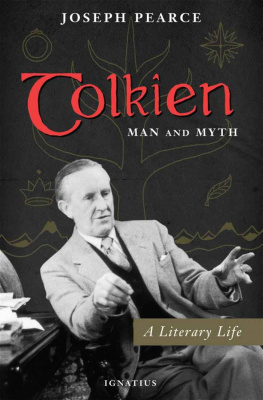

Copyright 2015 Joseph Pearce.

All rights reserved. With the exception of short excerpts used in articles and critical review, no part of this work may be reproduced, transmitted, or stored in any form whatsoever, printed or electronic, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Cover design by Caroline Kiser.

Cover image by Eric Edwards.

Cataloging-in-Publication data on file with the Library of Congress.

A F UNDAMENTALLY R ELIGIOUS AND C ATHOLIC W ORK

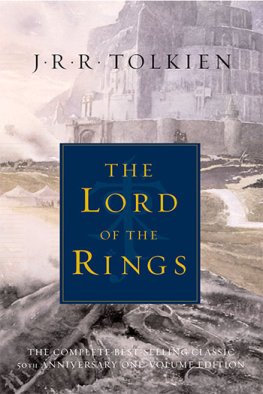

The Lord of the Rings is of course a fundamentally religious and Catholic work; unconsciously so at first, but consciously in the revision. That is why I have not put in, or have cut out, practically all references to anything like religion, to cults or practices, in the imaginary world. For the religious element is absorbed into the story and the symbolism.

J. R. R. Tolkien to Robert Murray, S.J.

As for any inner meaning or message, it has in the intention of the author none. It is neither allegorical nor topical.... I cordially dislike allegory in all its manifestations, and always have done so since I grew old and wary enough to detect its presence.

J. R. R. Tolkien

T here is a mystery at the heart of The Lord of the Rings that continues to baffle and confuse the critics. Is it a fundamentally religious and Catholic work, as Tolkien claimed in a letter to his Jesuit friend, Father Robert Murray, in December 1953, or is it, as he claimed in the foreword to the second edition of The Lord of the Rings, devoid of any intentional meaning or message? If Tolkien dislikes allegory in all its manifestations and if he insists that it is neither allegorical nor topical, how can it be Catholic? If there is no literal reference to Christ or the Church and no allegorical level of meaning, the work cannot be Catholic. Its as simple as that. And yet it cant be as simple as that because Tolkien also insists that it is religious and Catholic, prefixing the assertion with of course, as if to state that the religious and Catholic dimension is obvious.

The mystery deepens when we realize that Tolkien refers to The Lord of the Rings on another occasion as being an allegory. Replying to a letter in which he was asked whether The Lord of the Rings was an allegory of atomic power, he replied that it was not an allegory of Atomic power, but of Power (exerted for Domination). Having confessed the allegory of power, he asserted that this was not the most important allegory in the story: I do not think that even Power or Domination is the real center of my story.... The real theme for me is about something much more permanent and difficult: Death and Immortality.

It seems, therefore, that Tolkien contradicts himself, describing his work as an allegory in one place and denying that it is an allegory in another. Is he confused, or is he simply guilty of employing the same word to denote two different things? Is The Lord of the Rings an allegory in one sense of the word and not an allegory in another?

Clearly Tolkien is not confused about the meaning of allegory. He was a philologist and professor of language and literature at Oxford University. As such, we can safely assume that he is using the word allegory in two distinct senses. In one sense, The Lord of the Rings is an allegory; in another sense, it is not.

Perhaps, at this juncture, it would be helpful if we took a moment to discuss the various meanings of allegory. Linguistically, allegory derives from the Greek word allegoria, itself a combination of two Greek words: allos, meaning other, and agoria, meaning speaking. At its most basic level, therefore, an allegory is anything that speaks of another thing. In this sense, every word we use is an allegory. A word is a label that signifies a thing. A word, if spoken, is a noise that points our minds eye to the thing the noise signifies; if written, it is a series of shapes that point our minds eye to the thing the series of shapes signify. It is indeed astonishing to realize that we cannot even think a single thought without the use of allegory, a mysterious fact that subjects all perceptions of reality to the level of metaphysics, whereby the literalness of matter is always transcended by the allegory of meaning.

It is clear that Tolkien could not have had this basic meaning of allegory in mind. At this level of understanding, The Lord of the Rings is obviously an allegory because it couldnt possibly be anything else. This being so, lets continue with our exploration of the different types of allegory so that we can discover what sort of allegory The Lord of the Rings is and what sort of allegory it isnt.

The most elevated form of allegory, or at least the most sanctified, is the parable. This is the form adopted by Christ to convey the truth He wished to teach. The prodigal son did not exist in reality; he was a figment of Christs imagination. Yet the story of the prodigal son has a timeless applicability because we can all see something of ourselves and others in the actions of the protagonist and perhaps also in the actions of the forgiving father and the envious brother. Insofar as the parable reminds us of ourselves or others, it is an allegory. Insofar as Frodo or Sam or Boromir remind us of ourselves or others, The Lord of the Rings is an allegory.

A far less subtle type of allegory is the formal, or crude, allegory, in which the characters are not persons but personified abstractions. They do not have personalities but merely exist as cardboard cutouts signifying an idea. For instance, Lady Philosophy in Boethiuss The Consolation of Philosophy is not a person but a personified abstraction. She exists purely and simply to signify the beauty and wisdom of philosophy. Similarly, the character Christian in John Bunyans The Pilgrims Progress is not a person but a personified abstraction who exists purely and simply to signify the Christian believer on his journey from worldliness to otherworldliness. As a formal allegory, every character in Bunyans story is a personified abstraction. C. S. Lewis echoes Bunyans method in The Pilgrims Regress by introducing characters such as a beautiful maiden in shining armor called Reason who has two beautiful younger sisters called Theology and Philosophy.

Tolkien is evidently referring to this kind of allegory in the foreword to the second edition of The Lord of the Rings. He cordially disliked such allegories because they enslaved the imaginative freedom of the reader to the didactic intentions of the author. In order to teach and preach, the author of a formal, or crude, allegory dominates the readers imagination, forcing the reader to see his point. Whereas good stories bring people to goodness and truth through the power of beauty, formal allegories shackle the beautiful so that goodness and truth become inescapable. Such allegories may have the good and noble purpose of teaching or preaching, but they do so at the expense of the power and glory of the imaginative and creative relationship between a good author and his readers.