Shambhala Publications, Inc.

Horticultural Hall

300 Massachusetts Avenue

Boston, Massachusetts 02115

www.shambhala.com

1997, 2006 by the Padmakara Translation Group

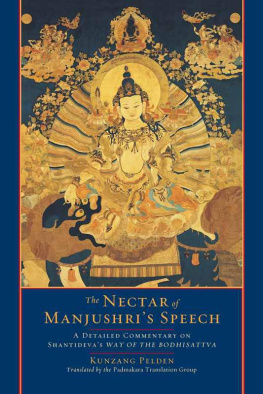

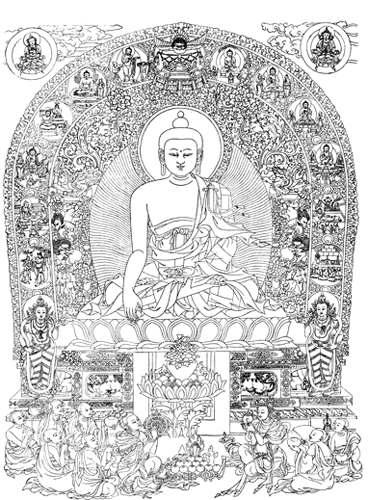

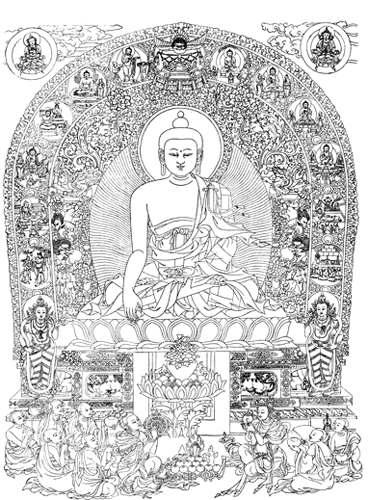

Cover art: Seated Guanyin Bodhisattva . Northern Song Dynasty (9601127).

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri (Purchase: Nelson Trust) 34-10.

Photograph by Robert Newcombe.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Second edition, revised

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Santideva, 7th cent.

[Bodhicaryavatara. English.]

The way of the Bodhisattva: a translation of the Bodhicharyavatara / Shantideva; translated from the Tibetan by the Padmakara Translation Group; foreword by the Dalai Lama.Rev. ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

eISBN 978-0-8348-2565-9

ISBN 978-1-59030-388-7 (pbk.: alk. paper)

1. Mahayana BuddhismDoctrinesEarly works to 1800. I. Bstan-dzin-rgya-mtsho, Dalai Lama XIV, 1935 II. Padmakara Translation Group III. Title.

BQ3142.E5P33 2006

294.385DC22

2006014801

Contents

The Padmakara Translation Group gratefully acknowledges the generous support of the Tsadra Foundation in sponsoring the preparation of this revised edition.

The Bodhicharyvatra was composed by the Indian scholar Shntideva, renowned in Tibet as one of the most reliable of teachers. Since it mainly focuses on the cultivation and enhancement of bodhichitta, the work belongs to the Mahyna. At the same time, Shntidevas philosophical stance, as expounded particularly in the ninth chapter on wisdom, follows the Prsagika-Madhyamaka viewpoint of Chandrakrti.

The principal focus of Mahyna teachings is on cultivating a mind wishing to benefit other sentient beings. With an increase in our own sense of peace and happiness, we will naturally be better able to contribute to the peace and happiness of others. Transforming the mind and cultivating a positive, altruistic, and responsible attitude are beneficial right now. Whatever problems and difficulties we may have, we can thereby face them with courage, calmness, and high spirits. Therefore, it is also the very root of happiness for many lives to come.

Based on my own little experience, I can confidently say that the teachings and instructions of the Buddhadharma and particularly the Mahyna teachings continue to be relevant and useful today. If we sincerely put the gist of these teachings into practice, we need have no hesitation about their effectiveness. The benefits of developing qualities like love, compassion, generosity, and patience are not confined to the personal level alone; they extend to all sentient beings and even to the maintenance of harmony with the environment. It is not as if these teachings were useful at some time in the past but are no longer relevant in modern times. They remain pertinent today. This is why I encourage people to pay attention to such practices; it is not just so that the tradition may be preserved.

The Bodhicharyvatra has been widely acclaimed and respected for more than one thousand years. It is studied and praised by all four schools of Tibetan Buddhism. I myself received transmission and explanation of this important, holy text from the late Kunu Lama, Tenzin Gyaltsen, who received it from a disciple of the great Dzogchen master, Dza Patrul Rinpoche. It has proved very useful and beneficial to my mind.

I am delighted that the Padmakara Translation Group has prepared a fresh English translation of the Bodhicharyvatra . They have tried to combine an accuracy of meaning with an ease of expression, which can only serve the texts purpose well. I congratulate them and offer my prayers that their efforts may contribute to greater peace and happiness among all sentient beings.

T ENZIN G YATSO

THE FOURTEENTH DALAI LAMA

17 October 1996

When the first edition of The Way of the Bodhisattva was published in 1997, it was stated that the commentary of the Nyingma master Khenpo Kunzang Pelden (18721943) had been consulted for the elucidation of difficult passages. At the time, a translation into English of that long and important work was no more than a pious dream. Now, after a wait of almost ten years and many intervening projects, this task has been completed; and the careful reading and study of the text that it involved prompted us to revisit and overhaul our original version of The Way of the Bodhisattva , correcting errors and, where possible, making it a tauter, more literal, reflection of the Tibetan original. We hope that we have been able to rectify the perhaps undue freedom of expression in the earlier rendering that led some of its readers to question its accuracy, while at the same time maintaining and improving on the stylistic features that others found attractive. It is a rare thing in the publishing business to have the opportunity to amend past work and to remove, or at any rate diminish, its more obvious blemishes; and we are extremely grateful to Emily Bower and the staff at Shambhala Publications for being willing to produce this new edition.

Since 1997, several other translations of the Bodhicharyvatra have appeared in English. The first, published just as The Way of the Bodhisattva was going to press, was made by Kate Crosby and Andrew Skilton directly from the surviving Sanskrit text. This was followed shortly afterward by the translation of Vesna and Alan Wallace, made also from the Sanskrit but with reference to the Tibetan, and with the Tibetan variants given in footnotes. Later, in 2003, a version was published by Neil Eliott based in the explanations of Geshe Kelsang Gyatso. Most recently, another rendering (printed and circulated at the time of His Holiness the Dalai Lamas teaching on the Bodhicharyvatra in Zurich, 2005) was produced by Alexander Berzin, mainly from the Tibetan but revised and corrected in light of the Sanskrit. Finally, yet another project to translate Shntidevas root text and the commentary by Kunzang Pelden, accompanied by the inestimable explanations of Khenpo Chga of Shri Simha College in Kham, was inaugurated in 2002 by Andreas Kretschmar, who, in an act of great and openhanded generosity, has made his as yet uncompleted work freely available on the Internet. All these translations are of the greatest interest, and although, for our interpretation, we have followed Kunzang Pelden in all things, in preparing this revised edition, we have diligently compared our work with the versions just mentioned and gratefully acknowledge the help that they have given us.

The appearance of translations of the Bodhicharyvatra made from the Sanskrit, side by side with others made from the Tibetan, calls into question with renewed force the desirability of translating what is itself a translation, when a manuscript of the text still exists in the original language. This is closely connected with another question, which concerns the relative merits of study (and by extension, translation) within the environment of secular Western scholarship as contrasted with the traditional setting of a Tibetan monastic college and a teacher-disciple relationship. These two approaches differ considerably both in method and objective. The Buddhologist of Western academia aims, through the examination of texts, archaeological evidence, and so on, to arrive at a scientifically objective understanding of a religious culture. This is viewed, from outside, as an essentially anthropological phenomenon, the beliefs and practices of which are described and classified within a discipline that consciously distances itself from religious allegiance and practice. Buddhists, on the other hand, study the sacred texts as part of a spiritual discipline, intending or at least aspiring to implement the teachings they contain. And to that end, they attach an equal importance not only to the origins and authorship of the texts, but also to the living tradition of explanation and practice that has preserved them into the present age. These two approaches obviously overlap, in the sense that textual accuracy and correct interpretation are of prime importance for both. Nevertheless, they diverge in important respects; and it is important to recognize the difference between independent, academic scholarship, with its essentially humanistic interest in texts, as compared with the allegiance to a tradition of spiritual training: detached erudition on the one hand, committed involvement on the other.

Next page