Professor Mary Beard - Civilisations: How Do We Look / The Eye of Faith

Here you can read online Professor Mary Beard - Civilisations: How Do We Look / The Eye of Faith full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2018, genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Civilisations: How Do We Look / The Eye of Faith

- Author:

- Genre:

- Year:2018

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Civilisations: How Do We Look / The Eye of Faith: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Civilisations: How Do We Look / The Eye of Faith" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Civilisations: How Do We Look / The Eye of Faith — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Civilisations: How Do We Look / The Eye of Faith" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

HOW DO WE LOOK?

THE EYE OF FAITH

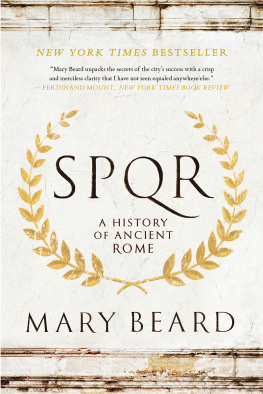

Mary Beard is a professor of classics at Newnham College, Cambridge, and the classics editor of the TLS. She has world-wide academic acclaim. Her previous books include the bestselling, Wolfson Prize-winning Pompeii, The Parthenon, Confronting the Classics and most recently, SPQR (which has sold over 140,000 copies and been translated into twenty-two languages).

ALSO BY MARY BEARD

Women & Power: A Manifesto

SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome

Laughter in Ancient Rome

The Roman Triumph

Confronting the Classics

Pompeii: The Life of a Roman Town

Its a Dons Life

All in a Dons Day

The Parthenon

The Colosseum (with Keith Hopkins)

CIVILISATIONS

HOW DO WE LOOK?

MARY BEARD

THE EYE OF FAITH

First published in Great Britain in 2018 by

Profile Books Ltd

3 Holford Yard, Bevin Way

London wc1x 9hd

www.profilebooks.com

Published in conjunction with the BBCs Civilisations series Civilisations Programme is the copyright of the BBC

Copyright Mary Beard Publications, 2018

Designed by James Alexander at Jade Design

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78125 9993

eISBN 978 178283 4205

To Matt Hill and the team

Civilisation has always been contested, argued over and impossible to pin down. In 1969 Kenneth Clark opened his BBC series Civilisation by reflecting on the concept itself: What is civilisation? he asked. I dont know. I cant define it in abstract terms yet. But I think I can recognise it when I see it. This betrayed a certain lofty self-confidence in his own cultural judgement; but Clark was also acknowledging the ragged and shifting edges of the category.

This book is written in the conviction that what we see is as important to our understanding of civilisation as what we read or hear. It celebrates a dazzling array of human creativity over thousands of years and across thousands of miles, from ancient Greece to ancient China, from sculpted human heads in prehistoric Mexico to a twenty-first century mosque on the outskirts of Istanbul. But it also prods at some of our certainties about how art works and how it should be explained. For it is not only about the men and women who with their paints and pencils, their clays and chisels created the images that fill our world, from cheap trinkets to priceless masterpieces. It is even more about the generations of humankind who have used, interpreted, argued over and given meaning to those images. One of the most influential art historians of the twentieth century, E. H. Gombrich, once wrote, There really is no such thing as art. There are only artists. I am putting the viewers of art back into the frame. Mine is not a Great Man view of art history, with all its usual heroes and geniuses.

I concentrate on two of the most intriguing and contested themes in human artistic culture. Part One highlights the art of the body, focusing on some very early depictions of men and women around the world, asking what they were for and how they were seen whether the colossal images of a pharaoh from ancient Egypt or the terracotta warriors buried with the first emperor of China. Part Two turns to images of God and gods. It takes a wider time range, reflecting on how all religions, ancient and modern, have faced irreconcilable problems in trying to picture the divine. It is not just some particular religions, such as Judaism or Islam, that have worried about such visual images. All religions throughout history have been concerned about and have sometimes fought over what it means to represent God, and they have found elegant, intriguing and awkward ways to confront that dilemma. The violent destruction of images is one end of an artistic spectrum that has idolatry at the other.

Part of my project is to expose the very long history of how we look. All over the world ancient art, its debates and its controversies still matter. In the West, the art of classical Greece and Rome in particular and the different engagement people have had with that tradition, over many centuries still has an enormous impact on modern viewers, even if we do not always recognise it. Western assumptions about what a naturalistic representation of the human body is date back to a particular artistic revolution in Greece around the turn of the sixth and fifth centuries BCE. And many of our ways of talking about art continue the conversations of the classical world. The modern idea that the female nude implies the existence of a predatory male gaze was not first thought up, as is often imagined, in the feminism of the 1960s. As Part One will explain, what is believed to be the very first life-sized statue of a female nude in classical Greece a fourth-century BCE image of the goddess Aphrodite provoked exactly the same kind of debate. And some of the earliest intellectuals that are known to us argued fiercely about the rights and wrongs of portraying gods in human form. One sixth-century BCE Greek philosopher sharply observed that if horses and cattle could paint and sculpt, they would represent the gods just like themselves as horses and cattle.

Clarks opening question What is civilisation? is one of my own main questions too. The two parts of this book are based on two programmes I wrote for the new BBC series of Civilisations, first broadcast in 2018. This was an attempt not to re-make Clarks original version, but to take a fresh look at its themes with a much wider frame of reference, moving outside Europe (Clark once or twice strayed across the Atlantic, but that was all), and back into prehistory. That is what the plural in the new title indicates.

I am even more concerned than Clark with the discontents and debates around the idea of civilisation, and with how that rather fragile concept is justified and defended. One of its most powerful weapons has always been barbarity: we know that we are civilised by contrasting ourselves with those we deem to be uncivilised, with those who do not or cannot be trusted to share our values. Civilisation is a process of exclusion as well as inclusion. The boundary between us and them may be an internal one (for much of world history the idea of a civilised woman has been a contradiction in terms), or an external one, as the word barbarian suggests; it was originally a derogatory and ethnocentric ancient Greek term for foreigners you could not understand, because they spoke in an incomprehensible babble: bar-bar-bar The inconvenient truth, of course, is that so-called barbarians may be no more than those with a different view from ourselves of what it is to be civilised, and of what matters in human culture. In the end, one persons barbarity is another persons civilisation.

Wherever possible I try to see things from the other side of the dividing line, and to read civilisation against the grain. I shall be looking at some images from the distant past with the same suspicious eyes that we usually keep for those in the modern world. It is important to remember that plenty of ancient Egyptian viewers, or ancient Romans, may have been just as cynical about the colossal statues of their rulers as we now are about the parade of images of modern autocrats. And I shall be looking at some of those on the losing, as well as the winning, sides in the historic conflicts over images, and over what should and should not be represented, or how. Those who destroy statues and paintings whether in the name of religion or not are regularly seen in the West as some of historys worst barbarian thugs, and we lament the works of art that, thanks to these iconoclasts, we have lost. But, as we shall see, they have their own story to tell too, even their own artfulness.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Civilisations: How Do We Look / The Eye of Faith»

Look at similar books to Civilisations: How Do We Look / The Eye of Faith. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Civilisations: How Do We Look / The Eye of Faith and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.