This book made available by the Internet Archive.

FOREWORD

The voice is unmistakable. Listen:

Fling a note of music upward. It travels undulatingly with a life all its own through dome within dome, from hemicycle to arcade and beyond through unseen corridors and passages high up in the facades, to still farther corners, unexpectedly issuing again in solemn arpeggios, speaking to you as a return message from behind and above and each side. Standing in the south gallery, you find that you are listening not merely to beautiful acoustics. Some voice is speaking inside you; and the syllables are translated simultaneously into the movement of the color, shade and the light above your head. The walls are singing with moving light, and you are slowly being warmed by some holy fire.

That was the sound of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople. Now, turn westward to the spires of Salisbury, to the Duomo, to Koln, and through one mind's eye, watch:

We walk between walls that bear no weight but rise up and dissolve. We have to resist or be taken captive by vertical radiations in arch and line that begin above us, emanating from the air. Facades become transparencies of colored sunlight. Portals lead inward below successive ribs of molded mastery, drawing us ever farther to the sanctuary and the altar, while growing upward through vast spaces.

And no matter how you try to remain earthbound, the building carries you upward by a simple stratagem: like you, it is part of solid ground, the good earth, but it risesand takes you with itto meet a lofty goal. It is your aspiration, you aspiring, in stone. Your desiring self, not measured against an overbearing skyscraper height or a mothering mountain breast, but borne aloft. Your gravity made celestial. And you cannot resist, because it is all done at a human rate of speed: starting slowly with the gravamen of prostrate pavements and feet-deep granite walls and hidden, thrusting foundations in dark crypts; then, unnoticeably, picking up speed with quickening inner details. And, finally, all of the structureand all inside you, desire, awe, expectation, instinct, curiosity, fearis gathered up weightlessly, soundlessly spiraling heavenward in a breakneck, never-turning-back bid at the skies above our world.

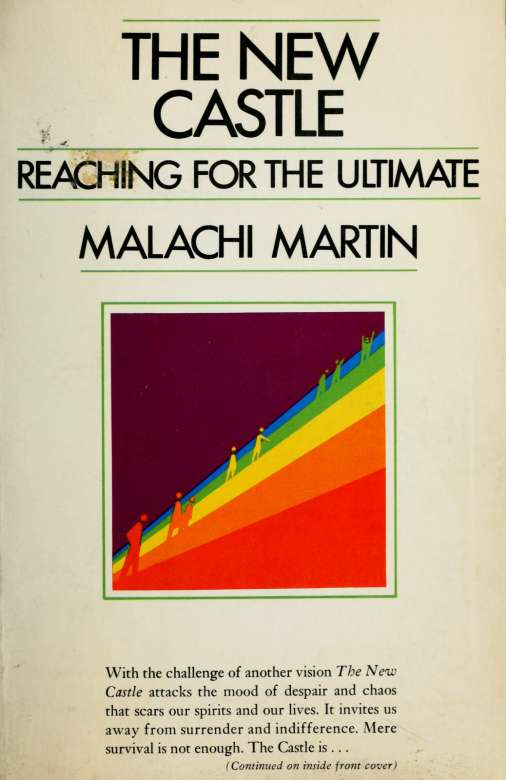

The voice, the eye, the vision are all one man's. Mala-chi Martin is remarkable. Take a Celt, a Dublin Celt at that, breed and rear him in the wet mists and fleeting sun of his mysterious native isle, transplant him to the Jesuit enclaves of the Holy City and imbue him with Roman metaphysic, and language, season him for long years under the Italian and other alien suns, then lo, remove him to the New World, to the fever of New York, the languors of the Southeast, the quirky balm of California and what have you? Only an odd mixture until you add the man, the mind, the spirit, the vaulting prose. You are moving up, on up to other realms, an ascension to the shores of the empyrean. Now, anything becomes possible, including what has been for a half-millennium impossible, a re-synthesis of the physical and metaphysical, of scientific rationality and the reasons of the spirit.

Malachi Martin belongs to a small but growing group bent on restoring the balance that the West began to lose seven centuries ago when, as he has written earlier, Roger Bacon failed in an effort at persuading the Roman Catholic Church to embrace experimental science. From that terrible rejection came the real schism that has divided the world ever since. With the developing triumph of science, the realm of spirit shrank, slowly, almost imperceptibly at first, and then at an ever-quickening pace from the High Renaissance to the deeps of the twentieth century.

We were enriched beyond human reckoning by the products of the quantifying mind and impoverished, again beyond reckoning, at the same time by what we had lost. Balance was gone, all gone, and we had toppled into a crater of loss and despair to which cartographers of the spirit adapted the name of Kafka.

Only now are we starting the long climb out of the depths of that depression. On our ability to complete the trek depends our survival. If we make it, we will at last have escaped the frustration and defeat of Kafka's The Castle to come within sight and reach of the New Castle.

It is the New Castle that is the goal of this extraordinary book by one of the best minds we have on the subject of heaven or hell on earth. The book, in its quest for a new vision of spirit, a new realization of, as Malachi says, "an opening of the divine onto man's affairs," takes us on a journey that begins in Mecca and carries us on to Jerusalem, Constantinople, Rome, Peking, Angkor Wat, Wittenberg and finally, in rightful order, Peru, Indiana. That journey actually started as an idea for a single article for Intellectual Digest that turned into a plan for nine articles and for a much expanded book. This book.

Agree with him or not, Malachi Martin is exhilarating, a bubbling embodiment of Bergson's elan vital. And since the words here are the man, they have the same quality. To those about to embark on this journey with Malachi, I can say with pleasure: Godspeed. It will be his own kind of anabasis, a march from the coast to the interior, a going up.

Martin Goldman Intellectual Digest New York April 1974

THE NEW CASTLE

I. THE CASTLE

The Castle, as image and expression, is as old as predynastic Egypt and as modern as twentieth-century Europe. Throughout, it has been used to describe human existence on the planet Earth as transformed by a quality which men and women ascribed to something they were sure they instinctively knew, and which time and again they described in terms of spirit. However they defined it ("spirit of man," "the spirit in man," "the spirit of the people"), the Castle for them was a vision in which all the material conditions of human living were invested by "spirit" and thus perfected humanly: time and space no longer as sources or occasions of effort, labor, weight, hindrance, inequality, disease, or death; and their personal lives as set in a dimension of freedom, beauty, light, and love. The Castle was the vision of that ideal state.

In the broad sweep of history, there have been about half a dozen occasionsthe outburst of a great religious movement, the apogee of a great culture fathered by such a movementwhen, it seemed to masses of men and women, the Castle was within human reach. These happenings were centered in particular cities and countries Mecca, Jerusalem, Constantinople, Rome, China, Cambodia, Wittenberg, the United States. And they were seen as human thrusts at that humanly perfect quality of existence on Earth; as ascensions of men, by force of the "spirit," to attain the Castle. Human hope and confidence animated each of these thrusts.