The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Introduction

T he innerwhat is it?

if not intensified sky, hurled through with birds and deep with the winds of homecoming.

RAINER MARIA RILKE

One of my closest mentors, the late Ray Worring, used to take me on long drives through the wilderness areas of Montana. After one such drive Ray suggested I spend some time looking out over the mountain range. Even though the view was extraordinary, I began to balk at the discomfort of sitting in the freezing wind, numbed to the bone with cold. For what purpose had we come so far simply to sit and look at a mountain? It took many years before I understood the message he wished to impart that early-spring day: You are this vastness. This vista you see, this grandeur, this enduring strengthif you go deeply enough inside yourself, you will find not something small but something immensely spacious. This is the essence of the human spirit. This message, imparted so simply and yet ineffably etched into my experience of myself and the world, had an enormous influence in shaping what I came to see as the purpose of yogato reconnect to the original vastness and silence of the mind. And it was integral to Rays teachings that this understanding of oneself be not only an intellectual idea but a felt cellular experience in the body.

In the early sixties, when yoga became popular through the work of Richard Hittleman and other such luminaries, the teachers of that time had to find a way to make an Eastern science and art palatable to the western mind. This was no easy task. Most presented yogas tangible formsthe postures and the more pragmatic breathing exercises. These forms the Western mind could easily grasp. Others presented the esoteric aspects of yoga in teachings that reached few and were understood by even fewer. Form is what the Western mind could understand, and so it was the forms of yoga that were emphasized. In an effort to popularize yoga the more essential spiritual message of the practice has been pared away and oftentimes completely eliminated.

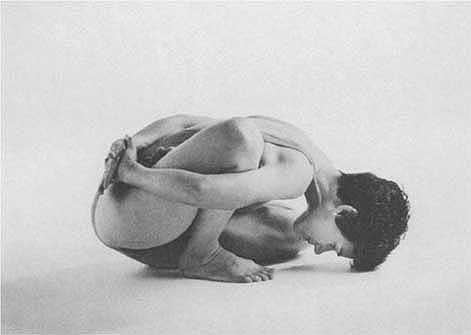

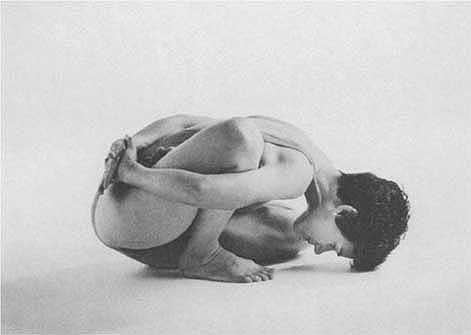

Increasingly doing good yoga has come to mean having a beautiful body, remaining forever youthful, and being able to show ones adeptness through the seemingly solid evidence of advanced postures. But as we stretch our muscles deeply or strengthen our abdominals, are we coming closer to feeling a deep peacefulness within ourselves and an inner equanimity that can meet the challenges of life in a compassionate and skillful way? Like the botanist who finally breeds the perfect rose only to discover that in the process he has lost the fragrance of the bloom, when we strip yoga to its mechanics, we also lose something essential. The task of todays teachers and students is to reclaim the essential spirit and intention behind these practices in a way that challenges rather than placates the underpinnings of this Western mind. For it is this change of mind that is so desperately needed to bring about healing in the world today.

I have been as guilty as any of both practicing and teaching yoga in a way that made the postures and practices more important than the spirit of the person practicing them. My early obsession with perfecting the forms of yoga brought with it a greater and greater sense of unease and inner dissatisfaction. The realization that I had bought into the dictum of a culture obsessed with achievement and the unhappiness wrought by such striving led me to a long period of deep experimentation in my own practice. Through the generosity and willingness of my students to join me in this inquiry, I have slowly uncovered a more natural way of discovering the essence of the practice through form. The forms then become vehicles for experiencing ones essential nature rather than goals in and of themselves. Then whether you attain any particular posture becomes irrelevant. The shift from dominating, controlling, or ignoring nature to listening and working with natures wisdom marks the beginning of this change of mind. When We shift from being the mover to letting life move through us, we make the first step toward surrendering our heart to spiritual practice. This step marks the beginning of yoga as a life path rather than a form of sophisticated calisthenics. I am convinced that there is nothing new about this approach and that it can best be described as a neoclassical revival of the original way of working first explored by yogis centuries ago. I am equally convinced that anyone who becomes quiet enough to observe the way of nature will arrive at conclusions similar to my own. The ancient teachings of Yoga, and others such as Taoism, Buddhism, and Ayurveda all spring from the same universal source of wisdom.

My teacher, Ray, encouraged me to work with the body in the service of regenerating the connection to the spirit. So this book is my gift to those who would wish to reunite with their spiritual life through the body. Observing, perceiving, feeling, and acting from the wisdom of the natural world is nonetheless a long apprenticeship. Even the very idea of apprenticeship is a foreign one in the face of a society compelled to follow anything that offers immediate gratification. But the slowness of this path is part of the healing. It is part of finding ones place in the rhythm of life again. This reunification with nature lies at the heart of the true healing power of yoga practice. Through that practice we can become peaceful, we can experience ease with ourselves and others, and ultimately we can create a society that values such things. Then as we advance in our yoga practice, we will realize that however far we go, we are always in the process of returning to this natural self.

Donna Farhi

May 2000

Acknowledgments

Many people nurture the creation of a book, the least of whom are the poor fellows who must live with the writer through the often difficult and cantankerous period of gestation. My partner, Mark Bouckoms, has been one such fellow, buffeting the thick and the thin of it with me and offering enormous support in the way that only good friends can.

I am tremendously grateful to my past and present mentors and teachers who have, through their own practice and commitment, inspired my love for yoga. Among these are Jim Spira, Judith Lasater, Angela Farmer, Dona Holleman, and many others who were faculty at the time of my training at the Iyengar Yoga Institute in San Francisco. Although I have had few opportunities to study personally with Bonnie Bainbridge Cohen, her writings and teachings as taught through Body-Mind Centering practitioners and colleagues such as Lynne Uretsky have been central to helping me find a physical language for helping others experience the totality of the body.

My nascent years as a writer for Yoga Journal were particularly fostered by one caring editorLinda Cogozzo. Without her encouragement I daresay I would never have ventured to commit myself to the printed word. The journal itself has throughout my career spurred me to crystallize my thoughts and thus has been a central means of sharing my ongoing research with the worldwide yoga community.