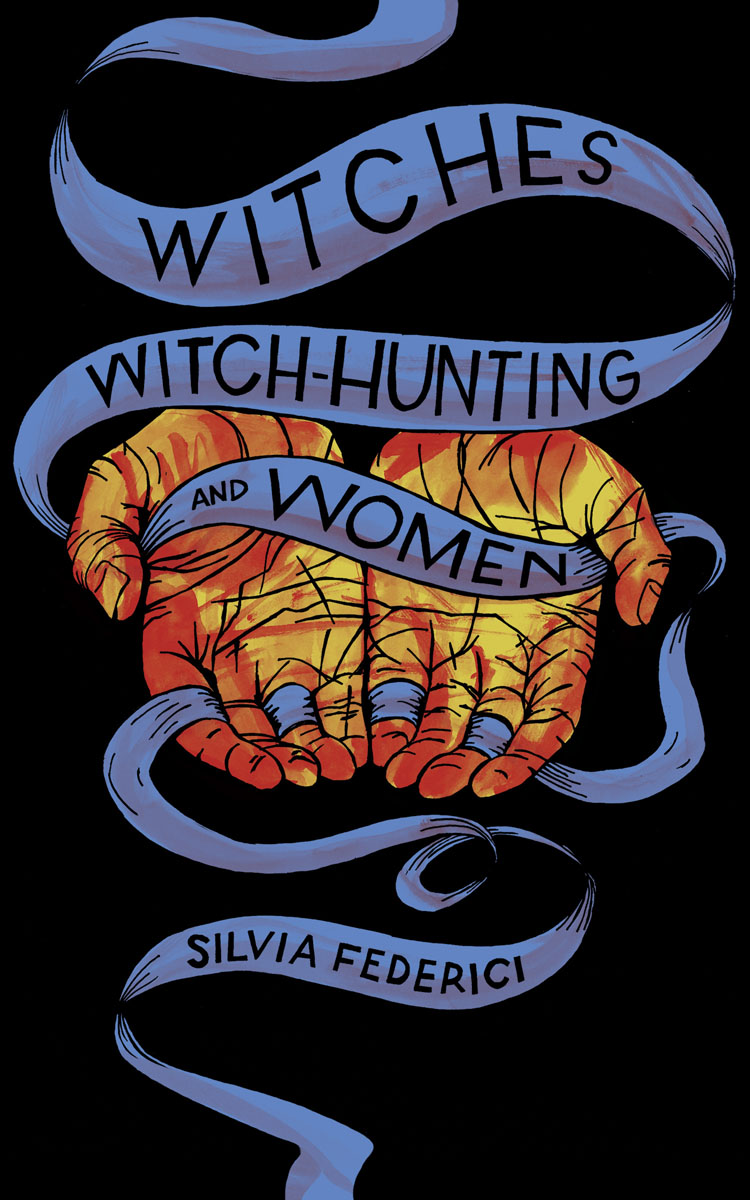

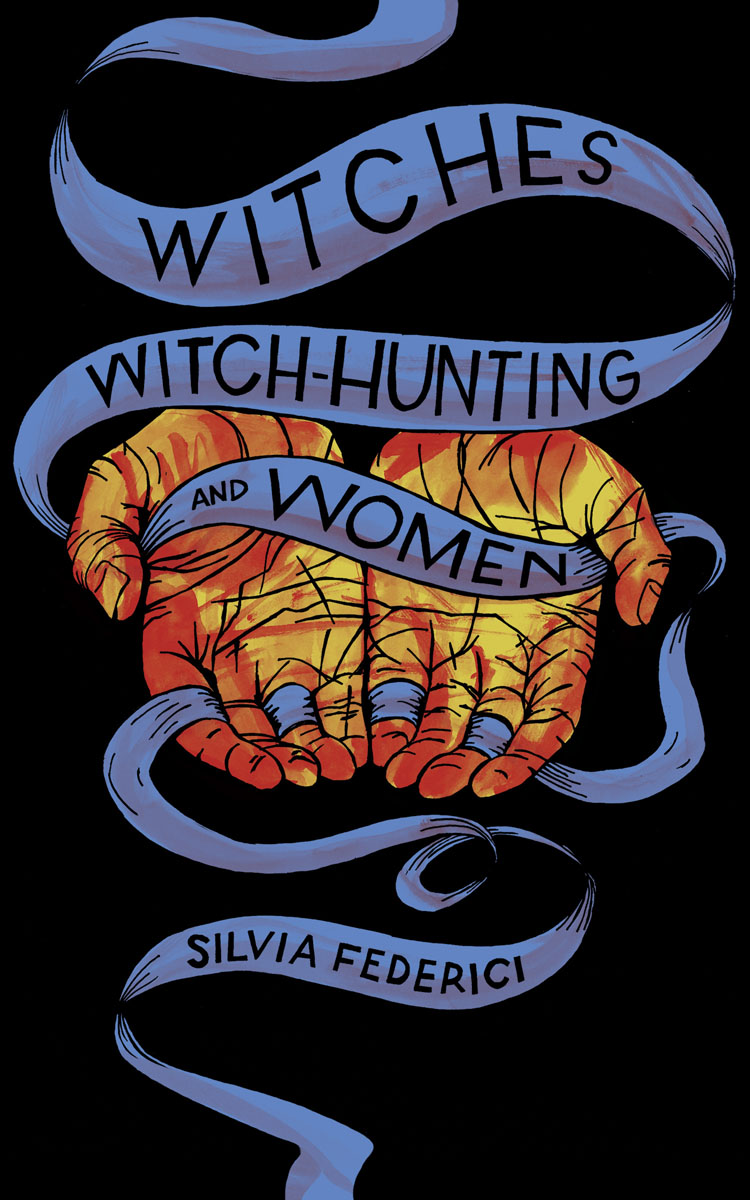

Witches, Witch-Hunting, and Women

Silvia Federici

PM Press 2018

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be transmitted by any means without permission in writing from the publisher.

ISBN: 9781629635682

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018931519

Cover by Josh MacPhee

Interior design by briandesign

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

PM Press

PO Box 23912

Oakland, CA 94623

www.pmpress.org

Autonomedia

PO Box 568 Williamsburg Station

Brooklyn, NY 11211-0568 USA

www.autonomedia.org

Common Notions

314 7th Street Brooklyn, NY 11215

www.commonnotions.org

This edition first published in Canada in 2018 by Between the Lines

401 Richmond Street West, Studio 281, Toronto, Ontario, M5V 3A8, Canada

18007187201

www.btlbooks.com

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be photocopied, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher or (for photocopying in Canada only) Access Copyright www.accesscopyright.ca.

Canadian cataloguing information is available from Library and Archives Canada.

ISBN 9781771133746 Between the Lines paperback

ISBN 9781771133753 Between the Lines epub

ISBN 9781771133760 Between the Lines pdf

Printed in the USA by the Employee Owners of Thomson-Shore in Dexter, Michigan. www.thomsonshore.com

Contents

PART ONE

Revisiting Capital Accumulation and the European Witch Hunt |

PART TWO

New Forms of Capital Accumulation and Witch-Hunting in Our Time |

Acknowledgments

T his book owes its existence to the work, encouragement, and advice I received from Camille Barbagallo, who has read the material included through its several revisions and helped me with her suggestions and insights to conceive of it as one continuous discourse. I also owe special thanks to Rachel Anderson and Cis OBoyle, caretakers of Idle Women, an artist-led organization, who asked me to write the history of the change in the meaning of gossip, and to Kirsten Dufour Andersen, who with other women whose names I cannot recall, at her art center in Copenhagen, gave me the text and the translation of Midsommervisen. Special thanks also to Josh MacPhee for designing the cover of the book, and to the books copublishers, Ramsey Kanaan of PM Press, Jim Fleming of Autonomedia, and Malav Kanuga of Common Notions. Thanks, not last, to the many young women who in recent years have received my presentation of Caliban and the Witch with great enthusiasm and have immediately seen the relation between the witch hunts of the period of primitive accumulation and the new surge of violence against women. To all of themwho proudly say, We are the granddaughters of all the witches you could not burn, somos las nietas de todas las brujas que no pudiste quemar, as the popular chant goesthis book is dedicated.

Introduction

V arious factors have convinced me to publish the essays contained in this volume, even though they only trace the beginning of a new investigation and to some extent, at least in , propose theories and provide documentation already covered in Caliban and the Witch. One factor is the request often addressed to me recently to produce a popular booklet revisiting the main themes of Caliban and the Witch that could reach a broader audience. To this I must add my desire to continue to research some aspects of the witch hunts in Europe that are of particular relevance for understanding the economic/political context that generated them. I have focused on two in this volume, although I expect to continue this work with further research on the relation between women and money as constituted by the ideological campaign that accompanied the witch hunt, on the role of children as accusers and accused in the trials, and above all on witch-hunting in the colonial world.

In this book, I reconsider the social environment and motivations that produced many of the witchcraft accusations. In particular, I focus on two themes. First, the relation between witch-hunting and the contemporary process of land enclosure and privatization. This saw the formation of a class of land proprietors turning agricultural production into a commercial venture and, at the same time, with the fencing of the communal lands, the formation of a population of beggars and vagabonds that posed a threat to the developing capitalist order. These changes were not purely of an economic nature but invested every aspect of life, producing a major realignment of social priorities, norms, and values. Second, I discuss the relation between witch-hunting and the increasing enclosure of the female body through the extension of state control over womens sexuality and reproductive capacity. The fact that these two aspects of the European witch hunts are treated separately does not imply, however, that they were separate in actual life, for poverty and sexual transgression were common elements in the lives of many women condemned as witches.

As in Caliban and the Witch, I reiterate that women were the main target of this persecution, because it was they who were most severely impoverished by the capitalization of economic life, and because the regulation of womens sexuality and reproductive capacity was a condition for the construction of more stringent forms of social control. The three articles that I have included, however, question the view that women were only victims of this process, stressing the fear they inspired in the men at the helm of change in the countries and communities in which they lived. Accordingly, the opening articles in this collection, Witch-Hunting and the Fear of the Power of Women and Witch Hunts, Enclosures, and the Demise of Communal Property Relations, highlight the authorities fear of womens rebellion and power of fascination, while On the Meaning of Gossip traces the shift in the meaning of the word from its positive connotation of female friendship to the negative one that refers to malignant speech, alongside the parallel degradation of the social position of women spearheaded by the witch hunt.

Both of these texts are but an introduction to topics that require further inquiry and research. Other concerns, also includes an essay that I wrote in 2008 on the return of witch-hunting in many parts of the world in conjunction with developments that have paved the way to the globalization of the world economy.

More than five centuries have passed since witchcraft appeared in the legal codes of many European countries, and women reputed to be witches became the target of a mass persecution. Today most governments in countries where women are assaulted and murdered as witches do not acknowledge the crime. Nevertheless, at the roots of the new persecution we find many of the same factors that instigated the sixteenth- and seventeenth-century witch hunts, with religion and the regurgitation of the most misogynous biases against women providing the ideological justification.

Since 2008, when Witch-Hunting, Globalization, and Feminist Solidarity in Africa Today was first published, the records of the murders perpetrated in the name of witchcraft have swelled. In Tanzania alone, it is calculated that more than five thousand women a year are murdered as witches, some macheted to death, others buried or burned alive. In some countries, like the Central African Republic, the prisons are full of accused witches, and in 2016 more than a hundred were executed, burned at the stake by rebel soldiers, who, following in the footsteps of sixteenth-century witch finders, have made a business of the accusations, using the threat of a pending execution to force people to pay.

Next page