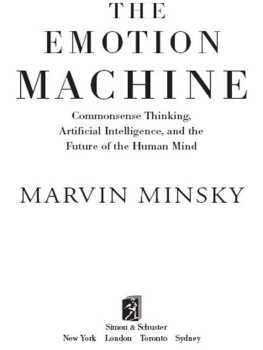

The Society of Mind

Marvin Minsky

Illustrations by luliana Lee

Copyright 1985, 1986 by Marvin Minsky

All rights reserved including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form.

Designed by Irving Perkins Associates Manufactured in the United States of America

3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2 7 9 10 8 Pbk.

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Minsky, Marvin Lee, date.

The society of mind.

1. Intellect. 2. Human information processing.

3. SciencePhilosophy. I. Title. BF431.M553 1986 153 86-20322

ISBN 0-671-60740-5 ISBN 0-671-65713-5 Pbk.

Chapter 1

PROLOGUE

Everything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler.

Albert Einstein

This book tries to explain how minds work. How can intelligence emerge from nonintelligence? To answer that, well show that you can build a mind from many little parts, each mindless by itself.

Ill call Society of Mind this scheme in which each mind is made of many smaller processes. These well call agents. Each mental agent by itself can only do some simple thing that needs no mind or thought at all. Yet when we join these agents in societiesin certain very special waysthis leads to true intelligence.

Theres nothing very technical in this book. It, too, is a societyof many small ideas. Each by itself is only common sense, yet when we join enough of them we can explain the strangest mysteries of mind.

One trouble is that these ideas have lots of cross-connections. My explanations rarely go in neat, straight lines from start to end. I wish I could have lined them up so that you could climb straight to the top, by mental stair-steps, one by one. Instead theyre tied in tangled webs.

Perhaps the fault is actually mine, for failing to find a tidy base of neatly ordered principles. But Im inclined to lay the blame upon the nature of the mind: much of its power seems to stem from just the messy ways its agents cross-connect. If so, that complication cant be helped; its only what we must expect from evolutions countless tricks.

What can we do when things are hard to describe? We start by sketching out the roughest shapes to serve as scaffolds for the rest; it doesnt matter very much if some of those forms turn out partially wrong. Next, draw details to give these skeletons more lifelike flesh. Last, in the final filling-in, discard whichever first ideas no longer fit.

Thats what we do in real life, with puzzles that seem very hard. Its much the same for shattered pots as for the cogs of great machines. Until youve seen some of the rest, you cant make sense of any part.

1.1 The Agents of the Mind

Good theories of the mind must span at least three different scales of time: slow, for the billion years in which our brains have evolved; fast, for the fleeting weeks and months of infancy and childhood; and in between, the centuries of growth of our ideas through history.

To explain the mind, we have to show how minds are built from mindless stuff, from parts that are much smaller and simpler than anything wed consider smart. Unless we can explain the mind in terms of things that have no thoughts or feelings of their own, well only have gone around in a circle. But what could those simpler particles bethe agents that compose our minds? This is the subject of our book, and knowing this, lets see our task. There are many questions to answer.

Function: How do agents work?

Embodiment: What are they made of?

Interaction: How do they communicate?

Origins: Where do the first agents come from?

Heredity: Are we all born with the same agents?

Learning: How do we make new agents and change old ones?

Character: What are the most important kinds of agents?

Authority: What happens when agents disagree?

Intention: How could such networks want or wish?

Competence: How can groups of agents do what separate agents cannot do?

Selfhess: What gives them unity or personality?

Meaning: How could they understand anything?

Sensibility: How could they have feelings and emotions?

Awareness: How could they be conscious or self-aware?

How could a theory of the mind explain so many things, when every separate question seems too hard to answer by itself? These questions all seem difficult, indeed, when we sever each ones connections to the other ones. But once we see the mind as a society of agents, each answer will illuminate the rest.

1.2 The Mind and the Brain

It was never supposed [the poet Imlac said] that cogitation is inherent in matter, or that every particle is a thinking being. Yet if any part of matter be devoid of thought, what part can we suppose to think? Matter can differ from matter only in form, bulk, density, motion and direction of motion: to which of these, however varied or combined, can consciousness be annexed? To be round or square, to be solid or fluid, to be great or little, to be moved slowly or swiftly one way or another, are modes of material existence, all equally alien from the nature of cogitation. If matter be once without thought, it can only be made to think by some new modification, but all the modifications which it can admit are equally unconnected with cogitative powers.

Samuel Johnson

How could solid-seeming brains support such ghostly things as thoughts? This question troubled many thinkers of the past. The world of thoughts and the world of things appeared to be too far apart to interact in any way. So long as thoughts seemed so utterly different from everything else, there seemed to be no place to start.

A few centuries ago it seemed equally impossible to explain Life, because living things appeared to be so different from anything else. Plants seemed to grow from nothing. Animals could move and learn. Both could reproduce themselveswhile nothing else could do such things. But then that awesome gap began to close. Every living thing was found to be composed of smaller cells, and cells turned out to be composed of complex but comprehensible chemicals. Soon it was found that plants did not create any substance at all but simply extracted most of their material from gases in the air. Mysteriously pulsing hearts turned out to be no more than mechanical pumps, composed of networks of muscle cells. But it was not until the present century that John von Neumann showed theoretically how cell-machines could reproduce while, almost independently, James Watson and Francis Crick discovered how each cell actually makes copies of its own hereditary code. No longer does an educated person have to seek any special, vital force to animate each living thing.

Similarly, a century ago, we had essentially no way to start to explain how thinking works. Then psychologists like Sigmund Freud and Jean Piaget produced their theories about child development. Somewhat later, on the mechanical side, mathematicians like Kurt Godel and Alan Turing began to reveal the hitherto unknown range of what machines could be made to do. These two streams of thought began to merge only in the 1940s, when Warren McCulloch and Walter Pitts began to show how machines might be made to see, reason, and remember. Research in the modern science of Artificial Intelligence started only in the 1950s, stimulated by the invention of modern computers. This inspired a flood of new ideas about how machines could do what only minds had done previously.

Most people still believe that no machine could ever be conscious, or feel ambition, jealousy, humor, or have any other mental life-experience. To be sure, we are still far from being able to create machines that do all the things people do. But this only means that we need better theories about how thinking works. This book will show how the tiny machines that well call agents of the mind could be the long sought particles that those theories need.