Print-format edition for this eBook was revised and expanded after thirty-two years with a new foreword by the editor, Anthony Blake.

First print edition published in the United States of America in 1983 by Samuel Weiser, Inc. This eEdition of Enneagram Studies is a revised and expanded edition of The Enneagram, a print edition first published by Coombe Springs Press, England, in 1974.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER

APPENDIX

LIST OF FIGURES

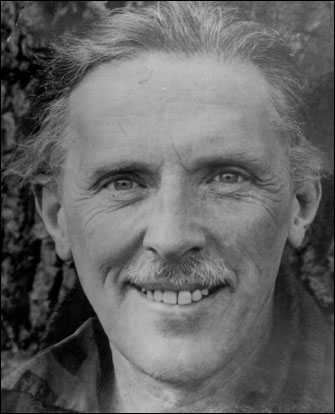

John Godolphin Bennett, 1965

We human beings belong to the world of life, but

we are not satisfied with this short and precarious

existence. We want to endure. Some want immortality

or an endless life beyond the grave. Others want to

perpetuate themselves through their children and

descendants. Many wish to live for posterity in memory

or in the works they have created. Some simply want to

put off the moment of death.

JG Bennett

unless otherwise noted, facing page quotes are from JG Bennett

Bennett taught us to take the enneagram as a study of practical enterprise, relevant to any concrete process of transformation. As such, it embraces the arts and the sciences, technology and management, religion and history.

Anthony Blake

Foreword

This book is a collection of talks and selections from journals and books by J. G. Bennett and articles by some of his students, explaining the meaning and application of the enneagram. The enneagram symbol was first shown by Gurdjieff to his groups in Russia sometime in 1916. As was typical of his methods, he claimed he was showing it in an incomplete form as a challenge to his pupils to work out its implications for themselves. Ouspensky, one of Gurdjieffs foremost students, faithfully recorded what Gurdjieff said about it. Bennett took it on board as a practical tool of understanding transformation of any kind, a universal structure. Students of Bennett rapidly became familiar with it and applied it in many areas such as educational research until it became almost second nature.

Enneagram Studies began as a smaller book entitled The Enneagram, published in 1974. At the time, J. G. Bennett was experimenting with a radically new approach to transmitting the basic know-how of the Gurdjieff methods at Sherborne House in Gloucestershire. In his original Foreword he wrote:

This book is based upon talks at Sherborne House in 1973 and 1974, given to students already familiar with Gurdjieffs ideas and revised to make them suitable for any reader interested in understanding the esoteric tradition.

The ideas in the section about the Planetary Enneagram have much in common with New Age thinking, but they have a special message for those groups who are seeking to prepare themselves for the coming times of troubles. However differently these groups may view the situation and however conflicting their detailed allegiances may appear to be, they need to know one another and share as far as possible their experience and understanding. There is no exclusive way to the truth, not even one best way, though each of us may think so. The Work, like Nature, produces a vast multitude of seeds and scatters them abroad to ensure that however many may fall by the wayside the harvest at the time of reaping will come. We must nurture our own seeds, but not, for that, neglect those of others.

Bennett died in 1974, soon after writing this Foreword. In 1978 I made a new edition of the book, this time incorporating, besides the talks, some exerts from his magnum opus The Dramatic Universe. I also included two relevant articles from the journal Bennett launched in 1964, called Systematics. In one of these, Bennett had written up material from Clarence King, who had worked in Vauxhall Motors, on the manufacturing process as seen through the eyes of the enneagram. In another, one of Bennetts students, Ken Pledge had written on what he called structured process in scientific experiment, producing what is surely the most precise and detailed example ever worked out of how the enneagram can help us understand intelligent and practical design. The additions I felt, broadened and deepened the explanations, to range over a wider field of applications, because much of what Bennett taught using the enneagram was not otherwise recorded.

The new edition was called Enneagram Studies to emphasize its wider scope. It was certainly a stimulus in the writing of my own book The Intelligent Enneagram in 1996. and have also re-organized the various chapters. The content now ranges across symbology, cooking, hazard, human transformation, manufacturing, art, the biosphere and evolution, spirituality and experimental science. It is important that contributions from some of Bennetts students have been included, because this reflects the frequent dialogues we had in groups using the enneagram as a basic tool of understanding. The variety is there so that most readers can find something they can relate to their experience, but it is useful to remember that most of them are about taking a raw material and cooking it to make a meal and any process of transformation can illuminate any other.

Many have speculated about the origins of the enneagram. It has been ascribed to as many sources as people could think of: astronomical, Sufi, alchemical, and so forth. None of these speculations have offered any substantive scholarship to support them. Confusion has reigned because it is not generally appreciated to what large extent earlier or ancient thought employed numbers and forms to structure knowledge. This was widely prevalent up to and including the Renaissance. In western culture it has its earliest known antecedent in Pythagoras, for whom number was the primary organizing principle, and whose ideas were transformed in the metaphysics of Plato and have played a considerable role in western thinking since.

Bennett himself followed Pythagoras in considering number as primary for our understanding of cosmos (on any scale). He developed a method of thinking he called systematics in which every integral number was taken as a master idea, capable of revealing cosmos in its own unique way, each leading in a progression onto the next of higher number. In doing this, he was rationalizing ancient practice while relating it to modern systems thinking. He defined a system as a set of independent but mutually relevant terms and proposed that such systems gave a way of thinking that complemented our more usual linear ways, as used in writing and calculation. It is now a common theme that our western culture is dominated by linear thinking and needs some correction; hence the call for holistic thinking. Bennetts contribution was exceptional in offering a kind of logic for this.