Jean Piaget: If children fail to understand one another, it is because they think they understand one another. The explainer believes from the start that the reproducer will grasp everything, will almost know beforehand all that should be known.... These habits of thought account, in the first place, for the remarkable lack of precision in childish style.

How do human minds develop? We know that our infants are already equipped at birth with ways to react to certain kinds of sounds and smells, to certain patterns of darkness and light, and to various tactile and haptic sensations. Then over the following months and years the child learns many more perceptual and motor skills, and proceeds through many stages of intellectual development. Eventually, each normal child learns to recognize, represent, and reflect upon some its own internal states, and also comes to self-reflect on some its intentions and feelingsand eventually learns to identify these with aspects of other persons that it observes. This section will speculate about possible structures we might use to support those activities; the next section will suggest some ideas about how children might develop these.

This book has proposed several different views of how a human mind might be organized. We began by portraying the mind (or brain) as based on a scheme that deals with various situations by activating certain sets of resourcesso that each such selection will function as a somewhat different way to think.

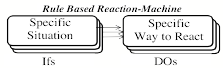

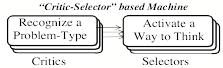

To determine which set of resources to select, such systems could begin with some simple sorts of If>Do rules. Later these develop into more versatile Critic>Selector systems.

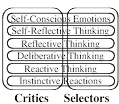

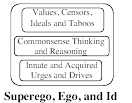

Chapter 5 conjectured that the adult mind comes to have multiple levels of organization. Each level has Critics to recognize situations and Selectors that can activate appropriate ways to think, by exploiting the resources at its own and at other levels. We also noted that these ideas could be seen as consistent with Sigmund Freuds early view of the mind as a system for resolving (or for ignoring) conflicts between our instinctive and acquired ideas.

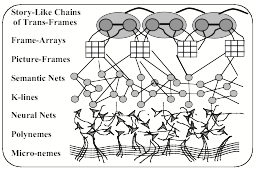

In chapter 8 we also reviewed various ways to represent knowledge and skills, and noted that these could be arranged in a stack with increasing degrees of expressiveness.

Each of those ways to envision a mind has different kinds of virtues and faults, so it would make little sense to ask which model is best. Instead, one needs to develop Critics that learn good ways to choose when and how to switch among them.

Is a Mind like a Human Community?

Perhaps a more popular model of mind portrays our mental processes as like a human communitysuch as a residential town or a company. In a typical corporate organization, the human resources are (formally) organized in accord with some hierarchical plan.

We tend to invent such management trees whenever theres more than one person can do; then the work is divided into parts, which then are assigned to subordinates. This picture suggests that one might try to identify a persons Self with the Chief Executive of that company, who controls the rest through a chain of command in which instructions tend to branch down from the top.

However, this is not a good model for human brains because an employee of a company is a person who might be able to learn to perform virtually any new taskwhereas, most parts of a brain are too specialized to do such things. This difference may be important because, when a Company becomes wealthy enough, it may be able to expand itself: when it wants to include new activities, it can hire additional employee-minds. In contrast, we humans dont (yet) have practical ways to expand our own individual brains. So, whenever you add a additional task (or break a large one into smaller parts)and then try to do them all at oncethen each sub-process will lose some of its competence, because it now has access to fewer resources. Perhaps we should state this as a general principle.

The Parallel Paradox: If you break a large job into several parts, and then try to work them all at oncethen each process may lose some competence, from lacking access to resources it needs.

There is a popular belief that the brain gets much of its power and speed because it can do things many things in parallel. Indeed, it is clear that many of sensory, motor, and other systems do many things simultaneously. However, it also seems clear that as we tackle more complex and difficult goals, we increasingly need to divide those problems into subgoalsand then focus on these sequentially. This means that our higher, reflective levels of thought will tend to operate more serially.

This is less of a problem for a company, which can often divide a problem into parts, which it then can pass down to separate subordinates, who can deal with them all simultaneously. However, that leads to a different kind of cost:

The Pinnacle Paradox: As an organization grows more complex, its chief executive will understand it less, and will need to increasingly place more trust in decisions made by subordinates. (See Parallel Paradox.)

However, many human communities are less hierarchical than the companies that we just described, and make their decisions by using more cooperation, consensus, and compromise. There is usually some leadership, but in a working democracy, those leaders are somehow given authority by the membership to help, when needed, to assist in making decisions and settling arguments. Such negotiations can be more versatile than majority rule, which gives to each participant a spurious sense of making a differencewhereas that feeling ignores the fact that almost all differences get cancelled out. This raises questions about the extent to which our human sub-personalities cooperate to help us accomplish larger jobsbut we dont know enough to say much about this.

Central and Peripheral Controls

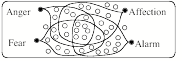

Every higher animal has evolved many resources that can interrupt its higher level processes, in reaction to certain states of affairs. These conditions include such signs of possible dangers as rapid motions and loud sounds, unexpected touches, and the sighting of insects, spiders, and snakes. We also react to such bodily signs of aches and pains, feelings of illness, and such needs as hunger and thirst. Similarly, we are subject to more pleasant kinds of interruptions, such as the sights and smells of foods to eat, and of signals of sexual interest.

Many such reactions work without interrupting most mental activitiesas when your hand scratches an insect bite, or when you move into shade to avoid excessive light. A few of these mainly instinctive alarms are:

Next page