, this book especially considers the origin of the Bodhisattva ideal in broad, almost mythical terms: in terms not just of the tension between the human tendency towards self-interest and our innate feeling for our kinship with other living beings, but also of our need to honour our own spiritual development, balanced against our need to respond to the needs of others.

Sangharakshitas acquaintance with the Bodhisattva ideal began, like so much in his life, with a book. Having, at the age of sixteen, read two Buddhist texts renowned for their sublime wisdom the Diamond Stra and the Stra of Hui Neng and realized that he was a Buddhist, one of the next Buddhist works he happened upon (and there werent so many around in England in the 1940s) was an extract from a work equally renowned for the sublimity of its compassion, the