Copyright 2016 by Pierre Conesa

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

First North American Edition 2018.

First Published 2016 in France by Robert Laffont.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

Cover design by Rain Saukas

ISBN: 978-1-5107-3663-4

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-5107-3664-1

Printed in the United States of America

CONTENTS

I think that one of the tragedies of this story is that the Saudi Arabians exported their problem by financing schoolsthe madrassasall through the Islamic world. The Saudi Arabian government had two wings. The mainland Saudi leadership went into financial issues and defense issues, and controlled the elite establishment in order to purchase support. From the more fundamentalist religious groups, they gave certain other ministries, the religious ministries, education ministries, to more fundamentalist Islam leaders. And thats how the split occurred.

So the Saudi government was, to a certain extent, pursuing internally inconsistent policies throughout this periodreaching out to the West with sophisticated, well educated, internationally minded leaders like its foreign minister, like its ambassador in Washington and others. At the same time, it was funding with this vast oil revenue a different set of efforts: education, which was narrowly based on the Koran

R ICHARD H OLBROOKE ,

former US Ambassador to the UN,

who did not mince his words, during an

interview granted in 2014.

FOREWORD

by Hubert Vdrine

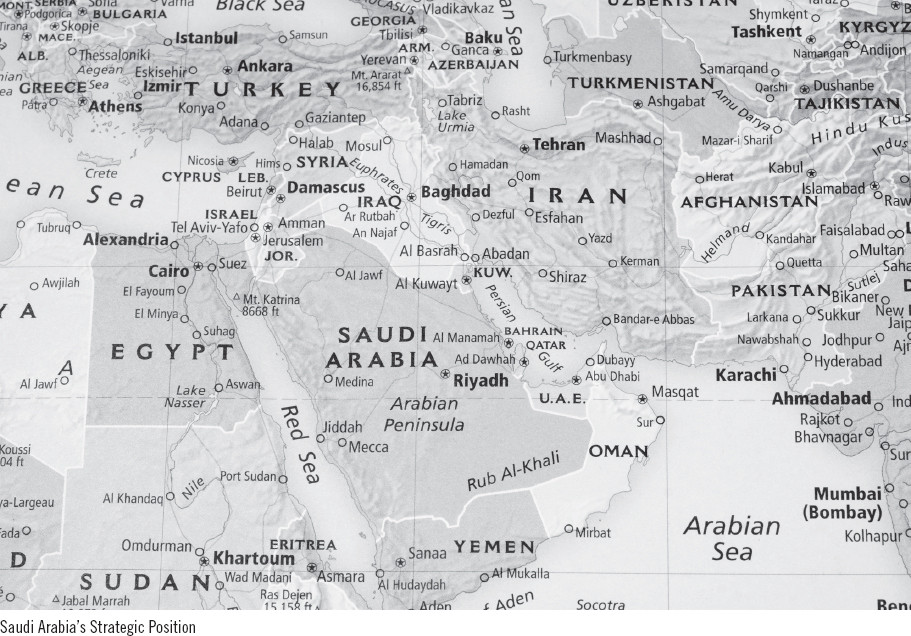

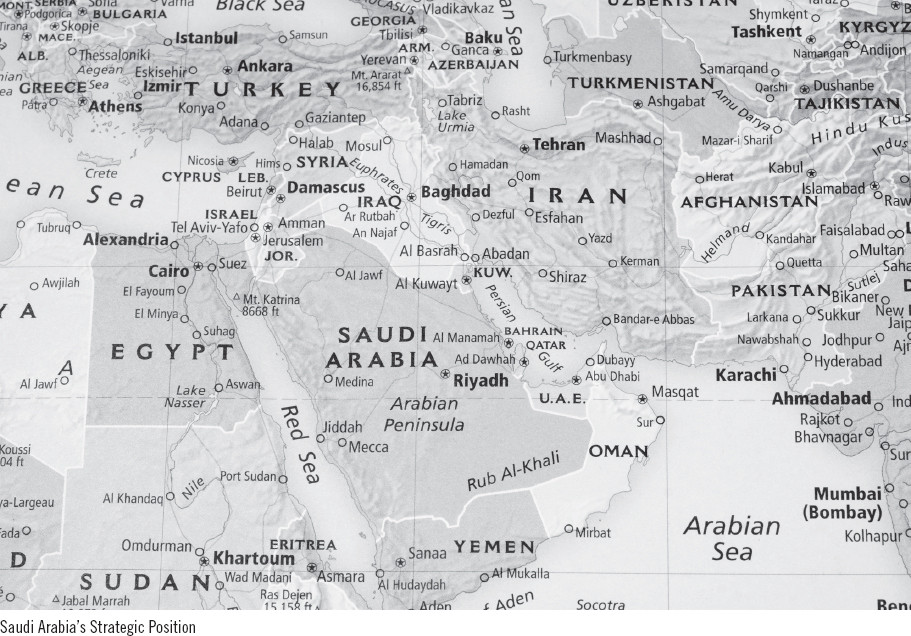

Considering the major position Saudi Arabia has enjoyed in the oil economy and global geopolitics since the famous encounter between King Abdulaziz and President Roosevelt on the American cruiser, Le Quincy , on his return from Yalta, over seventy years ago, Pierre Conesas book is essential in order to better decipher this country, as well as the Saudi regime, its vision of the world, and its policies.

Seven sovereigns down the line, under the reign of King Salman, who succeeded King Abdullah on January 23, 2015, the need to understand is even more acute because new questions are being raisedquestions that had not been explicitly formulated earlier, in particular with regard to Saudi Arabias role in recent decades in the propagation of a fundamentalist sect of Islam known as Wahhabism. At the same time, Saudi Arabia is facing the internal consequences of its oil policy, as well as Irans inevitable return to the international arena. It is important to try to understand, beyond any immediate reactions, how Saudi Arabia will react to all this in the long term.

In particular, it is Saudi Arabias religious diplomacy that Pierre Conesa has undertaken to analyze in this book. It is posited that this kind of proselytism is embedded in the Saudi regimes DNA and encompasses both the teaching and propagation of the faith, Conesa does not hide the fact that his approach is very critical. In fact, he analyzes Wahhabism, and Salafismwhich, according to the author, go hand in handas a totalitarian political ideology deployed against Arab nationalism, Shiism, Iran, and the Western ideology of democracy and human rights.

He analyzes the history of this religious diplomacy, always critically, before and after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and its various areas of action: countries in the first circle, countries with a Muslim minority, the former Yugoslavia, the former USSR, European countries, North America and Australia. The upheavals and convulsions of the last twenty years and the rising power of Salafism in many parts of the world have led him to describe Saudi Arabia as a Dr. Jekyll, surpassed by its alter-ego, Mr. Hyde.

Pierre Conesa has, of course, studied the internal workings of Saudi-Wahhabism, but it is its outer dimension of a soft worldwide ideological power that interests him the most. In this respect, how can we dispute the legitimacy of such an approach, since it is true that the world today would be incomprehensible without taking into account the conventional power relations between states, global enterprises and financial powerhouses, but also soft power in all its forms? To begin with there is, of course, the global soft power of the United States (indeed, the American professor, Joseph Nye, used this concept to recommend a more sophisticated use of American power).

Nor can we fail to think of the soft power of Israel as well; the one the European Union hoped to exert, precisely because of its rejection of the balance of power, before it started doubting itself; the one that France reckons it has held on to through multiple levers, including Francophony; the one that Putins Russia wishes to develop by allying itself with the Orthodox Church (moreover, when Putin goes to Mount Athos, we speak of religious diplomacy); the Vaticans soft powerwhich is obvious; that of the Dalai Lama; of NGOs as well as diasporas (Chinese, Iranian, African, etc.) and the countless lobbies So there is nothing unusual about analyzing Saudi Arabia from this point of view, not just from the perspective of the oil industry.

In so doing, Pierre Conesa fills a gap in the political analysis of a mode of action that has profoundly changed international relations, since to our knowledge there is no book in English or French on this subject.

It is especially useful for France, which has becomeamong other things, due to its long-standing, strict secularismthe country least able to understand the deep-seated persistence of religious phenomena and has long been content with superficial generalities about Islam, Sunnis and Shiites, the dialogue of cultures, and so on.

This rigorous but well-argued work, which will evidently arouse strong reactions, makes us want to go even further with the analysissomething the author himself calls for.

Further work is needed on the sources and drivers of todays Islamism and its extreme forms. Should such a study be limited only to Saudi Arabia and Wahhabi sources? Shouldnt it be extended to other countries, some of the Emirates, for example? To Muslim religious institutions, not necessarily linked to Saudi Arabia?

But also, more broadly speaking, what should one think of the way Erdogans Turkey has evolved from this point of view? How far can the re-Islamization of the country go? Why have other Muslim countriesin the Middle East, the Maghreb, Africa, and so on, which are often proponents of a very different, less extremist Islamallowed themselves to be so strongly influenced? Is it a question of resources? Ideology? Resignation on the part of political authorities?