Of Sand or Soil

PRINCETON STUDIES IN MUSLIM POLITICS

Dale F. Eickelman and Augustus Richard Norton, series editors

A list of titles in this series can be found at the back of the book

Of Sand or Soil

GENEALOGY AND TRIBAL BELONGING IN SAUDI ARABIA

Nadav Samin

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 2015 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press,

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press,

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

Jacket art: With permission from Abd al-Ramn al-Shuqayr,

Alas Mushajjart Ban Zayd (Abd al-Ramn al-Shuqayr, 2015)

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Samin, Nadav, 1976

Of sand or soil : genealogy and tribal belonging in Saudi Arabia / Nadav Samin.

pages cm.(Princeton studies in muslim politics)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-691-16444-1 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. TribesSaudi Arabia. 2. Tribal governmentSaudi Arabia. 3. Saudi ArabiaEthnic relations. 4. Jasir, Hamad. I. Title.

DS218.S26 2015

953.805dc23

2014044326

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Linux Libertine O and Adobe Caslon Pro

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

For Lily and Selma

Contents

Illustrations

MAP AND TABLE

Acknowledgments

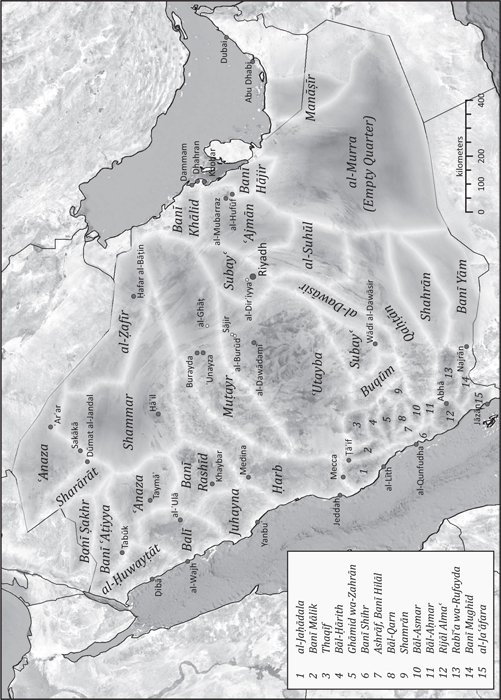

T his book would not exist without the following people: Bernard Haykel, who combines two qualitiesgenerosity and learnednessuncommon in a single person; Michael Cook, whose mastery of both the grand and the intimate movements of history inspired this study; Isabelle Clark-Decs, who, by sharing generously her knowledge and time, made the process of writing this book a true joy; and Michael Laffan, who provided insightful feedback and support throughout the writing and editing of my early drafts. I would also like to thank Andras Hamori for helping me translate and interpret some of the poems included here, and Jonathan Chipman for his skill and patience in producing the map.

I thank the family of amad al-Jsir for their generosity and openness with a stranger; Maan and May, I am in your debt. I also cannot forget my friends at the amad al-Jsir Cultural Center, who greatly aided my research. I extend my gratitude to the King Faisal Center for Research and Islamic Studies, and to Prince Turki al-Faisal, Yahya b. Junayd, and Awadh al-Badi in particular, for graciously hosting me during my visits to the kingdom.

I acknowledge here the many Saudis who have advocated for my project, lent their expertise, or opened their homes and personal histories to me, including Nasir al-Hujailan, for his strong advocacy; Khaled Radihan, for educating me in the field; Fyiz al-Badrn, for his patience and generosity with a genealogical novice; Abd al-Ramn al-Shuqayr, for his unparalleled support and kindness; Saud al-Sarhan, for his friendship and hospitality; Ab-dallh al-Munf; Fahd al-Semari; Fahd al-Sahl; Mushawwi al-Mushawwi; Amad; the people of al-Ul; and countless others.

I am sincerely grateful to Abdulaziz Al Fahad, Saad Sowayan, and the anonymous reviewers of the manuscript for their careful attention and valuable feedback. A number of other scholars lent their time and energies to book chapters or their precursors, including Steve Caton, Lawrence Rosen, Engseng Ho, Andrew Shryock, Dale Eickelman, Pascal Menoret, Amaney Jamal, Muhammad Qasim Zaman, and Cyrus Schayegh. This study owes a particular debt to the rich and innovative works of Andrew and Engseng, without which it would not exist.

I extend gratitude to Fred Appel, Sara Lerner, Dimitri Karetnikov, Juliana Fidler, and Bhisham Bherwani at Princeton University Press for helping guide this project to completion.

I thank my parents, Ami and Rena, and my sister, Bali, for their belief in me. Lastly, this book is dedicated to Lily, for your love, support and encouragement throughout the writing of this book, and to Selma, with whom weve now begun our own family tree.

My research in Saudi Arabia was supported by fellowships and grants from the Social Science Research Council Postdoctoral Fellowship for Transregional Research with funds provided by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation; the Princeton Center for Arts and Cultural Policy Studies; the Project on Middle East Political Science; the Princeton Institute for International and Regional Studies; and the Near Eastern Studies Department at Princeton University.

Note on Transliteration

I adopt a modified International Journal of Middle East Studies (IJMES) system of transliteration. As this study is in many respects about names and naming practices, all Arabic names and most other proper nouns have been rendered with full diacritical markings. Exceptions are commonly invoked terms such as Saudi, Wahhabi, Salafi, Najdi, and Hijaz/Hijazi, as well as common Arabic terms that have entered the English lexicon (e.g., imam, Sufi, Shia). My transliterations of dialect poetry and other dialect terms from central Arabia and neighboring regions aspire less to linguistic precision than to establishing the visceral presence of Arabias oral culture as a backdrop to this study.

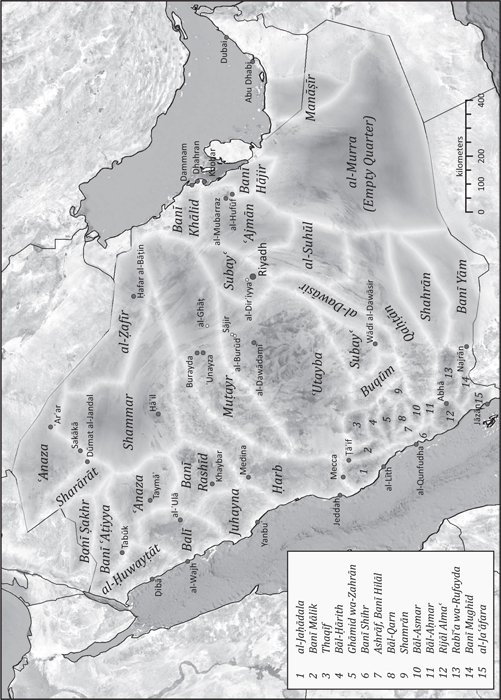

Map 1. Approximate boundaries of Arabian tribal territories before the establishment of the modern Saudi state, along with toponyms significant for this study.

Of Sand or Soil

Introduction

It is not for the truth that men seek, but for that which is pleasant to believe. Poor, ill-clad, shivering truth stands pitiful by the way; for men have ever passed her by in search of that which they desire.

J. Horace Round

A ustere and fortress-like, the Saudi Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Riyadh was built to inhabit its central Arabian surroundings. Wrapped around the massive front gate of the Danish-designed building is a Quranic verse, 49:13: O people, we have created you male and female, the inscription begins, ascending toward the right end of the lintel in flowing, golden script. Bearing left above the tall, recessed doorway, the verses key phrase unfolds across the observers field of vision: and made you peoples and tribes. Descending to completion down the left side of the door frame, the inscription concludes: so that you may come to know one another. Verily, the most noble among you is the most God-fearing.

Invoked in this context, verse 49:13 is a statement of bureaucratic purpose, reminding visitors that the Foreign Ministrys mission to contribute to the formation of an international order based on justice and principles of common humanity rests upon the Saudi states pious foundations. Immutable associations aside, it is to the peoples or nations of the world, not to its tribes, that the Foreign Ministry addresses itself. For an alternative reading of this verse, one might look to its presentation as a more figurative framing device for the thousands of genealogical trees that have been conceived and created by Saudis over the past half-century. Splashed across the top border of that quintessential Saudi art form is, quite often, verse 49:13. O people, we have created you male and female, and made you peoples and tribes, so that you may come to know one another. Verily, the most noble among you is the most God-fearing. Positioned above a family tree, the verse takes on a radically new meaning. Its call for the mutual acquaintance of nations is muted, as is its apparent privileging of Muslim communion over the fractured and particularist identities into which humanity has been arrayed. In this colorful and allusive statement of modern Saudi identity, the nations of the world, as its God-fearing people, recede into the background, and the Qurans indirect endorsement of tribal belonging becomes the central fact of the verse and its invocation.

Next page