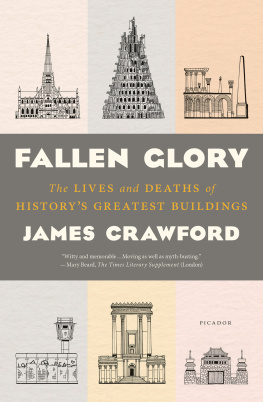

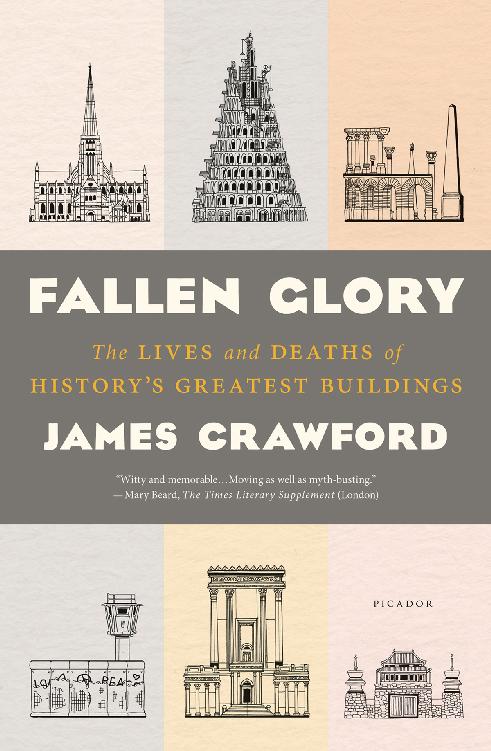

F ALLEN G LORY

The Lives and Deaths of Historys Greatest Buildings

James Crawford

Picador New York

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: http://us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Several years ago I visited the ruins of the palace complex of Knossos on the island of Crete. It was an early morning in September, but the sun was already very hot, and the surrounding olive groves throbbed with the scratching of the cicadas. I had just smashed my big toe against an ancient and well hidden flagstone, and was bleeding profusely into the ground: my inadvertent offering to a site that archaeologists believe was once used for human sacrifice. I liked to imagine I might be standing somewhere within the labyrinth built to hold the infamous mythological resident of Knossos the Minotaur. Had I been one of the Athenian youths sent to feed the monster, I would have been in big trouble: limping through the maze in my cheap, plastic flip-flops, leaving a trail of blood in my wake. At the northern fringe of the ruins, I could see a broken chunk of portico propped up by three columns, each painted a deep orange. On the wall behind the columns, a bright fresco showed a bull bending its head to charge. This is one of the iconic show-pieces of the site, a fragment framed in a million tourist photographs, including my own. And it is a fake.

In 1900, the English archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans bought the entire site of Knossos and its surrounding land. He embarked on a massive programme of excavations, and then began what he called his reconstitutions. There is nothing ancient about the portico. It is, in fact, one of the very first reinforced concrete structures built on Crete, and its construction was overseen by Evans himself.

Evans has come in for a great deal of criticism over the years. Some say he was carried away by his passion for classical mythology and lost track of his duties as historian and scientist. The less kind verdict presents him as an odious product of Victorian Britain: egocentric and supercilious, he is accused of creating a skewed account of the origins of Cretan civilisation that was more about his own repressed sexuality than the actual archaeology. I suspect Evans would never make my personal dinner party dream team how do you cater for someone who, throughout his time on Crete, continued to import his food by the crate-load from England, and refused to drink the local wine? but I cant help but feel some affinity with what he was trying to do at Knossos. After uncovering the remains of a building situated at the centre of one of the ancient worlds most significant cultures, Evans wanted to go further still. I think of him standing among the excavation works, looking out at the surrounding amphitheatre of green, terraced hills, letting his mind wander back to the mid-second millennium BC. He wanted to know the story of this great palace. How was it born and how did it die? Who were its kings, princes and queens? What did they believe in? What was the basis of their faith? What formed the inspiration for their wondrous art? Evans response to these questions was perhaps extreme and ill-judged, but I cant fault his enthusiasm. I feel the same whenever Im confronted by a ruin, or by a story that begins where you are standing now there was once The scattered stones are not enough for me. I want to rebuild these fallen glories in my minds eye and let them live again.

I have experienced this sensation in a number of places around the world. I remember climbing the steps of the Paris Metro at the Place de la Bastille, to be greeted by a blast of car horns and a buzz of scooters. I took a seat at a pavement caf and looked out over a roundabout and past a bronze freedom column to the glass and stone bulk of the Opra National. But there was no trace of the Gothic fortress-prison that once provoked a revolution. The only remaining fragment of dissident spirit I could spot was some anti-Sarkozy graffiti, high on an apartment wall.

In London, I have crossed the Millennium Bridge from the Tate Modern many times. Faced with Wrens masterpiece, I cant help but picture a different city skyline. If the Pudding Lane bakers had been less cavalier about fire safety, would Old St Pauls, one of the largest, most venerable and most ramshackle medieval Cathedrals in Europe, still crown Ludgate Hill in place of todays iconic, baroque dome?

Once, on a summer road trip through Andalucia as we drove west out of Cordoba, a Spanish friend pointed through our windscreen across a grass plain towards a complex of stone buildings in the foothills of the Sierra Morena. These were, he told me, the remains of one of the greatest palaces in Spanish and world history, the Madinat al-Zahara. It was early evening and, with the sun dipping, we took a detour to the ruins. The battery in my digital camera was dead, but I can still see in vivid detail the low light turning the stones red and the dramatic panorama across the plain. I imagined the last caliph enjoying this same view a thousand years earlier perhaps just days before a civil war erased this dream palace forever.

There is no question that we invest our greatest structures and constructions with personalities. We care about buildings sometimes, perhaps, more than we care about our fellow human beings. We shout with joy when we raise them up; we weep with sorrow when we destroy them. And, of course, we do continue to destroy them buildings young and old, all over the world.

Even the longest human life barely exceeds a century. How much more epic are the lives of buildings, which can endure for thousands of years? Unlike the people who made them, these structures experience not just one major historical event, but a great accumulation of them, in some cases stretching all the way from the prehistoric era to the present day. In its lifetime, the same building can meet Julius Caesar, Napoleon and Adolf Hitler. What human could claim the same? If we let them, buildings have the potential to be the ultimate raconteurs. These are some of their stories.

My visit was before the Je suis Charlie marches in January 2015, since when the Place de la Bastille has once again been covered in dissident messages.

Are the gods architectures greatest patrons, or its greatest enemies? Much has been built in their names. Just as much very likely a great deal more has been destroyed. Perhaps this is not surprising. What are gods if not the original architects? And there is, after all, nothing one architect dislikes more than the work of another

Humanitys first great building myth is a case in point. The Tower of Babel was, it seems, sent to development hell by a god piqued at the audacity of his human creations. Yet even when plans have been handed down directly from heaven, the course of architecture has rarely run smooth. Time and again blueprints produced by divine hands have been misinterpreted by mortal masons. The gods have first commissioned and then abandoned some of their greatest works, from a palace in the hills of a Mediterranean island to a city on a desert plain on the banks of the Nile. These buildings have been inhabited and destroyed by a unique cast of heroes and villains some imagined, others frighteningly real.

There is one place, however, that the gods have never yet left alone. A hilltop inside a city in an arid Middle Eastern landscape, where a great temple was built, demolished, rebuilt and then burnt to the ground, has become the setting for historys longest running property dispute. A dispute so intractable, some say, that it will only be resolved by the end of the world.