Table of Contents

Guide

L IKE ALL SCHOLARSHIP, THIS WORK WOULD HAVE been impossible without the previous work of many scholars, whose work I have used. My citations reflect my deep debt to these many men and women. I am especially indebted to Eric Kurlander, Charles Bellinger, Richard Ravalli, Tom Johnson, Kelly Gonser, Eric Nystrom, Caleb Hampton, and Derek Cowell, who read the manuscript and provided helpful comments. I appreciate Randy Bytwerk for helping me with a couple of the illustrations. Thanks also to Julie Reuben for her help in obtaining obscure sources through Inter-Library Loan. Thanks to California State University, Stanislaus, for providing a research leave to complete this project. I also thank my agent, Steve Laube, and the Regnery History editor, Alex Novak, for believing in the value of this book project and for bringing it to publication. Most of all, thanks to my dear wife and my precious children for their love and support.

W HILE MOST PRIMARY SOURCES ON HITLERS religion are relatively uncontroversial, a few are contested, especially individuals memoirs and personal recollections of conversations with Hitler. When confronted with sources that some scholars consider problematic, my policy has been either not to use them at all, or else only to use them when the point they are making is confirmed by a good deal of independent testimony. Occasionally I may mention a well-known source I consider unreliable or only partly reliable to take issue with its claims.

The authenticity of most of Hitlers speeches and writings are uncontroversial, and I use them liberally. However, some have questioned Hitlers Table Talks as a reliable source for discovering Hitlers views on religion. In an interesting piece of detective work, Richard Carrier demonstrates convincingly that the English version of Hitlers Table Talk is based on the translation of a problematic and possibly inauthentic text. Thus, I do not use nor cite the English translation of Hitlers Table Talk. However, even Carrier admits that the two German editions edited by Henry Picker and Werner Jochmann are generally reliable. Carrier was hoping that debunking Hitlers Table Talk would demolish the image of Hitler as an anti-Christian that many scholars have built on this flawed document. Unfortunately for Carrier, Hitler is every bit as anti-Christian in the Jochmann and Picker editions.

The Picker and Jochmann editions of Hitlers Table Talk monologues are very similarindeed verbatimin many passages. Each contains some passages not found in the other one. However, when comparing the many passages they share in common, most of them are identical, though occasionally there are very minor differences. Oddly, Carrier maintains that Picker is probably more reliable than Jochmann, but this is not the opinion of most scholars. I have read both editions and will rely mostly on Jochmann, though many of the passages I quote are in both editions. I will only use Picker sparingly and to confirm points Hitler made elsewhere, not to try to establish some unique point. We also need to remember that these monologues are not transcriptions of Hitlers talks, but are reconstructions based on notes taken during the monologues. Based on some testimony of those present at these monologues, the renditions we have are generally accurate, since they were written immediately afterwards.

The only book Hitler published during his lifetime, Mein Kampf, poses a different kind of problem. It is notoriously unreliable as a memoir, and many scholarsmyself includedconsider some of the vignettes about his earlier life completely fictitious. It does, however, accurately convey Hitlers ideology, as does Hitlers Second Book, which was only discovered after World War II.

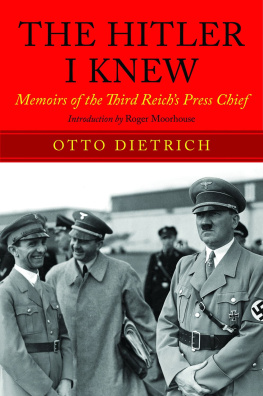

Two other contemporary sourcesJoseph Goebbels diaries and the recently recovered Alfred Rosenberg diariesconfirm the general account of Hitlers monologues. My book is one of the first to use Rosenbergs diaries, which do not divulge anything that overturns our previous knowledge about Hitler, but rather corroborate other sources and provide some interesting details. While memoirs by Hitlers associates are important sources, some were written before 1945 by erstwhile friends and allies who had turned against Hitler. Often they had an axe to grind and wanted to protect their own image. Others were written after 1945 by those who wanted to distance themselves from Hitlers views. I have examined a large variety of accounts by everyone from Hitlers secretaries to Hitlers architect friend Albert Speer to Hitlers political cronies, Hans Frank and Alfred Rosenberg. While there are some contradictions between these various accounts, they generally agree on the general outlines of Hitlers religion.

Probably the most controversial piece of memoir literature about Hitlers religion has been Hermann Rauschnings writings. Some historians, such as Theodor Schieder, have defended Rauschning from his dismissive treatment by other historians (such as Eberhard Jckel). I have taken Rauschnings perspective into account, and even if his conversations with Hitler were completely accurate, it would have little effect on my interpretation. In this book, I acknowledge Rauschnings position when relevant, but ultimately I do not consider his writings reliable enough to use extensively.

Another controversial source containing an extensive conversation with Hitler about religion is Dietrich Eckarts Der Bolschewismus von Moses bis Lenin: Zwiegesprch zwischen Adolf Hitler und mir (1924). I use Eckarts work to illuminate Eckarts position and also the religious perspectives in Hitlers milieu, but I do not consider it a reliable source for Hitlers own words on religion. In 1932, the Nazi propaganda leadership denied that Eckarts book was reliable, calling the recorded conversations a fictional fantasy. The Nazis at that point were combating those who were using Eckarts book to demonstrate that Hitler was anti-church. But even if Eckarts work were a verbatim account of Hitlers words, it would merely reinforce my interpretation of Hitlers religion.

Concerning Hitlers secretaries testimony, Christa Schroeder claims that Albert Zollers book, Hitler privat, was based on interrogations with her, but Zoller added a significant amount of material from other sources and may even have invented some of it. Since Schroeder disputes its reliability, I have not used Zoller. Instead, I have relied on Schroeders own work, Er War Mein Chef: Aus dem Nachlass der Sekretrin von Adolf Hitler. Much of her testimony is also confirmed by Traudl Junge. Unfortunately, one crucial paragraph in Junges memoirs that discusses Hitlers religion and Hitlers belief in human evolution is cribbed from Schroeders earlier book. Junge had a co-author, so I do not know which one of them plagiarized. Because of this problem, however, I have used Schroeder instead of Junge, even though they both say essentially (and sometimes exactly) the same thing.

One final questionable source that makes a difference in interpreting Hitlers worldview is The Testament of Adolf Hitler: The Hitler-Bormann Documents, FebruaryApril 1945. The editor, Francois Genoud, was the same figure Carrier criticized for his mishandling of the Table Talk manuscripts. In this case, Genoud claimed that he translated this

Next page