Table of Contents

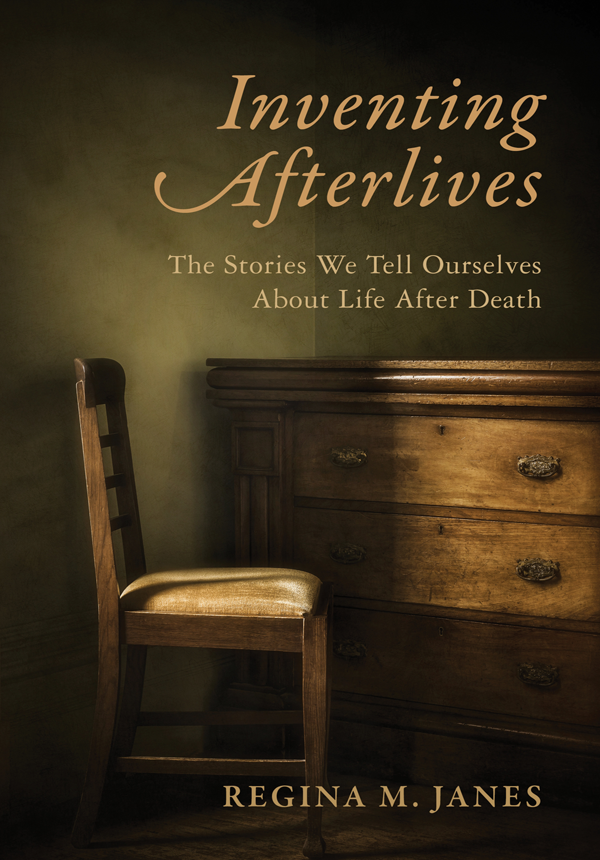

INVENTING AFTERLIVES

INVENTING AFTERLIVES

THE STORIES WE TELL OURSELVES ABOUT LIFE AFTER DEATH

REGINA M. JANES

Columbia University Press

New York

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2018 Columbia University Press

Gabriel from Gabriel: A Poem by Edward Hirsch, copyright 2014 by Edward Hirsch. Used by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

I Am a Cat, by Natsume Sseki, copyright 2002 by Aiko Ito and Graeme Wilson. Used by permission of Tuttle Publishing, a division of Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd.

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-54629-4

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Janes, Regina M., author.

Title: Inventing afterlives : the stories we tell ourselves about life after death / Regina M. Janes.

Description: 1 [edition]. | New York : Columbia University Press, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018000804 (print) | LCCN 2018009938 (e-book) | ISBN 9780231546294 (e-book) | ISBN 9780231185707 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780231185714 (paperback)

Subjects: LCSH: Future life.

Classification: LCC BL535 (e-book) | LCC BL535 .J35 2018 (print) | DDC 202/.3dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018000804

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Cover design: Lisa Hamm

Cover image: Amy Weiss/Trevillion Images

IN MEMORIAM DALE E. WOOLLEY

AND FOR CHARLES, THE ONLY AFTERLIFE DALE EVER TOOK AN INTEREST IN

CONTENTS

LEO (July 23Aug. 22)

The FBI will have to ask you some tough questions next week, such as whether true love really exists and what happens after we die.

HOROSCOPE, THE ONION, OCTOBER 1319, 2011, 9.

D avid Hume had an answer for the FBI. The single most famous event in that British philosophers life was a visit James Boswell, Samuel Johnsons biographer-to-be, paid him in 1776. Nothing endears so much a friend as sorrow for his death, Hume had observed, yet it was not sorrow moving Boswell to Humes side, but curiosity. As Hume lay dying, Boswell came to see how an atheist died. Serenely and cheerfully, was the answer, with no itchy desire after eternal life, no fear of roasting in flames, no apprehensions about annihilation, and no dread of the gaping gap of vanished consciousness. Boswell had bad dreams for a week.

To begin a book about afterlives with someone who did not believe in one may seem perverse, but it has a purpose. Everyone has some belief, or beliefs, about what happens after death, even if the belief is that nothing at all happens or that nothing can be known about what happens or that there is no point even thinking about it. Once death becomes a phenomenon that human beings can think and talk about, we inevitably ask, So what comes next; whats after that? The question applies both to the dead and to the survivors, and answers range from nothing to eternities. Whatever the answer, it establishes our relationship to the cosmos we live in: what it means, what it is for, and how we are to live within it while we live.

Death, of course, has at once everything and nothing to do with the afterlife. Afterlives are narratives made by the living in order to define the relationship between the living and the dead, between the self and the prospect of its own death, between survivors and those who have disappeared from the social unit. Death is the limit that provokes those fictions. Out of deaths blank wall, we want to make a gate, and then we demand to know what is on the other side of the gate. Hume vanished without fear. Boswell lived less happily, complaining of his melancholy the year before Hume died, [A]ll the doubts which have ever disturbed thinking men, come upon me. I awake in the night, dreading annihilation or being thrown into some horrible state of being. Many presume on paradise.

The word afterlife presupposes some posthumous existence, pleasant or unpleasant, but beliefs about what happens after life include the denial of any such existence. Whether an afterlife is affirmed or denied, the afterlife narrative overcomes death, dominates it, and reintegrates death and the dead into the continuing self-conceptions of the living. When blurb writers exclaim, This book is not about death, its really about how to live! they are describing not a happy accident but a necessary fact.

As the word changes, so does the concept, less state and more life.

In religious studies, afterlives accompany the complex and nuanced understanding of a religious tradition over time and in time. Scholars maintain a careful professional agnosticism as to the reality of intrinsically unverifiable afterlives and the claims of contending traditions. What a tradition maintains as to immortality is accepted as given, while its chops and changes, responses to political and intellectual ferment, differences from itself from moment to moment, form the object of study. Creating new knowledge through meticulous detail, religious-studies scholars are rightly suspicious of grand historical narratives and ahistorical cognitive arguments. This study proceeds otherwise.

It proposes a fable of origins in cognitive studies because the irreligious, too, need to be accounted for. As unbelievers like Hume demonstrate, there is no hard wiring of afterlife belief (or God), but afterlife beliefs (like God) do originate in human sociality and cognition, that is, language. Other primates recognize death and dislike it, but they have nothing to say about it. Human afterlife talk weaves death into lifes narrative, if only to write FINIS, as Walter Benjamin implies. Religious traditions occasionally recount the origins of their afterlife beliefs, while those outside those traditions (and outside of religious studies) commonly explain away those beliefs in functional terms ranging from condescending to paranoid: as compensatory or consoling or ethical or controlling or imitative or stolen.

Yet the earliest attested afterlife beliefs (and some still current) are not compensatory, consoling, ethical, or controlling. Nor can we know what they may imitate or from whom they may have been stolen. They neither satisfy human desires nor have anything to do with justice or morality. Some other explanation is necessary, for people wanting explanations. The human mind seems the place to look. But not just the mind: human minds are always (already) social. Proposed is an ahistorical account that accommodates both the cognitive quandary death poses and the social injury it creates.

This ahistorical deep structure (a modern mythos) supports, but does not determine, the variety afterlives display in changing socio-political and economic circumstances. That morality and the afterlife originate independently is not immediately obvious. The misery of some early afterlives we have never known, and we have forgotten the horrors of earlier iterations of our own. Only very latelyand still not universallydo justice and morality attach themselves to afterlife beliefs, and only in the enlightenment does human happiness come to dominate afterlife expectations. These claims require demonstration that only a narrative traversing many places and times can supply, if they are to persuade.