I BURNED FOR YOUR PEACE

PETER J. KREEFT

I BURNED FOR YOUR PEACE

Augustines Confessions Unpacked

IGNATIUS PRESS SAN FRANCISCO

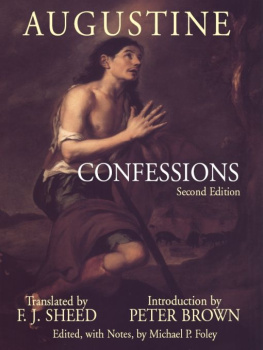

Cover design by Enrique Aguilar

2016 by Ignatius Press, San Francisco

All rights reserved

ISBN 978-1-62164-040-0 (PB)

ISBN 978-1-68149-712-9 (EB)

Library of Congress Control Number 2015948592

Printed in the United States of America

CONTENTS

Introduction to This Book

A book about another book? Yes, for this other book is only the most beloved book in the world, next to the Bible. But why does it quote only snippets, only parts of the Confessions , in fact less than 10 percent of the text? Because a commentary on the whole book would be much too long. And also because we remember only snippets, we cherish only the big ideas. To hammer those few big nails deeper into our minds is much more memorable than to tap gently at every page.

So this book is not a complete scholarly commentary on the Confessions . It is not complete, it is not scholarly, and it is not even a commentary in the usual sense of the word. It is an unpacking of some of the riches in Augustines massive treasure chest. It is a string of pearls obtained by diving expeditions into the oyster beds in the deep sea of the Confessions . It is a festooning of some of the branches of the gigantic Christmas tree Augustine grew. It is a framing of some of the masterpieces of art in Augustines studio. My words are only the unpacking, the stringing, the festooning, the framing. They set off and call attention to Augustines words (printed in boldface type), as his words do the same thing to the Word, Christ. The reader must practice sign reading: look not at signs, but along them, at what they point to: look along my words to Augustines and along his to Christ.

Here is the best way to read this book. (1) First, read each boldface-type quotation from Augustine. (2) Next, do not rush on to my commentary, but think about what Augustine said. (3) Then read what I say about it. (4) Then go back to the Augustine quote and read it in that light. Of these four stages, only one (no. 3) is from my mind. One is from yours (no. 2), and two are from Augustines. That is the right proportion.

Introduction to Augustine

You have never met a man like Augustine. For there has never been another man like Augustine.

Medieval statues of him have many different faces but always the same two symbols: a burning heart in one hand and an open book (the Bible) in the other. For Augustine combined fire and light, a passionately fiery heart and a dazzlingly brilliant head, as no mere man in history has ever done. Saint Paul, Pascal, Dostoyevsky, Nietzsche, and Kierkegaard are the only ones I can think of who come close.

Every person now alive would be a different person, or would not be at all, if Augustine had not lived. Almost single-handedly he forged the medieval mind. Yet he is also quintessentially modern: introspective, emotional, self-doubting, complex.

He is also the major bridge between Catholics and Protestants. No other writer outside the Bible is so deeply loved and claimed by both sides. He is a man for all sides, all sects, and all sexes. (Most of the lovers of Aquinas are men; half the lovers of Augustine are women.)

He lived (A.D. 354430) during the troubled transition time that marked the end of one era and the beginning of another: between ancient and medieval, classical and Biblical, pagan and Christian, Roman and barbarian. He lived through the Fall of Rome (A.D. 410) and died as the smoke and fires of the barbarians were burning Thagaste, his home, his native city in Africa, twenty years after Rome fell. Rome was not just a city; it was the eternal city. Rome was the empire, Rome was the West, Rome was civilization itself. The equivalent of a nuclear winter, a five-hundred-year-long dark ages, was beginning.

To this cosmic crisis Augustine responded with one of the most powerful and radical deeds a human being can do: he wrote a book. Many books, actually, but especially two of the greatest books ever written.

One of them, the 1500-page-long City of God , is the worlds first philosophy of history. It interprets the Fall of Rome by putting it into the largest of perspectives, surrounding it with the greatest of frames: the story of everything, the whole history of the world from the Creation to the Last Judgment. And this, in turn, is surrounded by an even greater frame: divine Providence, the eternal Mind of God, as revealed first in Sacred Scripture and then, in light of that light, in history. (For in your light do we see light.)

Both collectively and individually, the theme of human history is revealed as the central theme of every story: the conflict between Good and Evil, between light and darkness, between Christ and Antichrist, between Thy will be done and my will be done. Augustines terms for the collective entities that embody those two choices are the City of God and the City of the World ( Civitas Dei and Civitas Mundi ).

We are what we love. Two loves have made two cities, he says: the love of God to the refusing of self has made the City of God; the love of self to the refusing of God has made the City of the World. The City of God is the invisible but real community of all those who love God as God. The City of the World is the invisible community, or non-community, of all those who love themselves or the world as their God.

(World here, as in Scripture, means, not the planet, which the good God made, but the world order, the historical era that fallen man made by the Fall; it is a time-word, not a space-word.)

The City of God is a co-inherence, a true community, i.e., a common-unity. It is a diversity of individuals, races, and cultures united by its common love of the one God, which love is both for the one God as its one ultimate end and from the one God as its one ultimate origin. The City of the World is not a co-inherence but an incoherence; it is not really a community, because it worships many gods.

This polytheism is not dead today but very much alive. The fact that we no longer worship the pagan Roman gods does not mean that we are not polytheists. In fact, we are more polytheistic, not less: we have as many gods as there are worshippers.

Introduction to the Confessions

This drama of history, this spiritual warfare, is played out socially, publicly, visibly, and collectively in The City of God and individually in the Confessions . It is the same drama.

Two dimensions of this drama are Gods providential design and mans free choices, or predestination and free will, or destiny and responsibility, both of which Augustine strongly defended. For he saw them, not as contradictory, but as complementary dimensions of the dramalike the two dimensions of every smaller story ever told by anyone in this Great Story: the predestination and providence of its Author and the real choices of His characters. One author could conceivably destroy or diminish a rival authors free will (e.g., by murder or a lawsuit), and one character can do the same to another character, but the author and his characters are not rivals. Therefore, predestination and free will are not rivals.

We make free choices first of all with our heart. The heart is the faculty by which we love. Thus two loves have made two cities. Amor meus, pondus meum , Augustine says: My love is my weight, my gravity, my density, and therefore my destiny. I go where my love goes. To live is to love, and to love is to choose one fork in lifes road rather than the other, and that choice creates your destiny. Eastbound roads simply cannot take you west, or vice versa; and Hell-bound roads simply cannot take you to Heaven, or vice versa.

This drama is the content of time. Its end is eternity. Nothing can be more dramatic than that. The City of God is that drama collectively, publicly, and externally; the Confessions is the same drama individually, privately, and inwardly.

Next page