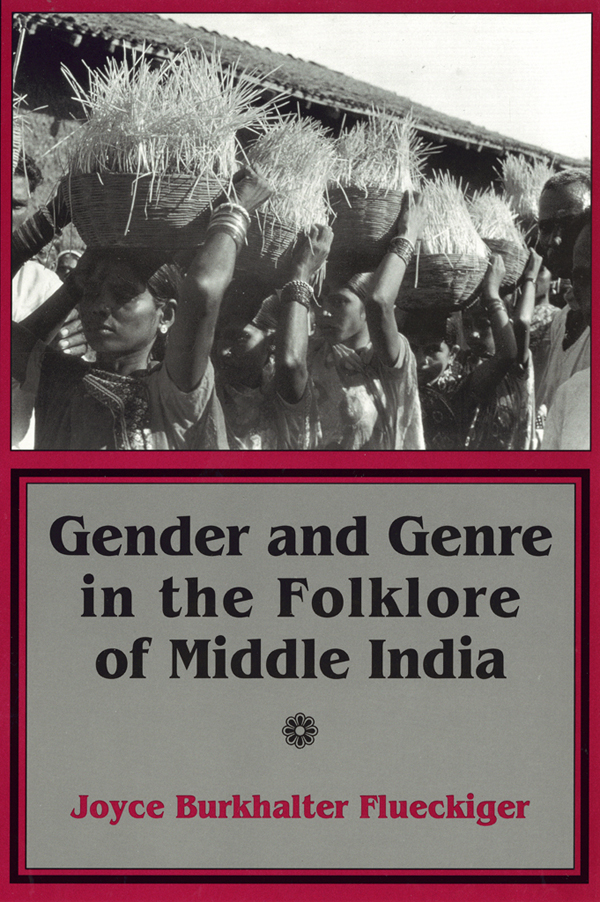

with thanks to

my parents, Edward and Ramoth Burkhalter,

and the performers and audiences of Chhattisgarh

Illustrations and Maps

ILLUSTRATIONS

MAPS

Foreword

G REGORY N AGY

Gender and Genre in the Folklore of Middle India, by Joyce Burkhalter Flueckiger, demonstrates the necessity of defining any given genre as a part of a system of genres as they exist at a given time and place within a given community. Thus we cannot speak of, say, epic as a genre of and by itself until we establish how the form that we call epic fits into a system of other forms that are complementary to it. Moreover, we cannot expect a genre such as epic to be a constantlet alone a universalsince different communities are marked by different systems of complementarity. Even a single community may have had different systems at different phases of its existence, so that the nature of a genre like epic may change over time.

Together with another book in the Myth and Poetics series, Dwight Reynoldss Heroic Poets, Poetic Heroes: The Ethnography of Performance in an Arabic Oral Epic Tradition, Flueckigers work will force a radical revision of the concept of epic. In Reynoldss book, epic is seen as crossing class boundaries. In Flueckigers we see epic crossing gender boundaries as well. Such shifts, Flueckiger argues, can be understood only within an overall system of genres.

From earlier studies of the occasions of public performance in the living epic traditions of India there arose the scholarly consensus that epic is performed almost exclusively by male singers. The rarely found exceptions, however, are particularly revealing, and Flueckiger has been a pioneer of research in such crossovers of gender and genre. Moreover, her discoveries of exceptional epic crossovers in the repertoires of women performers provide a major impetus for comparative study. We can now see in a new light, for example, the song of Sappho about the wedding of Hektor and Andromache, considered exceptional in the history of Greek literature: that song, composed in a meter cognate with but distinct from the epic dactylic hexameter, treats in a nonepic manner themes that are otherwise characteristic of epic.

Flueckigers book, the result of fieldwork conducted over a period of fifteen years on the oral traditions of the Chhattisgarh region of Middle India, describes in detail six genres that typify this community. These genres define themselves through their interrelationships in performance traditions and, implicitly, in the repertoires of individual performers. By closely studying these interrelationships, the author has succeeded in capturing the essence of what is known as a song culture, that is, a kind of social setting in which the performances of songs are not distinguished from the performances of rituals that happen to be basic to that setting. To the extent that a community identifies itself by way of its ritualsand by way of the myths to which they are connecteda song culture is the sum of its myths and rituals. The six genres studied in this book illuminate a new way to look at poetics, that is, through the lens of an indigenous song culture.

Preface

This book examines the indigenous principles of genre identification and intertextuality within a folklore repertoire of middle India and proceeds to use these principles as an entry into the interpretation of six performance genres selected from that repertoire. This focus for the study of the folklore of the Chhattisgarh region of Madhya Pradesh took shape only gradually over the course of fifteen months of original fieldwork and numerous return trips to Chhattisgarh over the last fifteen years.

I first went to Chhattisgarh in the fall of 1980 on a Fulbright-Hays Dissertation Research Grant with a plan to look for regional variants, particularly womens performance traditions, of the pan-Indian epic tradition of the Ramayana. My motivating question was whether and how the performance of a particular Ramayana tradition might define a cultural region and/or social groups within that region. Given the ritual dominance of the Hindi written version of the Ramayana, the Rmcaritmnas, in the Hindi-speaking belt of northern and middle India, I expected that specifically regional and gender- or caste-based variants and interpretations of the epic story would be embedded in nonepic forms, such as folk songs and tales or devotional songs. So, I began my fieldwork by taping a wide spectrum of ritual and festival performances that occurred in the villages in which I lived and visited. After several months in the field, I came to a realization that while many Chhattisgarhi folk traditions offered alternative narrative variants, emphases, and worldviews to that of the Hindi Rmcaritmnas, genres in which these were embedded were both more interesting to me and more significant to those who performed them than was the Ramayana tradition per se.

I shifted my focus to a consideration of this folklore repertoire as a system of genres, listening to performers and audiences articulations of the boundaries of what they perceived to be a Chhattisgarhi repertoire and making an effort to identify its internal organizing principles and categories. I found the question I had brought to my original research topic of regional Ramayanas still relevant, although now significantly expanded: could a region or social groups within that region be identified by the performance of particular genres, and if so, how; what were the relationships between genre and community? In the course of my fieldwork, it gradually became apparent that a central organizing feature of the repertoire of Chhattisgarhi folk genres is the social identity of the group to whom the genre belongs; performers and audiences categorize genres on the basis of this social identity more frequently than on the basis of form or thematic content. Performance of these genres both identifies and contributes to the identity of the Chhat-tisgarh folklore region and social groups within it.

Western scholars have conducted few ethnographic studies in Chhat-tisgarh, This was perhaps the primary motivation for my return to Chhat-tisgarh as a field sitemy desire to understand within an analytic framework this region of middle India which I had come to know on some intuitive level as a child and which remains an important part of who I have become.

I began my fieldwork by living for several months in the village of Pathar-la, on the eastern borderlands of Chhattisgarh, ten kilometers from the village where my parents, Ramoth and Edward Burkhalter, were Mennonite missionaries and where I had numerous friends and contacts from my childhood. Here, I gradually internalized the rhythms of village life I had previously known only from a distance and observed the ways in which performance both creates and reflects those rhythms. I became aware of a wide spectrum of Chhattisgarhi performance genres, their rules of usage, and Chhattisgarhi ways of talking about performance and eventually decided to make this regional repertoire the focus of my study.

The village in which I first lived was primarily an Oriya-speaking village in the subregion of Phuljhar, with several Chhattisgarhi-speaking villages close by. Even within the latter, however, many genres identified as Chhattisgarhi were not uniformly available (such as the candain epic tradition). To make a study of a regional repertoire would require a wider geographic field. So after several months I moved to the more centrally located town of Dhamtari in the plains of Chhattisgarh, from where I could more easily locate and access Chhattisgarhi performance genres not available in the regions borderlands.

Next page