Contents

Guide

Contents

- PART ONE

ADDING WOOD TO THE FIRE - PART TWO

RETURNING HOME

Foreword

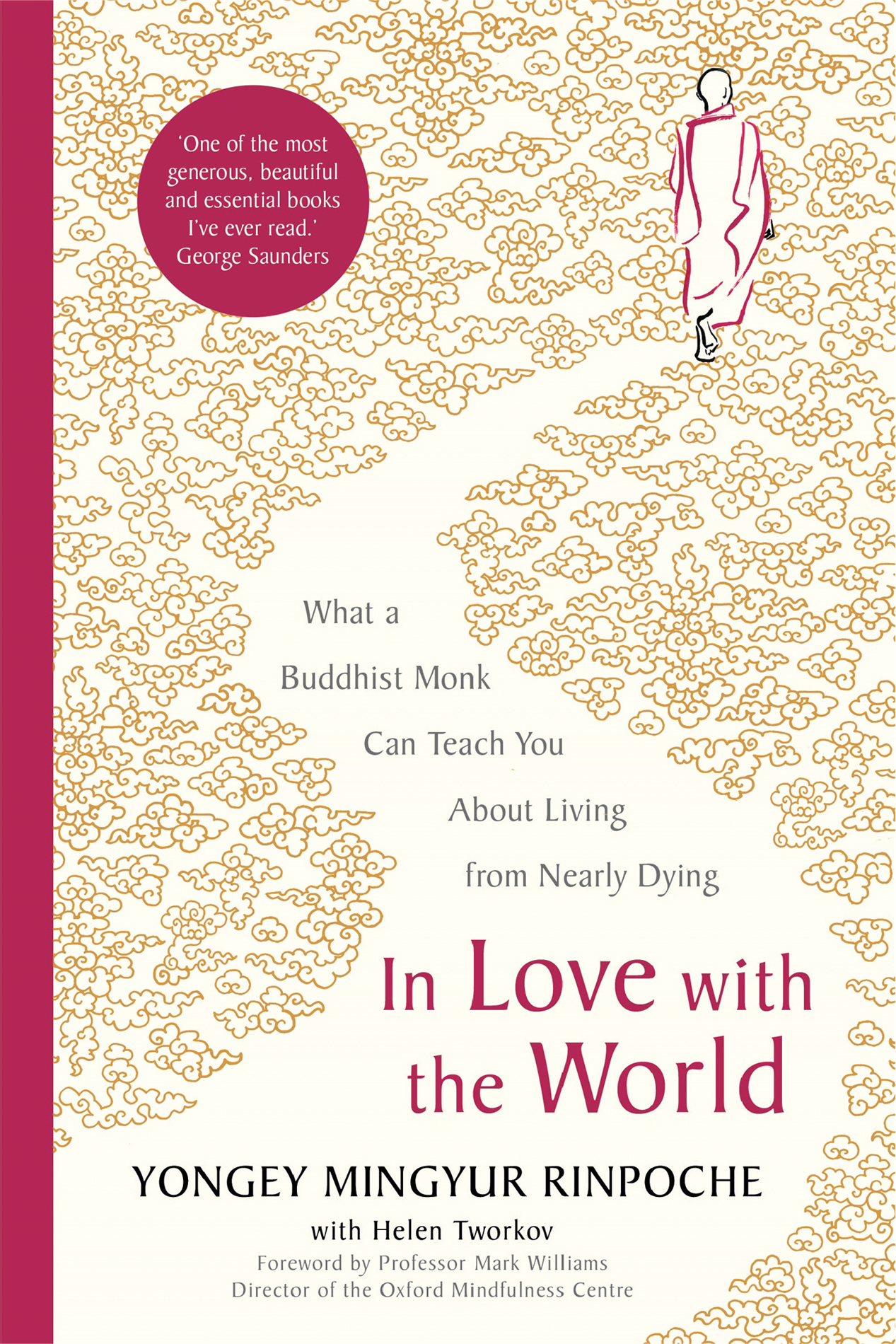

BY PROFESSOR MARK WILLIAMS

T HIS IS A REMARKABLE book. It is at once a travel book, a spiritual guidebook and a thriller. It is a travel book because it describes a journey away from the safety of a monastery into a self-imposed wandering exile. It is a spiritual guidebook because for anyone who pursues wisdom through meditation practice every page has a profound insight, expressed through the events that take place, the parables these bring to mind and the reflections offered. It is a thriller because what Mingyur Rinpoche finds is that each day brings discoveries that are very different from his expectations for the journey. It is far more unpredictable, even dangerous, and it becomes impossible to read very far without caring deeply about whats going to happen next.

And at every level it is a meditation on bardo: the experience of being in transition. Bardo can be understood both as the gap between death and rebirth, and also as the transition between the death of any moment and the rebirth of the next. Because the present moment is always a transition between the past and future, we can use it to learn the skill of letting go of those habits of mind that hinder us from allowing any transition to take its course. This is what meditation can do for us.

Whether we train the mind by using our breath, or using pain, or doing compassion exercises, every practice is about waking up and becoming conscious of a universal reality that transcends the contents of our individual minds.

Notice the implication of this: that meditation is much more than learning to pay attention, important though this is. Yes, paying attention especially to the body is the foundation of the path. It gradually helps us to build on that foundation: to discover an open-hearted awareness that gives us the courage to see beyond the habitual petty judgements that so easily rule our lives. Gradually, as we let the preoccupations of the conceptual mind dissolve, we come to see that there are moments, available to us if we are alive to them, in which we glimpse another mode of being. Mingyur Rinpoche shows how this may start by focussing on the short gap between breaths or between thoughts, which may afford a fresh glimmer that startles us into wakefulness. It may only last a moment but that is all we need for now. Noticing the gap introduces us to the mind that does not reach out to grasp a story of loss or love, or to a label of fame or disgrace... It is such disclosure moments that can give deep reassurance that its actually okay to let go of the ego; to see instead an unchangeable awareness in the midst of turbulence.

There is so much in this book, but three things are particularly striking. The first of these is the way in which Mingyur Rinpoche rehabilitates yearning, yes, even craving. This is hugely important. For none of us have to read much Buddhist literature, or practice meditation for very long, before we think we know who the enemy is. Isnt craving the thing that gets us into trouble? Isnt it craving that we need to hunt down and eliminate? But craving is a member of a large family. Yes, there are some members of the family that are generally frowned upon; we may know them as thirst, craving and attachment. There are other, more noble cousins of the family that are more often celebrated: motivation, values and intentions. In the middle are such things as longing and desire that seem to be able to point both ways. When we find ourselves craving material things, or sweet food, or soft comfort, its easy to think that this is wrong, to be rejected and that mindfulness or other forms of meditation will be the way of getting rid of it. Be mindful and you wont crave! But when after many months or years of meditation practice we find ourselves still craving, a deep sigh arises: when will I find the way to rid myself of this?

Mingyur Rinpoche is much kinder: dont try to eliminate anything, including craving. Learn to look, he says. See whats happening here. Thirst, craving, desire, longing these are all different aspects of a deep desire for happiness. Now keep looking, bringing open-hearted awareness to your yearning, and you may gradually begin to see for yourself which things actually cultivate the happiness you seek; which things offer the release from suffering you deeply desire. In this, he expresses again the most profound wisdom of the mystics: keep your thirst before you; for it can give you a source of light, guiding you to the place where life is most richly to be found.

Second, he shows us the nature of our confusion, how our misperceptions turn us into targets. Our attempts to solve our problems can often make things even worse. The more rigid our sense of self, the more surface we provide for the arrows to hit. This is familiar to anyone who practices meditation. There is nothing inherently wrong with the thinking mind: rational analysis to solve problems is what is needed in many situations. But when we are sad or upset, and then begin to analyse and judge ourselves, thoughts can easily become an avalanche of self-blame and despair, in which the mind goes round and round, getting more and more upset.

Why do we become so confused? Mingyur Rinpoches answer is beautifully expressed:

The insight that the Buddha discovered is so simple, and yet so difficult to accept. His teachings introduce us to a dormant, hidden, unrealized part of ourselves. This is the great paradox of the Buddhist path: that we practice in order to know what we already are, therefore attaining nothing, getting nothing, going nowhere. We seek to uncover what has always been there.

Third, his book describes in painful honesty the way that the journey he is making into unknown aspects of the world and unknown aspects of himself is a gradual change from a letting go into a sense of offering up. Although this deep transformation builds on the foundations of long meditation practice with wonderful teachers, it had to be discovered in the messiness and uncertainty of casting himself adrift from all that was familiar. The unfamiliar included not knowing where the next meal would come from, whether it might poison his body or whether death would come too soon for adequate preparation.

Offering up what is most precious is an act that demands everything. It is allowing emptiness from which all arises to return to emptiness. It is an act of sacrifice that is, a moment that makes sacred not by adding something that was missing, but by revealing something that was here all along.

This book shows a way of living life with a grace that blesses all it touches. No one could read it without receiving a gift from every page.

Mark Williams

Emeritus Professor of Clinical Psychology

University of Oxford

Prologue

J UNE 11, 2011

I FINISHED WRITING THE letter. It was past ten oclock on a hot night in Bodh Gaya in north-central India, and right now no one else knew. I placed the letter on a low wooden table in front of the chair that I often sat on. It would be discovered sometime the following afternoon. There was nothing left to do. I turned off the lights and pushed back the curtain. Outside, it was pitch black, with no sign of activity, just as I had anticipated. By ten thirty, I began pacing in the dark and checking my watch.