CONTENTS

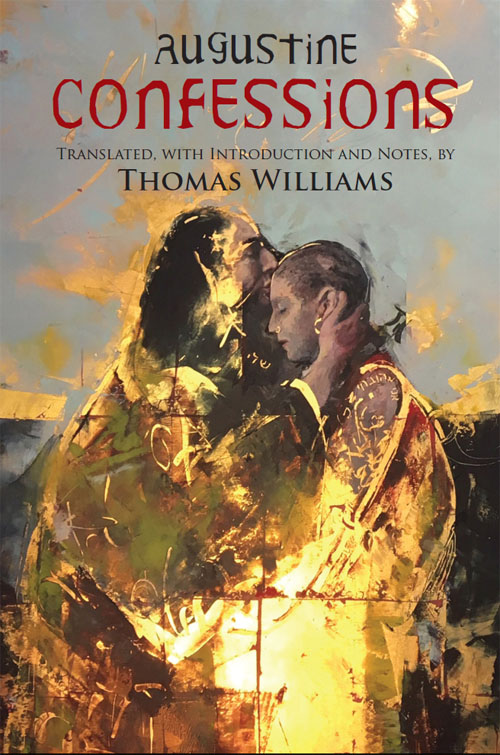

Augustine

CONFESSIONS

Augustine

CONFESSIONS

Translated, with

Introduction and Notes, by

Thomas Williams

Hackett Publishing Company, Inc.

Indianapolis/Cambridge

Copyright 2019 by Hackett Publishing Company, Inc.

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

22 21 20 19 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

For further information, please address

Hackett Publishing Company, Inc.

P.O. Box 44937

Indianapolis, Indiana 46244-0937

www.hackettpublishing.com

Cover design by Brian Rak

Interior design by Elizabeth L. Wilson

Composition by Aptara, Inc.

Cataloging-in-Publication data can be accessed via the Library of Congress

Online Catalog.

ISBN-13: 978-1-62466-783-1 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-1-62466-782-4 (pbk)

ePub3 ISBN: 978-1-62466-801-2

Anselm, Basic Writings . Translated, with Introduction, by Thomas Williams.

Thomas Aquinas, The Treatise on Happiness The Treatise on Human Acts . Translated and Introduced by Thomas Williams. Commentary by Christina Van Dyke and Thomas Williams.

Augustine, On Free Choice of the Will . Translated, with Introduction, by Thomas Williams.

{v} Contents

The page numbers in curly braces {} correspond to the print edition of this title.

{vii}

The Confessions is a prayer: a prayer of avowal, a prayer of thanksgiving and praise, and a prayer of repentance. For these are the three meanings of the Latin verb confiteor , of which confessio is the noun form.

To confess is to avow or acknowledge, as in the hymn Te Deum laudamus , We praise thee, O God: we acknowledge ( confitemur ) thee to be the Lord, and the Nicene Creed, We acknowledge ( confitemur ) one baptism for the forgiveness of sins. To confess is to offer thanks and praise, a usage very frequent in Augustines Psalter: for example, Give thanks ( confitemini ) to the Lord, for he is good, for his mercy endures for ever (Psalm 117:1). And to confess is to admit to ones own sin, as in 1 John 1:9: If we confess ( confiteamur ) our sins, God, who is faithful and just, will forgive us our sins and cleanse us from all unrighteousness.

In some ways, the last aspect of confession is the least important of the three in the Confessions , a disappointment for those who go to the work expecting lurid tales of past sin and find instead something rather different. And confession of sin is, in any event, not separable in Augustines mind from avowal and thanksgiving: for to acknowledge our faults is to acknowledge the goodness of the nature that God has given usit is he that hath made us, and not we ourselves and to give thanks that God is making us what we long to be.

Accordingly, the Confessions is also the history of a life: a life granted by God, desperately mismanaged by Augustine, and then brought into order by the God who was always present even as Augustine, like the prodigal son in the parable of which he is so fond, ran away from God into a far-off country, a land of unlikeness. It is three histories, really, because the story of Augustines own life opens up into the story of creation, given being, form, and order by the same God who made and then remade Augustines life, and the story of creation in turn opens up into an allegory of the life of the Church.

The complexity of these three interwoven histories requires some elucidation, and that is what I attempt to provide in this Introduction. I begin with a brief account of Augustines life and then turn to a reading of the Confessions that attempts to illuminate its structure and provide a framework in which to make sense of its diverse themes. I conclude with a discussion of Augustines use of Scripture, the most important unifying feature of the Confessions .

{viii}

By the time Augustine started writing the Confessions in 397 AD, he had been a priest at Hippo Regius (now Annaba in Algeria) for six years and bishop for one or two. He had not sought ordination, preferring a quiet life of ascetic discipline and philosophical contemplation; but ordination was forced on him, and he found himself not only a teacher, preacher, and minister of the sacraments, but also (especially as bishop) a judge, public figure, and controversialist. The prodigiousness of Augustines literary outputtwo hundred years later, Isidore of Seville would say that anyone who claims to have read all of Augustine must be a liaris all the more remarkable when we consider how busy he was, how many claims there were on his time.

Augustine was born on 13 November 354 in Thagaste (modern Souk Ahras), about sixty miles south of Hippo Regius. His father, Patrick,

The profession in question was rhetoric. All his education was meant to make him into a successful rhetorician: a salesman of words (9.5.13), as he describes it dismissively from the perspective of someone whose life has been radically reoriented around quite different aims. And he did succeed, accent or no, before he gave up his career and turned to the life of Christian philosophical contemplation that he was not destined to enjoy for very long. The story of Augustines life as we have it in the Confessions is the story of how he pursued that career, and along the way pursued other thingssensual gratification, knowledge, influenceuntil at last he gave in to the God who had been pursuing him, and who became his one true and enduring love.

That part of the story I do not need to retell here, because you have it before you in the Confessions . But Augustine would live another thirty-three years after he began to tell that story,

411 would prove to be a consequential year in other ways. The connections he made at the conference made him aware of ideas and debates that would shape much of the rest of his career. He heard from the imperial commissioner, Marcellinus, that some Roman aristocrats were blaming Christians and their God for the decline of Rome, which had been sacked by the Visigoths the year before. Augustine worked on his response for the next fifteen years. He called it On the City of God against the Pagans ; we generally know it simply as The City of God . Next to the Confessions it is Augustines most widely read work. There are two cities, he says, founded on two loves: the city of God, founded on love for God to the point of contempt for self, and the city of the devil, founded on love for self to the point of contempt for God. The city of God is not the Church, and the city of the devil is not the state: there are people within the visible Church who do not belong to the city of God, and the state can be an instrument of Gods providential governance, though no earthly authoritynot even the great and glorious Romeis anything more than a temporary arrangement, destined, as all things this side of eternal peace are destined, to pass away.

Marcellinus also made Augustine aware of the ideas of Pelagius and his disciple Caelestius. At least as Augustine understood the matter (a qualification I introduce in order to sidestep historical arguments about the exact character of Pelagian teaching), Pelagians taught that human beings retain the free will necessary to lead a morally good life without any need for divine grace. Adams fall damaged only himself; it was not transmitted to the rest of the human race, except insofar as Adam set a bad example. There is therefore no such thing as original sin, and infants are born in the same state Adam was in before the fall; infant baptism is accordingly unnecessary. {x} Just as Adam could have done, all human beings can, by our own free choice, resist sin and live righteously. Augustine was particularly horrified to find an earlier work of his own, On Free Choice of the Will , quoted in support of such views; he devotes quite a bit of space in his later Reconsiderations to showing that On Free Choice of the Will was anti-Pelagian even before he knew there was such a thing as Pelagianism. The polemic against Pelagianism would occupy Augustine for the rest of his life, leading himthis much, I think, is uncontroversialinto increasingly stark portrayals of the damage of original sin and the wretchedness of the human condition apart from grace. But the seeds were there long before, and we see them clearly in the Confessions , from the discussion of infant sinfulness in Book 1 to the pervasiveness of the idea that it was Gods initiative, not Augustines own, that won Augustine for God.