Shambhala Publications, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Distributed in the United States by Random House, Inc., and in Canada by Random House of Canada Ltd

Guenther, Herbert V.

The Life and Teaching of Naropa.

Reprint, originally published: Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1963. (UNESCO Collection of representative works. Tibetan Series)

Bibliography: p.

Includes indexes.

1. Napda. 2. Buddhist MonksIndiaBiography. 3. Bkargyud-pa LamasIndiaBiography. I. Napda. II. Title.

PREFACE

More than a quarter of a century ago I had the fortune to discover a Tibetan text that I subsequently translated under the title The Life and Teaching of Nropa, and was able to study the ideas it contained under the expert guidance of my teacher and friend, Lama Dam-chos rin-chen, a follower of the Brug-pa (Bhutanese) bka-brgyud-pa tradition, which emphasizes Nropas teaching in all its ramifications. I soon realized that this biography (rnamthar)the Tibetan term describes the manner in which a person grows up spiritually and in this process regains his feedom as an existential experiencewas a unique human document. Because of its rich psychological content, it was eagerly studied by psychologists and many of those who by profession dealt with living persons. The topics discussed in the original text are today as valid as they were at Nropas time, and some of Nropas insights have been reconfirmed by modern cognitive sciences.

There is one other point that makes Nropas life so relevant for modern man. This is the tension between novelty and confirmation. Nropa (originally) stands for the literalist, the reductionist caught in the objectivists fallacy. He has to suffer for his folly until Tilopa, who stands for the visionary and speaks from lived-through experience, enters upon the scene. By pointing out that the images through which psychic life expresses itself are just images, guiding images, not entities to be reduced to and concretized into some banality or another, Tilopa sets Nropa straight and releases him from his self-imposed fetters.

It may be pointed out that only recently it has been suggested that Nropas date may have been about sixty years earlier (9561040) than the date I had calculated (10161100). The arguments for this earlier date pose just as many problems as arguments for the later date, one such problem being the uncertainty about the respective age of the teacher and student when they met. However, if Nropa should have lived as early as suggested, the demise of Buddhism in India as a spiritual movement of its own would have occurred much earliler than hitherto assumed. Already in Nropas teaching there are elements which make his conception of them hardly distinguishable from their Brahmanical interpretation, specifically in the field of psycho-physiological phenomena. Whatever the case may be, the impact of Nropas teaching on the intellectual life of the Tibetans and on their experiential assessing of mans inner life cannot be underestimated, even if in course of time forces within the tradition were at work to reduce his ideas, vibrant with a life of their own, to dogmatic tenets in order to prevent their further development, which might make pet notions obsolete.

The re-issue by Shambhala Publications of a work that in itself has become a classic reflects the publishers awareness, shared by many serious philosophers, that Buddhism as an experiential discipline may play a still larger role in mans life than has hitherto been imagined.

INTRODUCTION

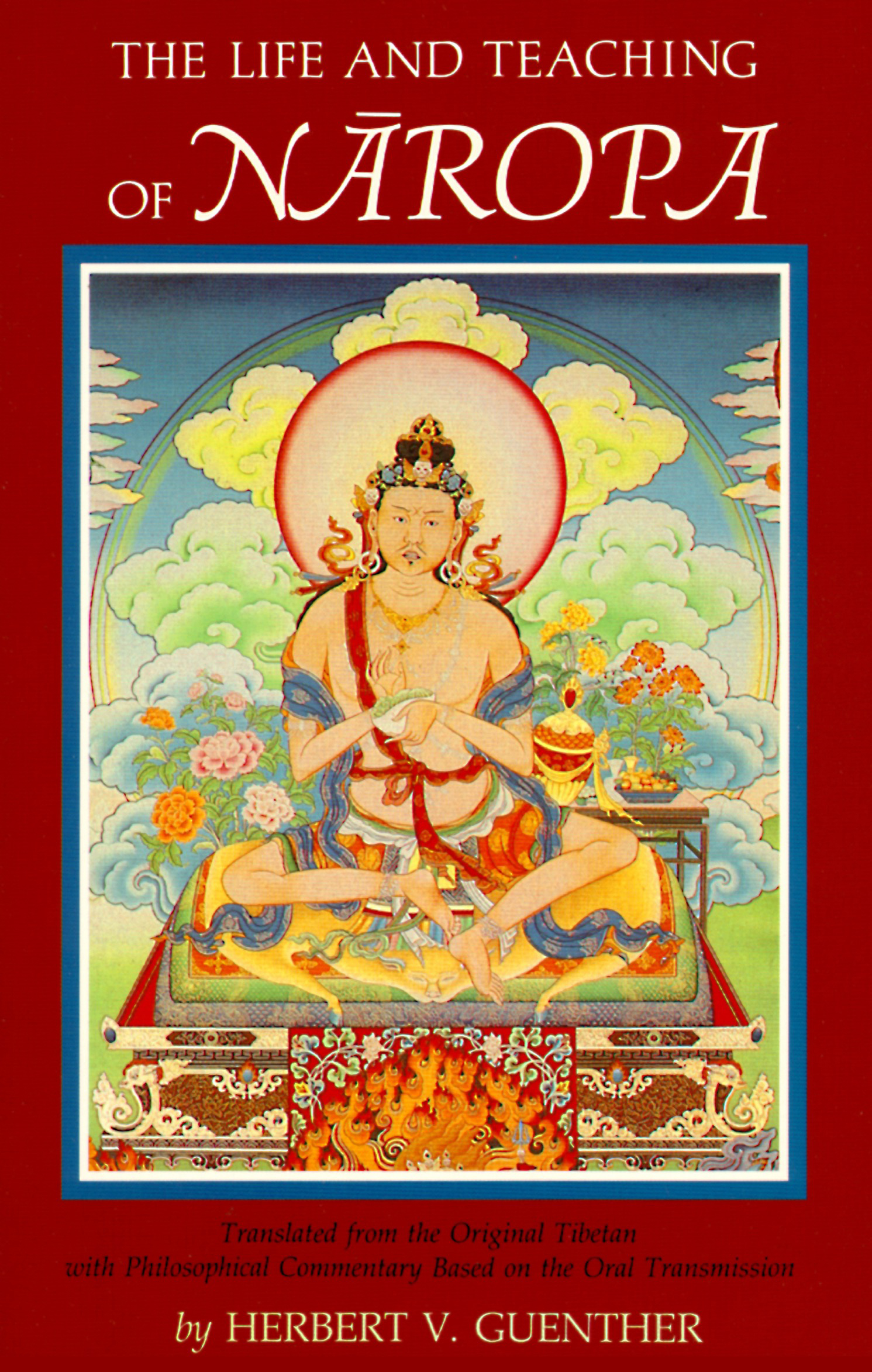

In the history of Tibetan Buddhism the Indian Nropa ( a.d. 10161100) occupies a unique position. To the present day his life is held up as an example to anyone who aspires after spiritual values, which are never realized the easy way but only after years of endless toil and perseverance. It took Nropa twelve years of ardent devotion and indefatigable service to his Guru Tilopa ( a.d. 9881069) to attain his goal: the overwhelming experience of the Real in direct knowledge. Apart from this, Nropa also marks the beginning of a new and rich era of Buddhist thought in Tibet, while at the same time he is the culmination of a long tradition. None of his contemporaries or successors in India can compare with him in depth of experience.

Nropas biography, which has been translated here from hitherto unknown sources, contains a number of strictly historical data, but it is pre-eminently an account of the inner development of this scholar-saint. This makes it of particular interest.

Nropa (Napda, Nroapa) was born in the Fire-Male-Dragon year ( a.d. 1016) in Bengal. He is said to have been of royal parentage, his father being the king i-ba go-cha (ntivarman) and his mother the queen dPal-gyi bio-gros (rmat). Since in ancient-Indian usage the term king is merely an administrative title and does not denote the rank of a European monarch, and since the genealogical tree of his royal ancestry occurs in other combinations in other texts, this designation is merely a long-winded way of pointing out that he belonged to the gentry.

When he had reached the age of eleven ( a.d. 1026) he went for study to Kashmir, at that time the main seat of Buddhist learning. He stayed there for three years and having acquired a solid knowledge of the essential branches of learning he returned home in a.d. 1029. A large number of scholars went with him and for a further three years he continued his studies in their company. But then in a.d. 1032 he was forced to marry. His wife came from a cultured Brahmin family. The marriage lasted for eight years, then it was dissolved by mutual consent. His wife seems to have gone by her caste name Ni-gu-ma, and according to the widely practised habit of calling a female with whom one has had any relation sister she became known as the sister of Nropa.

The vision which induced Nropa to resign from his post and to abandon worldly honours, was that of an old and ugly woman who mercilessly revealed to him his psychological state. Throughout the years he had been engaged in intellectual activities which were essentially analytic and thereby had become oblivious of the fact that the human organ of knowledge is bi-focal. Objective knowledge may be entirely accurate without, however, being entirely important, and only too often it misses the heart of the matter. All that he had neglected and failed to develop was symbolically revealed to him as the vision of an old and ugly woman. She is old because all that the female symbol stands for, the emotionally and passionately moving, is older than the cold rationality of the intellect which itself could not be if it were not supported by feelings and moods which it usually misconceives and misjudges. And she is ugly, because that which she stands for has not been allowed to become alive or only in an undeveloped and distorted manner. Lastly she is a deity because all that is not incorporated in the conscious mental make-up of the individual and appears other- than and more-than himself is, traditionally, spoken of as the divine. Thus he himself is the old, ugly, and divine woman, who in the religious symbolism of the Tantras is the deity rDo-rje phag-mo (Vajravrh) and who in a psychological setting acts as messenger (