I also found a little later

I was growing up fast in those days

that in the old cemetery

among the amputated angels and the listing urns

were ideal places to hide with a girl.

I hid there with Aurelia.

One summer afternoon she and I lay on the bodies

of two knights carved with their arms crossed

on their tombstones

who made a low sorrowful moan of long gone love

until we tumbled between them and there on the broken

debris we commenced the old dance.

Partir cest mourir un peu mais mourir cest partir un peu trop.

VLADIMIR NABOKOV

Its hard times as they say

and Christmas is a dead season.

The wolves have their snouts up constantly

and youll keep home if you know whats good

for you, if you have a home.

Its cold out there; for myself, though, strangely

the desire is greater to break out

of this space I inhabit in loves dungeon,

though the downpour puts a damper on my soul,

and there are a lot of bastards out there.

FRANOIS VILLON, translated by Jean Calais (Stephen Roedefer)

Against Photography

UNLIKE MOST PEOPLE I was not born but snapped and I was not gestated but developed.

Both my parents were photographers. And both of them were Jewish. They were bad Jews because they were photographers. God said, Thou shall not make graven images, and both of them did.

My fathers graven image shop was on the main street in my hometown of Sibiu (or Hermannstadt) in central Transylvania, Romania. My father did all the graduation portraits of the local high schools and technical schools, and also weddings and portraits. The graduating classes posed for group portraits that were then displayed in shop windows up and down the main street. Marrying couples came into the shop directly from City Hall. When I graduated from high school, I refused to wear the school uniform in the class picture. I was the only one out of fifty people who didnt wear a tie. And I insisted that my pseudonym be used under my picture rather than the name I suffered years of school with. My fathers shop was long gone by the time I graduatedas was my fatherbut I was driven. When our portrait was displayed, people remarked: He changed his name, and isnt wearing a tie because hes mad at his father! And my father, in turn, had been mad at God, which is why he made pictures.

My mother and father spent most of the six months that they were married to each other in the darkroom of the photo shop. I was no doubt conceived in the darkroom. And afterwards, I baked there inside my mother under the steady red light for six full months, the time I believe that it takes most major organs and most of the brain to form. My outline must have been there in any case, as well as certain vital shadows. I was then violently wrenched into the light by my parents divorce.

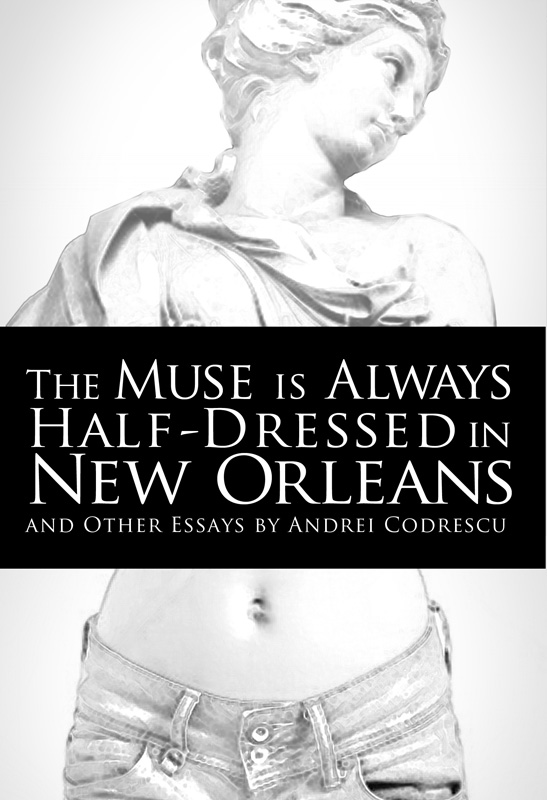

My mother did not get her own photo shop off the ground until two months after I was born. I spent those two months in the sunlight with the family of a policeman while my mother got herself on her feet. These people were pagan. They were sun worshippers who slapped me when I complained about the brightness of the sun. Dont ever say anything like that about the sun again! the policeman warned me. I couldnt wait to get back into the darkroom again. Even today, I live in cities of the night like New Orleans, and dont fully come to life until sundown.

My mothers photo studio was called Baby Photo. (My mothers nickname was Baby, a very chic moniker in Romania where the word was redolent of exotic fragrance, bubble gum, nylons and big bands, a whole jazzy postwar longing that never materialized because the Russians came instead of the Americans.... but thats another story).

Baby Photo was at the very end of the central street by the train station and the clientele wasnt as upscale as my fathers. Mother photographed soldiers and their girlfriends, Gypsies and peasant grandfathers brought in by their families from the countryside to be photographed before they died.

I grew up playing in the shop, and being photographed. I was my mothers favorite subject. She squeezed me into leather spielhosen and velveteen shirts, and had me stand with one leg up on a lace-covered pedestal with my elbow on my raised knee and my head perched sideways on my hand. This elaborate and unnatural position involved the creation of a correct face that my mother coaxed from me by threats, insults, endearments and sometimeswhen it failed to materializeby tears. Dont make that face! shed begin, clicker in hand to the right of the huge camera that dwarfed her, thats an ugly face! You look like a butcher! Dont grin like that! Why do you punish your mother with those rolling eyes! Is this why I was born? So my child can make a face like that?

Amid the laments and the curses my seven-year-old brain raced through the muscles of my face in search of both the appropriate configuration and the most inappropriate because, lets face it, I was delighted by the attention, by the complete critique of any face I chose to invent. I knew the face that looked like a butcher, the mug that broke your mothers heart, the countenance that made her question her existence. It was all there, the ontology and eschatology of mother before the son in search of the photographable mug. At long last, the clicker clicked and I was captured.

Stiff, cramped, in pain, insecure, and exhausted I stand there in the early 1950s looking at a point in the future when I would be released. That point came soon after Stalin died, in 1953, when the whole world behind the Iron Curtain let out a great sigh of relief and everyones face muscles relaxed slightly. Some even smiled. Stalins portrait, which adorned every building and dwarfed every school wall, came down. In its stead, other pictures took up the space. Our mono-pictural black-and-white world gave reluctant way to a serial picture world with hints of color in it. Of course, it wasnt until I left Romania in 1965 that I realized that the world could be multi-imaged and color-explosive, and that people could actually wear unconstrained faces.

Those early fifties photo sessions left me with a permanent terror of cameras. Whenever someone points one at me now I run automatically through a repertoire of faces before I settle on the one I have approximately decided is correct. It doesnt really matter whos behind the camera; there is only one photographer, my mother. And so to the question of somewhat larger import, whos watching? I can truthfully answer, my mother, and I believe that this is the case for most people whether their mother was a photographer or not. Mothers watch. And, as John Ashbery put it in a poem: All things are tragic when a mother watches. There is also only one photograph: Stalins, and that is the other story. My mother may have photographed me but the end product was a picture of Stalin. In those days, Stalin was everything. If you asked a schoolchild what two plus two were, he answered: Stalin. Likewise, if you handed someone a picture of their recently departed grandmother and asked who they were seeing, they said: Stalin. There was no one else. Given the elementary authority of that world, as well as certain subsequent developments, I can never believe that photography is in any way objective. The photographer, who is the watcher, is always the parent, the subject is always the child, and the end result is always Stalin. And Stalin resembles the photographer more than he resembles the child. The child, like nature, is only there to be used by authority, machines and the authority of the machine. And this result, this photograph of Stalin, is always tragic.