Project website:

http://www.al-mutanabbistreetstartshere-boston.com/

Jaffe Center for Book Arts:

http://www.library.fau.edu/depts/spc/JaffeCenter/collection/al-mutanabbi/index.php

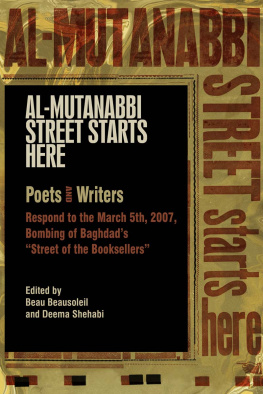

Al-Mutanabbi Street Starts Here

Edited by Beau Beausoleil & Deema K. Shehabi

2012 PM Press

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be transmitted by any means without permission in writing from the publisher.

ISBN: 978-1-60486-590-5

Library of Congress Control Number: 2011939672

Cover designed by Tania Baban, based on a broadside printed by Suzanne Vilmain for the Al-Mutanabbi Street Broadside Project

Interior design by briandesign

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

PM Press

PO Box 23912

Oakland, CA 94623

www.pmpress.org

Printed in the USA on recycled paper, by the Employee Owners of ThomsonShore in Dexter, Michigan.

www.thomsonshore.com

Contents

Introduction

Sometimes the weight of our own silence becomes completely unbearable, until we cannot take one more day of reading about the blood, bone, and ash.

And then the moment comes when we recognize that this distant landscape is our own, and that we must walk through it.

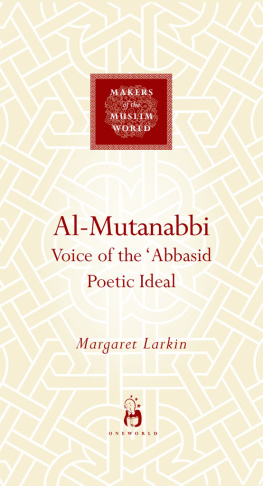

On March 5, 2007, a car bomb was exploded on al-Mutanabbi Street in Baghdad. More than thirty people were killed and more than a hundred were wounded. This locale is the historic center of Baghdad bookselling, a winding street filled with bookstores and outdoor book stalls. Named after the famed tenth-century classical Arab poet, al-Mutanabbi, this is an old and established street for bookselling and has been for hundreds of years. It has been the heart and soul of the Baghdad literary and intellectual community.

The connection between the booksellers and readers on al-Mutanabbi Street and the booksellers and readers here is very simple and direct. We all share the belief that books are the holders of memories, dreams, and ideas. I felt, as a poet and bookseller here in San Francisco, an urgent need to keep this singular, tragic event in our consciousness, because it has such deep historical and cultural implications, for us, here in this country, and for the people of Iraq. To this end, I decided to create a coalition of poets, artists, writers, printers, booksellers, and readers.

I had two basic goals. The first goal was to have those involved in the arts respond to this targeted attack. A response that would consider the various underpinnings that made up the fabric of al-Mutanabbi Street: a street that held bookstores, a street that held both Shia and Sunni, a street that indeed welcomed all Iraqis, a street where people felt relatively safe as they walked, browsed books, bought stationery, arranged for printing, or sat in the Shabandar Cafe. These same people somehow believed that this place of knowledge and history protected them from the encroaching chaos.

Besides seeking to gather more dead, the car bomber and his cohorts were attacking the thoughts and ideas latent in each book, trying to also kill the notion that someone might be free to say something not sanctioned by them. It didnt matter if that idea was in a childrens book, a book of philosophy, a memoir, poetry, or perhaps even more dangerous, a blank notebook.

My second goal was to try to close the distance between al-Mutanabbi Street and similar cultural streets here and around the globe. I want people to understand the commonality that exists between al-Mutanabbi Street and any street that holds a bookstore or a cultural institution. I want people to understand that a carefully chosen attack like this should be seen as an attack on us all.

I have felt that concentrating our attention on this one car bombing, on this one day, on this one narrow winding street, would reveal many things to us and perhaps also help us to see the bond we have with everyday Iraqis. These are the Iraqis who get up each day and work to live, Iraqis whose lives are altered forever by being in the wrong place at the wrong time: while on their way to work, to school, to the market, just sitting in a cafe, or picking up a book to read on al-Mutanabbi Street.

I have come to feel that wherever someone gathers their thoughts to write towards the truth, or where someone sits down and opens a book to read, it is there that al-Mutananabbi Street starts.

As much as this anthology celebrates al-Mutanabbi Street and helps others understand what it means to the Iraqi cultural community, it is also a lament for those who were killed and wounded that day, and by extension, on all the streets and days before, and days after, even this very day, as I write these words.

Al-Mutanabbi Street has reopened, although many booksellers were killed, and many of the survivors left the street; still books are being displayed and sold again, and the gutted Shabandar Cafe has been made new (the owner lost many family members in the blast). And, today my friend Maysoon Pachachi writes to me, We will see how long it will take for al-Mutanabbi Street to get its soul back.

One might say the same about our own country, as well.

I have always wanted the Iraqi cultural community to know that we would not let them endure all that has happened in silence. Al-Mutanabbi Street starts in many places around the globe. Everywhere it starts it seeks to include the free exchange of ideas. We must safeguard that.

These are our words.

Al-Mutanabbi Street starts here.

Beau Beausoleil

Preface

Al-Mutanabbi Street in Baghdad:

When Books Take You Captive

Muhsin al-Musawi

When writing or speaking of al-Mutanabbi Street, one cannot make a mere reference to a street in an urban center, not only because it has long been recognized as the consortium par excellence for booksellers, scribes, and bookstores in Iraq, but also because of its long history. Al-Mutanabbi Streets lineage dates back to the urban district of scribes of Abbasid in Baghdad (762-1258 CE), and it challenges our knowledge of the genealogy of culture and the resilience of an industry that has been resisting destruction. Samuel Kramers monumental study of Sumerian and old Mesopotamian writing, as the oldest and earliest in the world, consolidates an Iraqi tradition which is as much a celebration of writing as of fertility and love. However, this celebration is always challenged and confronted with powers of destruction and death. In Sumerian poetry war and destruction were metonymized as storms, callous, devastating and ignorant. In Kramers eloquent translations of poetic tablets, we are met with the impetus of passionate narratives and pleadings anchored in a sublime human yearning for peace and a life of plenty. Writing itself is a celebration of this will to live, for only through recuperation, reproduction, fertility, and love can a human society survive in joy.

Mesopotamian writing is a testimony to this longing and struggle. Although Baghdad is new in comparison to these ancient traditions, it inherited this love for writing and documentation upon its establishment in 762 CE, and sustained it through the citys cultural growth. The area around al-Mutanabbi Street itself was the old Abbasid district of scribes markets and booksellers stalls and shops. At that time it was probably adjacent to Darb Zakha, or Zakha Alley, where there were then cultural and educational institutions and schools. It was part of a large and thriving district of many alleys that were usually referred to as Suq al-Warraqin (Scribes Markets). The renowned bibliophile al-Nadim (died 998 CE) made eloquent mention of this market, which Ahmad Ibn Tahir, the celebrated Ibn Tayfur (died 893 CE) had already documented in his book on the history of Baghdad. The jurist Ibn al-Jawzi (1200 CE) would write later his book Manqib Baghdad (Baghdad

Next page