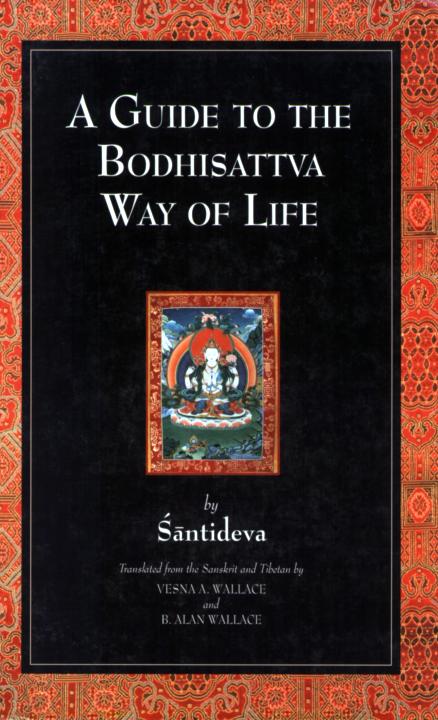

A GUIDE TO THE

BODHISATTVA WAY OF LIFE

(Bodhicaryavatara)

A GUIDE TO THE

BODHISATTVA WAY OF LIFE

(Bodhicaryavatara)

by

Santideva

Translated from the Sanskrit and Tibetan by

Vesna A. Wallace

and

B. Alan Wallace

Table of Contents

Chapter 1: 17

Chapter 23

Chapter 33

Chapter 39

Chapter 47

Chapter 61

Chapter 77

Chapter 89

Chapter 115

Chapter 137

Dedicated to the memory of Venerable Geshe Ngawang Dhargyey

Preface

and his recent comprehensive work entitled The World of Tibetan Buddhism frequently cites this text. The Bodhicaryavatara has also been a widely known and respected text in the Buddhist tradition of Mongolia, and it was the first Buddhist text translated into classical Mongolian from Tibetan by Coiji Odser in 1305.

Although the Bodlhicarydvntara has already been translated several times into English, earlier translations have been based exclusively on either Sanskrit versions or Tibetan translations. To the best of our knowledge, no earlier translation into English, including the recent translation by Kate Crosby and Andrew Skilton, has drawn from both the Sanskrit version and its authoritative Sanskrit commentary of Prajnakaramati as well as Tibetan translations and commentaries. Our present translation is based on two Sanskrit editions, namely, Louis de la Vallee Poussin's edition (1901) of the Bodhicaryavatara and the Panjika commentary of Prajnakaramati, and P. L. Vaidya's edition (1960) of the Bodhicaryavatara and the Panjika commentary; and it is also based on the Tibetan Derge edition, entitled the Bodhisattva- caryavatara, translated by Sarvajnadeva and deal brtsegs. We have also consulted two Tibetan commentaries to this work: sPyod 'jug rnam bshad rgyal sras 'jug ngogs by rGyal tshab dar ma rin chen and Byang chub sems pa'i spyod pa la 'jug pa'i 'grel bshad rgyal sras rgya mtsho'i yon tan rin po the mi zad jo ha'i bum bzang by Thub bstan chos kyi grags pa. As becomes apparent throughout the text, contrary to popular assumption, the recension incorporated into the Tibetan canon is significantly different from the Sanskrit version edited by Louis de la Vallee Poussin and P. L. Vaidya. This would seem to refute the contention of Crosby and Skilton that the canonical Tibetan translation by Blo ldan shes rab was based on the Sanskrit version available to us today. Moreover, pronouncements concerning which of the extant Sanskrit and Tibetan versions is truer to the original appear to be highly speculative, with very little basis in historical fact. This translation attempts to let these versions speak for themselves-as closely as the English allows-leaving our readers to make their own judgments concerning the degree of antiquity, authenticity, and overall coherence of the Sanskrit and Tibetan renditions of Santideva's classic treatise.

In terms of our methodology, we have primarily based our translation on the Sanskrit version and its commentary, though we have always consulted the Tibetan translation and its commentaries. Thus, the main text constitutes a translation of both the Sanskrit and Tibetan versions where they do not differ in content. However, in those verses where the Tibetan differs significantly from the Sanskrit, we have included English translations of the Tibetan version in footnotes to the text. Explanatory notes drawn from the Panjika commentary and other sources have also been given in footnotes to the text. Many of the Sanskrit verses of this text are concise and at times cryptic, and they often entail complex syntax. Thus, at times we were forced to take certain freedoms in our translation in order to make the English intelligible.

We hope that this translation will contribute to the greater understanding and appreciation of this classic treatise by Santideva, and that it will inspire others in the further study of this text and other works attributed to this great Indian Buddhist contemplative, scholar, and poet.

Vesna A. Wallace

B. Alan Wallace

Half Moon Bay, California

July 1996

Introduction

A Brief Biography of Santideva

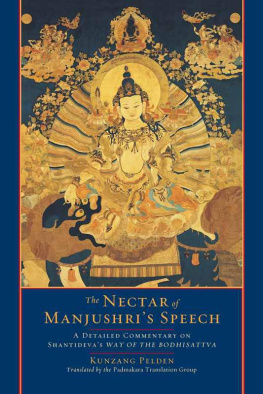

But on the verge of his coronation, Manjuri, a divine embodiment of wisdom, and Tara, a divine embodiment of compassion, both appeared to him in dreams and counseled him not to ascend to the throne. Thus, he left his father's kingdom, retreated to the wilderness, and devoted himself to meditation. During this time, he achieved advanced states of sanladhi and various siddhis, and from that time forward he constantly beheld visions of Manjusri, who guided him as his spiritual mentor.

After this sojourn in the wilderness, he served for awhile as minister to a king, whom he helped to rule in accordance with the principles of Buddhism. But this aroused jealousy on the part of the other ministers, and Santideva withdrew from the service of the king. Making his way to the renowned monastic university of Nalanda, he took monastic ordination and devoted himself to the thorough study of the Buddhist sutras and tan tras. It was during this period that he composed two other classic works: the Siksasamuccaya and the Sutrasamuccaya. But as far as his fellow monks could see, all he did was eat, sleep, and defecate.

it is said that he rose up into the sky. Even after his body disappeared from sight, his voice completed the recitation of this text.

Different versions of this work were recorded by his listeners, and they could not come to a consensus as to which was the most accurate. Eventually, the scholars of Nalanda learned that Santideva had come to dwell in the city of Kaliriga in Triliriga, and they journeyed there to entreat him to return to the university. Although he declined, he did tell them where to find copies of his other two works, and he told them which of the versions of the Bodhicaryavatara was true to his words.

Thereafter, Santideva retreated to a monastery in a forest filled with wildlife. Some of the other monks noticed that at times animals would enter his cell and not come out, and they accused him of killing them. After he had demonstrated to them that no harm had come to these creatures, he once again departed, despite the pleas of his fellow monks to remain. On this and many other occasions, Santideva is said to have displayed his amazing siddhis. From this point on, he renounced the signs of monkhood and wandered about India, devoting himself to the service of others.

Contextualization of the Bodhicaryavatara

At the outset of this treatise, Santideva denies any originality to his work, and indeed its contents conform closely to the teachings of many of the Mahayana sutras. However, the poignancy and poetic beauty of his work belie his disavowal of any ability in composition. Due to the terse nature of his Sanskrit verses, the aesthetic quality of his treatise has been very difficult to convey in English. Therefore, in our translation, where necessary we have opted for accuracy of content over poetic quality. We hope this does not obscure the fact that the Bodliicarttavatara stands as one of the great literary and religious classics of the entire Buddhist tradition.

The thematic structure of this work is based on the six perfections of generosity, ethical discipline, patience, zeal, meditation, and wisdom, which provide the framework for the Bodhisattva's path to enlightenment. The first three chapters discuss the benefits of hodhicitta, the Spirit of Awakening that motivates the Bodhisattva way of life, and explain the means of cultivating and sustaining this altruistic aspiration. Those topics lay the foundation of the perfection of generosity.