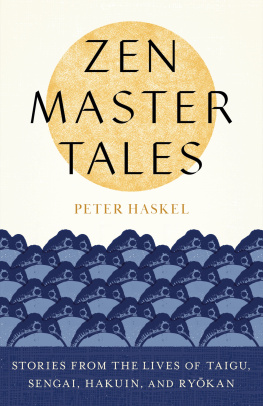

BANKEI ZEN

Translations from the Record of Bankei

Portrait of Bankei, said to be a self-portrait. Property of the Yakushi-in, Kawasaki. (Courtesy Daiz shuppan)

BANKEI ZEN

Translations from the Record of Bankei

by PETER HASKEL

Yoshito Hakeda, Editor

Foreword by Mary Farkas

The author wishes to acknowledge the cooperation of the First Zen Institute of America, New York.

Copyright 1984 by Peter Haskel and Yoshito Hakeda

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of such without the permission of the publisher is prohibited. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the authors rights is appreciated. Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or anthology, should send inquiries to Grove/Atlantic, Inc., 841 Broadway, New York, NY 10003 or permissions@groveatlantic.com.

Published simultaneously in Canada

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bankei, 16221693.

Bankei Zen.

Translated from the Japanese.

1. Zen BuddhismDoctrinesEarly works to 1800.

1. Hakeda, Yoshito S. II. Haskel, Peter, III. Title.

BQ9399.E573E5 1984 294.3927 8381372

eBook ISBN-13: 978-0-8021-9696-5

Grove Press

an imprint of Grove/Atlantic, Inc.

841 Broadway

New York, NY 10003

Distributed by Publishers Group West

www.groveatlantic.com

TO MY TEACHER, YOSHITO HAKEDA, who spoke directly with the masters of long ago and taught me to listen, this book is gratefully dedicated.

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

Frontispiece

Following page

FOREWORD

These days many people travel hundreds or thousands of miles to see or hear Zen masters. Some meet them. Some study with them. Few have a chance to ask them: What shall I do with my anger, jealousy, hate, fear, sorrow, ambition, delusionsall the problems that occupy human minds? And how shall I deal with my work, my mother and father, my children, my husband or wife, my servants, my employersthe relations that make up human life? Can Zen help me?

If the Zen Master Bankei were available for consultation at a nearby street corner today, hed be saying much the same things he did to comfort and enlighten the parade of housewives, merchants, soldiers, officials, monks and thieves who sought guidance from him three centuries ago.

Bankei, the enlightened human being, shares his own experience with us as a real person, speaking his own real words. The advice he gives strikes right to the heart. It is highly personal, not theoretical or abstract. The nature of human beings has changed very little through the centuries, despite numerous efforts to change it. Nor does it seem likely to be less full of passion, jealousy and hate in the next thousand years, here or in outer space.

When Bankei had completed his spiritual training and monastic career, which included the founding of a number of temples and the training of innumerable monks and priests, his true concern was with the problems of ordinary people. He had wanted to share what he had discovered with his mother, his first audience, and, I believe, was finally able to do so before she died, a very old lady. He wants us to have it too.

Peter Haskel has found Bankeis real voice. In this fine work by a young translator who has lived intimately with Bankei for the last ten years and knows him through and through, we are brought smack into Bankeis world. It seems to be no translation at all. Although all the tools of scholarship have been meticulously used, no traces of them mar the polish.

No one needs to explain what Bankei means. His seventeenth-century metaphors and logic can be used or discarded without disturbing the substance of his teaching. What comes through is often just good hard common sense. Except for one thing: the Unborn Buddha Mind. Whether called by this name or any other, it is the heart of Zen as well as the core of Bankeis teaching. Bankeis approach shows that there is no need to be Japanese or imitate the Japanese to appreciate or acquire it.

MARY FARKAS

First Zen Institute of America

New York City, April 1983

PREFACE

My first encounter with Bankei was in the fall of 1972. I had arrived at Columbia University two years earlier, hoping to study the history of Japanese Rinzai Zen, but my general coursework and the extreme difficulties of mastering written Japanese had left me time for little else. Now that I was finally to begin my own research, all that remained was to choose a suitable topic. Brimming with confidence and armed with a list of high-sounding proposals, I went to see my advisor, Professor Yoshito Hakeda. He listened patiently, nodded his head, and then, ignoring all my carefully prepared suggestions, asked me if I had considered working on the seventeenth-century Zen master Bankei. My disappointment must have shown. Although I had never actually read Bankei, I had a vague impression of him as a kind of subversive in the world of Zen, a heretical figure who didnt believe in rules, dispensed with koans and tried to popularize and simplify the deadly serious business of enlightenment. I was hoping to deal with a Zen master closer to the orthodox tradition, I tried to explain, perhaps one of the great teachers of the Middle Ages. Take a look at Bankeis sermons if you have a chance, Professor Hakeda urged, you may find them interesting. My skepticism remained, however, and I did nothing further about Bankei, determined to find a more respectable topic of my own choosing.

The following year, Professor Hakeda raised the subject of Bankei again, and, in spite of my obvious reluctance, pressed on me a small volume of Bankeis sermons. Try reading a few, he said.

Courtesy required that I at least glance over the text, and late that evening I turned to the first sermon and slowly began to read it through. What I found took me completely by surprise. Bankeis approach to Zen was unlike anything I had ever imagined. Here was a living person addressing an audience of actual men and women, speaking to them in plain language about the most intimate, ordinary and persistent human problems. He answered their questions, listened to their stories, offered the most surprising advice. He told them about his own life as wellthe mistakes hed made, the troubles hed had, the people whom hed met. There was something refreshingly original and direct about Bankeis fush zen, his teaching of the Unborn. Here it is, Bankei seemed to say, it really works! I did it, and you can too.

The further I read, the more entranced I became. The next three nights, I could barely sleep. When I returned to Professor Hakedas office, I told him about my experience. You see, he said, laughing, I knew that Bankei was for you!

On my next visit, I arrived with a partial translation of the first sermon and began to read through the text, with Professor Hakeda making comments and corrections as I proceeded. This was the first of many such meetings which continued for nearly ten years and of which this book is the result. The work is, in a real sense, a tribute to Professor Hakeda. Without his assistance, his unfailing patience, wisdom and encouragement, it would never have come into being.

Next page